Chapter 3

How does intermittent fasting work?

If you’re wondering about the science behind intermittent fasting, this chapter breaks down what happens in your body (and when) during the fasting process. We’ll also cover intermittent fasting’s impact on metabolism and appetite, and what research says overall about whether intermittent fasting is healthy.

Key concepts

- Knowing the science of fasting is useful. Once you understand how intermittent fasting works, you’ll be able to weigh the pros and cons for yourself (or help your clients do the same).

- “Fasted” is a metabolic state that the body enters after 8-12 hours without food. It’s defined by the shift in nutrient use from “external” to “internal” sources. This shift is what creates the biochemical changes—and potential benefits—of fasting.

- Intermittent fasting can be healthy for some people. But there’s a sweet spot. Fast too intensely, and the benefits fade.

It all sounds a bit magical.

According to intermittent fasting (IF) proponents, people can experience a range of health benefits just by doing one simple thing: changing when they eat.

For anyone who’s struggled to consistently stick to a regimented diet, not worrying about what to eat—or even how to eat—can certainly sound heavenly.

Still, if you’re going to go a long time without food, you kinda want to know that your efforts will pay off.

Does IF actually work? If so, why? And for whom?

In this chapter, we’ll attempt to answer those questions.

We’ll dive into the science of everything IF, shedding light on:

- How IF works

- Why fasting might be healthier than eating more frequently, at least for some people

- What fasting does and doesn’t do to your metabolism

- Why fasting may not make you as hungry as you think

Let’s start with the top question most people have:

How does intermittent fasting work?

Let’s take a look at what happens in the body when you go more than 8 hours without food.

We’ll start with the last meal consumed.

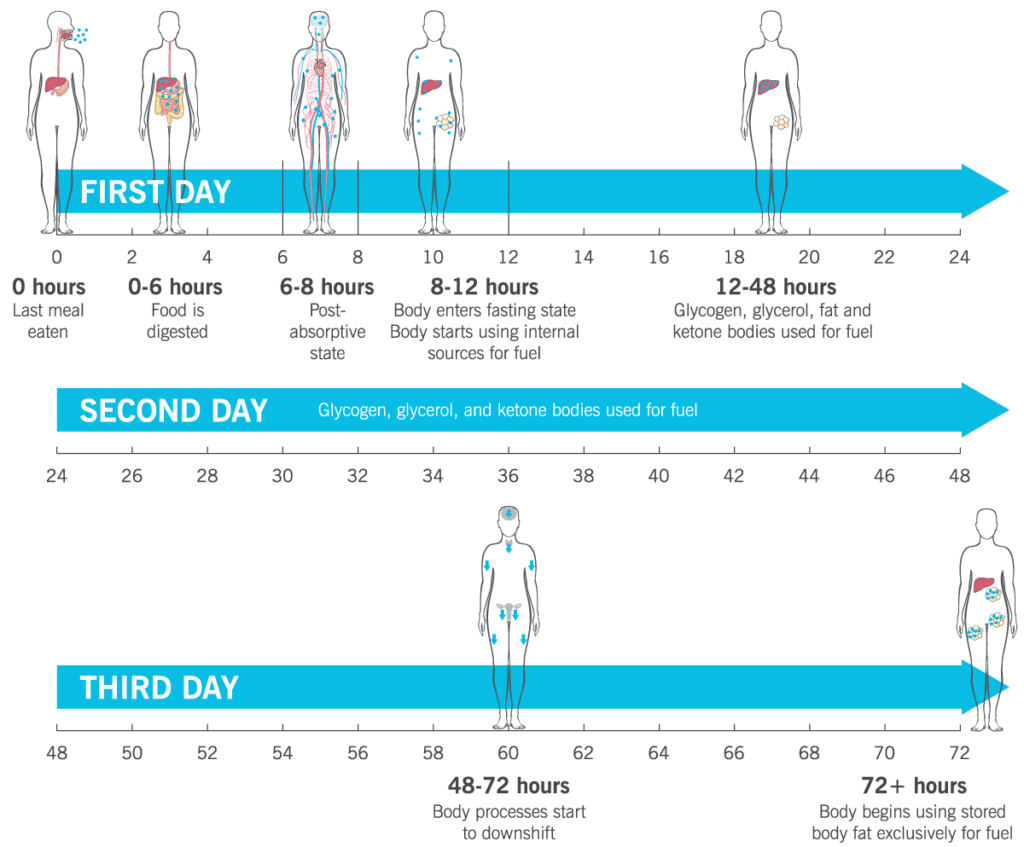

- 0 hours: You eat.

