Contrary to recent headlines, aerobic exercise alone is not a recipe for faster fat loss.

Instead, a combination of resistance training and aerobics will lead to the most impressive, and longest lasting improvements in body composition.

Introduction

Back in December, PN’s Dr. John Berardi posted a link on his Facebook page to an article on Science Daily, with the headline:

“Aerobic Exercise Trumps Resistance Training for Weight and Fat Loss”

This post led to much controversy and outraged discussion. Why?

Where to begin?

First, Science Daily’s headline misrepresents the study’s results. The study doesn’t actually conclude that aerobic exercise is better than resistance training for weight or fat loss.

Huh? Then what’s up with that headline?

Well, first – as usual – the media oversimplified things; to the point of not even being accurate. And yes, that’s why most media headlines are not very trustworthy.

Second, the study used terrible training programs. Both the aerobic training program and the resistance-training program were less than optimal. Way less than optimal.

Of course, it’s pretty difficult to draw reliable conclusions about the relative effectiveness of exercise programs that are ineffective in the first place!

Third, this study included no nutritional intervention.

Why is this a problem? Here’s an explanation from JB himself: “Why exercise STILL doesn’t work.”

Finally, researchers in this study didn’t seem too concerned about the difference between fat loss and lean mass loss. They lumped it all together as “weight loss”, as though there really wasn’t a difference between a pound of muscle and a pound of fat.

Muscle mass matters. A lot.

Do you like walking up stairs on your own or would you rather take one of those home stair lifts? Have you seen one of these things?

First you have to wait for the lift to ever-so-slowly make its way down the stairs. Then you get in it and slowly go up the stairs.

I tried it once with my pet turtle Herb. Herb jumped off half way up. He didn’t have the patience and decided to walk up the stairs.

On a more serious note: For a while, I researched treatments for muscular dystrophy, a disease that causes severe muscle loss. Do that kind of research for a day or two, or talk to people with muscular dystrophy, and you’ll quickly recognize the vital importance of maintaining muscle, even if your goal is to lose weight.

My biggest peeve in the weight loss industry is that weight loss is the measurement for success. For example, here are some other ways to lose weight:

- Amputation.

- Osteoporosis.

- Stomach flu (though intestinal parasites will do in a pinch).

- Coma.

- Chemotherapy.

- Shaving all your hair off.

- Lobotomy.

Thanks, but I’ll pass on all of those.

Muscle helps you walk up and down stairs and pick up a soup can. And, of course, keeping you moving is muscle’s most important function.

But muscle can also help you lose fat and stay lean.

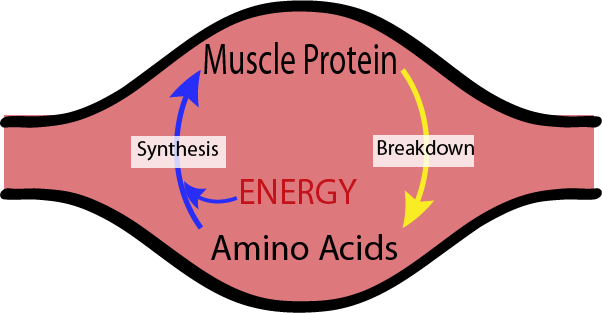

Muscle metabolism

Increased basal metabolism is probably the most obvious advantage of having more muscle. Actually, to be more exact, the more muscle you carry, the higher your resting energy expenditure (REE).

Since REE is the biggest part of your total energy use in a given day, it can change how many calories you burn [1] .

Have you ever wondered why muscle uses energy when you’re doing absolutely nothing? Seems like a waste.

Well, muscle is always up to something. It’s constantly being broken down and re-constructed, or synthesized. In fact, all tissues, to one degree or another, are constantly being remade. It takes about seven days to completely regenerate your skin, and seven years to replace every cell in your skeleton [2].

What makes muscle special is that you can make more of it – a lot more. In other words, unlike bone and skin cells, muscle generation is, to some extent, within your control. Whereas after puberty, you can’t make a lot more of other tissue. Except fat.

Muscle: by the numbers

Your body uses energy to break down and remake muscle. How much energy? That depends on how much muscle you have.

If you really want to know how much energy muscle uses, take a look at the calculations below.

(In case you have deep-seated math phobia, here is the lowdown: Each kilogram of muscle uses at least 10 kcal per day [3]).

Okay with that? Then skip to the next section. Fellow math nerds can read on for the more detailed explanation.

Warning: Math ahead! Proceed at your own risk.

The amount of energy being used can be calculated if you know a few things:

-

- How much protein is synthesized by muscle in a given hour (this is called fractional synthetic rate, or FSR).

- How much muscle somebody has.

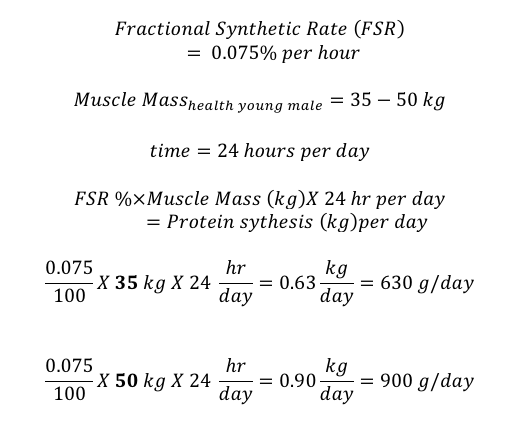

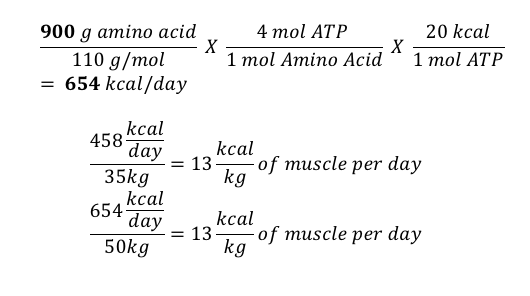

The average fractional synthetic rate (FSR) of muscle protein is about 0.075%/hour [3,4].

Now, the average young, healthy man is about 35 to 50 kg (77 lb to 110 lb) of muscle. (Note, we are referring only to muscle, not lean body mass.) [3,4].

Voila! An average healthy male with 35-50 kg of muscle makes about 630 g to 900g of protein per day.

(For comparison, a frail elderly woman has about 13 kg of muscle. We will leave the calculations to you, but obviously, she will be making less protein.)

To determine what this means in terms of energy use, we need to do a little more math.

Four moles of ATP (energy cells use) are required for each mole of amino acids used to make protein. One mole of ATP releases 20 kcal of energy.

So, using the average molecular weight for amino acids of about 110 g/mole, we can calculate the amount of kcal used per day to make protein [3, 5,6].

Energy used per day by 50 kg of muscle:

Clear as mud?

Well, to repeat, it boils down to an extra 13 kcal/kg of muscle.

Robert Wolfe, one of the biggest researchers in the muscle synthesis field, rounds this number down to about 10 kcal/kg per day [3].

How much does this matter?

Either way, you might be thinking: Big deal. Muscle doesn’t seem to give a significant metabolic advantage. Right?

Well, not exactly.

First, the 10 kg to 13 kg figure is likely an underestimation [3].

Second, remember that a frail elderly woman has a muscle mass of 13 kg compared to 50 kg for a healthy, young male.

That works out to 37 kg of muscle difference.

Which means that Granny is using lots less energy than our hypothetical young man.

Instead, she is likely to be gaining fat. Possibly lots of it. And she wonders why it is accumulating so much faster than when she was younger (and more active…and…um…slightly more muscular).

Meanwhile, if she had more muscle mass, she would be using more energy just by sitting in her rocker!

Okay, realistically, Granny isn’t going to put on 37 kg (81.5 lb) of pure muscle this year – or ever.

But she could put on some muscle, or at the very least she could slow down how much muscle she loses each year. And by doing that, she will decrease the fat she gains.

In terms of what’s possible, if a little optimistic – a five kg (11lb) weight gain in muscle works out to 50 kcal per day, or 2.4 kg (5.3 lb) of fat lost per year – and over 12 kg (25 lb) in 5 years.

Just from resting muscle. This doesn’t include extra calories used for exercise or walking to your car or rocking in that chair or whatever else you do.

The moral of the story? Throw away your scale (or at least hide it for awhile.)

Generally, you don’t need to convince men to gain muscle, but women tend to be more concerned about getting “too big.”