- 0-6 hours: As your body digests and absorbs your meal, hormones (chemical messengers in the body) and neuropeptides (chemical signals in the brain) are released, helping to move nutrients into cells and tell you, “Hey there, you’ve eaten enough. Go ahead and put your plate in the dishwasher and move on to other activities.”

- 6-8 hours: Most if not all of your meal has been digested. Now you’re in what’s called the post-absorptive state. Nutrients from the meal are available for your cells to use for energy, repair, or other jobs.

- 8-12 hours: Your body has largely cleared and used all the nutrients from your last meal. This shift in energy and nutrient use from “outside sources” (a meal) to “inside sources” (what’s stored in your body) creates the biochemical changes that define the fasted state.

- 12-48 hours: Your liver releases ketone bodies as well as stored glycogen, and your liver and kidneys start making glycerol and free fatty acids. These are all substances your body can use as fuel. (You can read more about this process in this article about the ketogenic diet.)

- 48-72 hours: If you’re in the fasted state longer than a couple of days, your body starts to slow or change key physiological processes (more about this below) in order to keep you alive.

- 72+ hours: By about two to three days into a fast, you’re almost completely dependent on fatty acids released from your adipose (fat) tissue for fuel. In long-term starvation conditions, this helps spare your more valuable stash of protein, which makes up most important body structures, such as your internal organs.

Is intermittent fasting healthy?

The benefits of fasting largely stem from calorie restriction. When you fast, you obviously eat less (or nothing).

Fasting also stimulates many cellular and molecular mechanisms that our bodies use to thrive in conditions of food scarcity. Blood sugar, insulin, resting heart rate, and blood pressure all decrease—while insulin sensitivity and cell clean out (called autophagy) improves. Those are all positive signs.

But the IF story isn’t 100 percent good news.

Intermittent fasting and women

While intermittent fasting seems to benefit males, it can have a negative effect on hormones and metabolism in some females.

Turns out, the hormones regulating key functions—like ovulation, metabolism, and even mood—are incredibly sensitive to your energy intake.

In fact, changing how much—and even when—you eat can mess with reproductive hormones. This can lead to a far-reaching ripple effect, causing all sorts of health issues.

(Read more: Does intermittent fasting work for women?)

Will intermittent fasting break your metabolism?

One of the biggest objections to the concept of IF is the idea that people should eat frequently to “boost their metabolism.” But there are a couple problems with that theory.

Problem #1: The “metabolism-boosting” effects of frequent eating are overrated, especially for losing fat, research suggests.

A number of years ago, some nutrition experts thought frequent meals would help folks boost metabolism through something called the thermic effect of food (TEF).

TEF is the energy used to digest, absorb, and utilize the nutrients from your food. The theory was that by eating more often, you were stimulating TEF more often.

We’ve since learned, however, that the number of meals doesn’t matter. TEF is stimulated equally whether you eat three 600 Calorie meals of six 300 Calorie meals.1,2,3

Problem #2: There’s a difference between fasting and starving.

Check out the definitions below.

- Fasting: Going without food long enough (usually 8-48 hours) to trigger the body to dip into stored energy.

- Starving: A state of extreme nutrient and energy deprivation that can potentially kill us.

The difference between the two one of the key reasons IF probably won’t mess with your metabolism.

Of course, you want to fast long enough to see benefits, but not so long that your body and brain start to think you’re in trouble.

So the question is: How long can you remain in that fasted state before things go horribly wrong? The answer depends on your individual physiology. For most people, fasting one day a week offers benefits without many risks. It’s the same with 5:2 eating and 16:8 fasting.

Fasting twice a week or every other day? It can work for some people—but creates problems for others. (You’ll learn more about how to tell the difference in chapter 8).

Will intermittent fasting make you ridiculously hungry?

Maybe not.

To explain why, we’d like to tell you about a one-day experiment we suggest to our coaching clients: Fast for 24 hours.

Oh, do people fear this experiment. They worry so much about how horrible it will be.

But by the end of the 24 hours?

They tell us things like, “You know, it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be. I thought I would be a lot hungrier.”