Here’s why women should gain muscle.

Lose weight the easier way

Here’s a familiar scenario. In January, Jane and Bob agree to lose weight – together. Jane watches what she eats, counts every calorie, and spends hours on the treadmill every day. After a month, she’s down by a pound.

Meanwhile, Bob decides to drink less soda and manages to cut down to one can a week from his usual four. He gets to the gym when he can – maybe three times a week – but half the time, he ends up cutting his workout short. One month of this, and he is ten pounds lighter!

What the heck? Why does this happen? (I can hear women around the world gnashing their teeth from here.)

There are many physiological reasons, but the difference in their muscle mass is one of the biggies.

Let’s compare two women. Jane and Mary both have the same amount of fat, but Mary has an extra 7 kg (15 lb) of muscle.

If, for one year, Jane did exactly what Mary did to maintain her weight–snowboarding, sleeping, swearing in six languages, whatever–Jane would actually gain 3.3 kg (7.3 lb) of fat, increasing her body fat percentage to 35.8%. Just because of the differences in their resting muscle mass.

The other thing you might notice is that since Mary has more muscle and weighs more overall, despite having the same amount of fat, she actually has a lower percentage of body fat.

Weight versus size

Since muscle is more dense than fat, 1 kg of muscle will take less space than 1 kg of fat. Muscle is 1.06 kg per liter of space and fat density is 0.9196 kg per liter of space.

If you gained 10kg of muscle at the same time you lost 10kg of fat, you would be smaller. About 1.4 liters smaller. On the scale you would weigh the same. But your pants would be looser.

Let’s say you and your friend decide to start two different weight loss programs at the same time. After 6 months, you’ve lost 10 kg by working out and eating right, while your friend has lost 11 kg by lying in bed drinking coffee and smoking.

Your 10kg scale weight loss might equal a 10 kg muscle gain with a 20 kg fat loss. If so, you’d be 12.3 liters smaller.

On the scale, it would look like your friend who lost 11 kg (9 kg of muscle and 2 kg of fat) was doing better, but in fact, she’d only be 10.7 liters smaller, making her 1.6 liters (3.8 pints) bigger than you. Ha!

Meanwhile, going forward, who will maintain her new weight more effectively? It sure won’t be your friend.

Of course, this is an oversimplification, because muscle and fat are not the only things at play. But the message is the same – losing weight is very different from losing fat.

Research question

This week I review the paper that JB mentioned in his Facebook post.

Willis LH, Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Shields AT, Piner LW, Bales CW, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults. J Appl Physiol. 2012 Dec;113(12):1831-7.

Methods

When it comes to making sense of studies like the one under review, it is really important to take note of the methods. What exactly was done?

The problem of measuring resistance training

Before I get into the particulars of this study, you need to understand that studies about resistance training are notoriously difficult to do.

Why? Well, they’re more involved than aerobics studies, potentially more dangerous, and it’s nearly impossible to measure subjects’ efforts in resistance training. In fact, the only thing that sucks more than resistance training studies is a bad workout!

It’s easy to get annoyed when you read about what is typically done in resistance studies. Really: Subjects did three sets of 10 reps, three times a week, for months! Same exercise, same order, same rest, with maybe an increase in weight. That’s not how anybody really trains! Can’t they come up with anything better?

Not only that, but most resistance training studies use machines to minimize the need for supervision and teaching the exercise. Remember, most subjects are untrained people who in many cases are overweight and have never exercised. Researchers generally don’t have the money to pre-train people before the study starts, and people don’t want to commit to a longer study.

Even if the researchers did take the time to teach subjects to move properly with free weights, they would then need someone to supervise and spot them. One-on-one spotting could take up to 80 hours a week with only 20 exercisers.

Put it all together and you can see why using machines becomes a more attractive alternative, even though machines are not as effective.

Aerobic exercise, on the other hand, isn’t that hard to teach and doesn’t need a lot of supervision. Jump on a bike, run, or step – you’ve been able to do that since kindergarten.

Lastly, the big unknown with resistance training is how hard the volunteer is trying. What is really the heaviest this person could lift? It’s really tough to measure.

Aerobic training doesn’t present this problem because you can use gas analysis and blood sampling to tell if someone has hit their peak oxygen utilization capacity (VO2peak). Meanwhile, effort can be tracked with some combination of a heart rate monitor and the onboard monitoring equipment. With downloadable software and weekly checks, researchers can see exactly how much exercise subjects do and the intensity – to the tenth of a calorie.

That’s why it’s tough to make a scientific comparison of aerobics and resistance training.

Now, on to what the researchers did in this study.

Study volunteers

On the positive side, this study included a lot of participants (196) and it went on for months — eight months, to be exact.

Something pretty unique about this study is the age range of the volunteers, who ranged from 18 to 70 years old. That’s 52 years between the youngest and the oldest!

While I think it’s a good thing to have a varied group, this may be taking things a little too far, since it is tough to generalize about any particular age group based on these results.

After all, it seems fair to assume that Granny and 20-year-old jock Joey are going to respond very differently to an exercise regime. Too bad there was no meta-analysis to see whether and how that was true.

Exercise training

After the volunteers signed up for the study there was a 4-month control period to get rid of less motivated recruits before the researchers put the volunteers into one of three groups.

Group 1: Resistance training (66 volunteers)

- Exercised 3 days a week

- 8 exercises with machines that targeted major muscle groups*

- 3 sets per exercise

- 8 to 12 repetitions per set

- 180 minutes of exercise per week

- Once a volunteer could lift a weight for 12 reps for all three sets the weight increased by 5 lb.

*Note: they didn’t mention it in this article, but in another article based on the same study there were two different resistance training workouts depending where the volunteers were working out. Mostly they used Cybex machines, but at one location they switched to free weights for upper body exercises. No mention about the exact exercises.

Group 2: Aerobic training (73 volunteers)

- Exercised 3 days per week

- Jogged about 12 miles per week (19.3 km)

- 65-80% of VO2peak (moderate intensity)**

- About 130 minutes of exercise week

- Treadmill, elliptical and stationary bikes were used for the aerobic training.

**65% of VO2peak at the beginning of the study would be moderate intensity but as the volunteers exercised over the 8-month period they would be working at a higher percent VO2peak to keep them challenged.

Group 3: Aerobic and resistance training (57 volunteers)

- Aerobic training (12 mile/week at 65-80% VO2peak)

- Resistance training (8 exercises, 3X8-12, 3 times/ week)

- Over 5 hours per week of exercise.