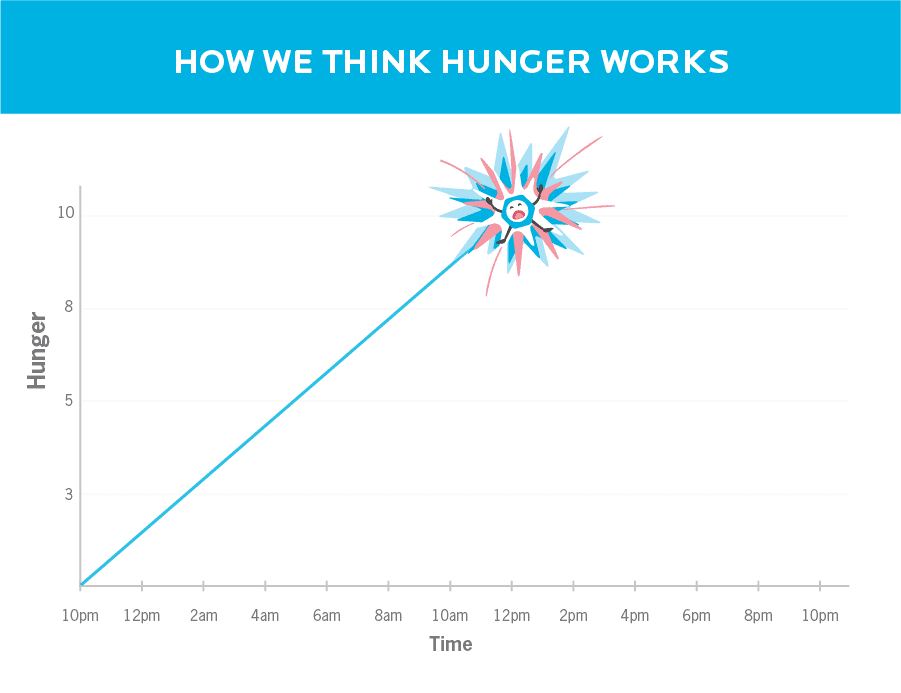

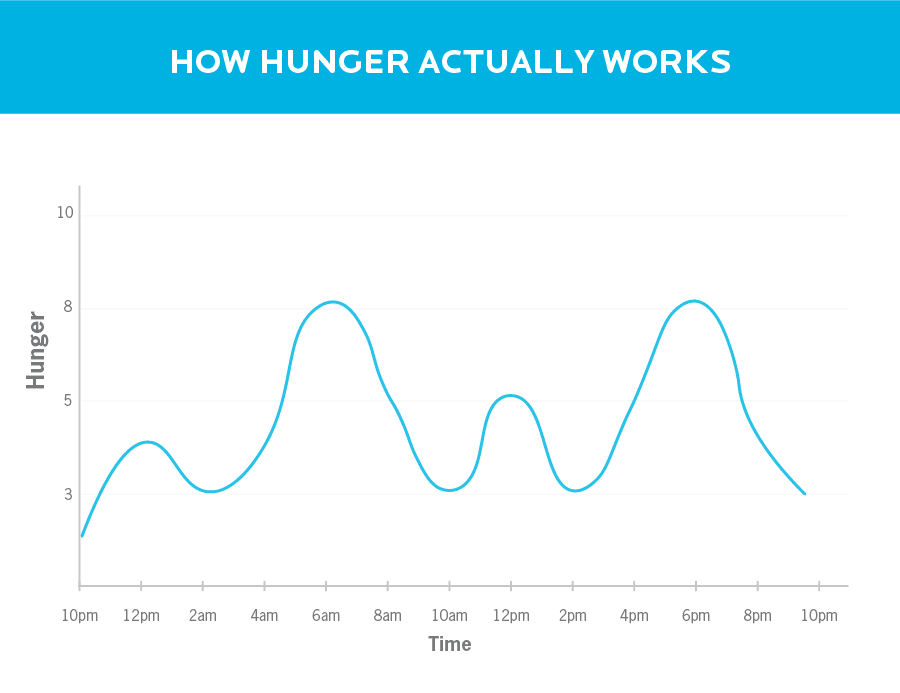

There’s a scientific reason for this. Hunger hormones are released in waves based on when our bodies expect us to eat, which is usually after about five hours of not eating.4

But if you don’t eat at that time, the wave of hunger will diminish, until the body thinks it’s time to eat again.

You know that hungry feeling you get about four or five hours after your last meal? Where your stomach’s rumbling to remind you that it’s been a while?

Hunger peaks at that point—and immediately diminishes.

After a while, even if you haven’t eaten, you get less hungry.

About 20-24 hours later, hunger comes back again. But never as bad.

End result: Fasting doesn’t generally make you feel as hungry as you might expect.

Bottom line: Fasting does work.

When it comes to fasting, there’s a sweet spot. We’ll tell you more about what that looks like in the coming chapters. For now, just know this: Fast too intensely or for too long? Folks fall apart.

Get it just right, however, and people can experience a wide range of benefits, ranging from improved fat loss to better health.

In the next chapter, we’ll explore those benefits in depth.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.