Results

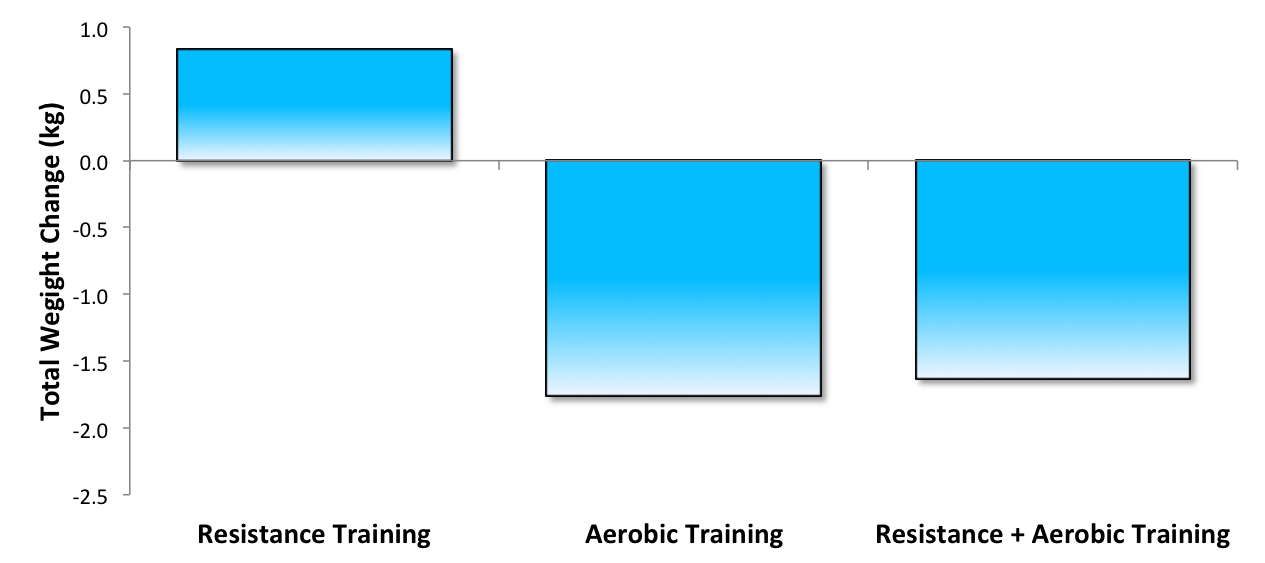

Group 2, the aerobic training group, lost the most weight — an average of 1.76 kg (3.88lb). The combination group (aerobic + resistance) lost an average of 1.63 kg. (See Figure 2).

The resistance training group actually gained 0.83 kg.

Now, if you stopped reading here, you’d come away with the misguided idea that if you want to fit into your skinny jeans or see your toes, aerobic training is the way to go.

Not so fast.

As you probably figured out from the earlier discussion, losing weight is not necessarily a good thing. You can lose weight in a whole lot of ways and most of them aren’t good for you nor do they translate into fat loss.

When people talk of weight loss they usually think of fat loss, but one is not the same as the other.

So. How did these groups compare when you look at the kind of weight they lost?

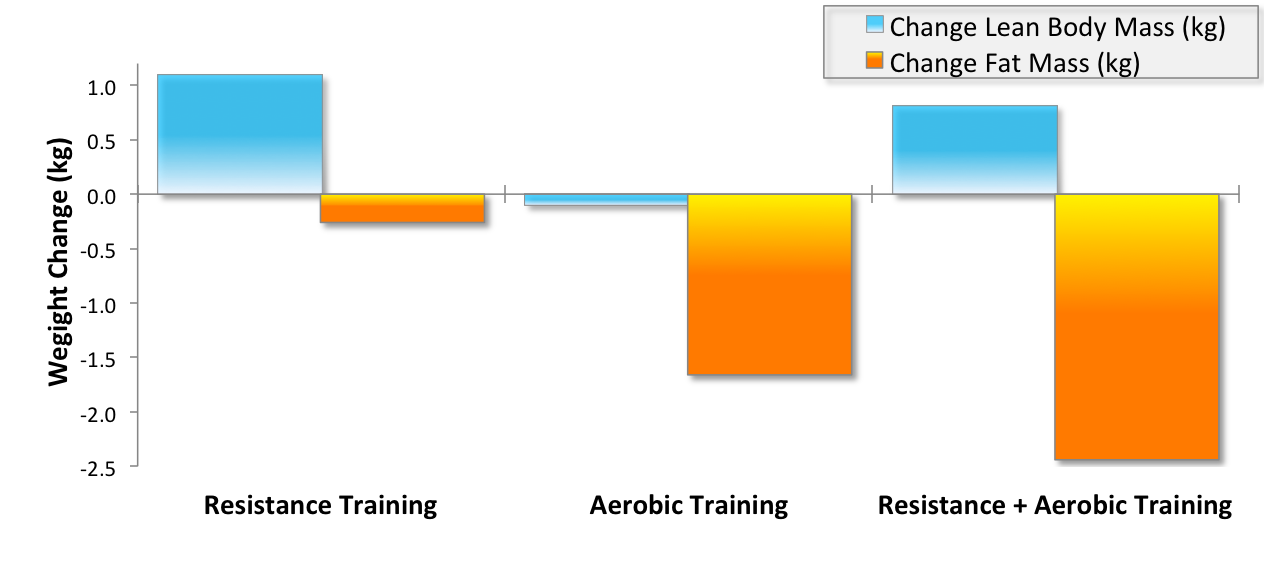

Here’s where things get tricky. And this is why you should be very suspicious of your bathroom scale. The aerobic group lost lean mass (0.10kg). Not good.

Meanwhile, subjects in the combination group and resistance training groups gained lean mass, 0.81 and 1.09, respectively (see Figure 3).

Next time you step on the scale and freak out — “I gained weight! But I was sooooo good last week!” — take a deep breath. If you really were good, maybe you picked up adamantium skeleton along the way. No? Well, maybe you gained a bit of water… or some lean muscle mass. Not a bad thing.

You want to lose fat. Not just weight.

And in this study, the aerobic training group lost 1.66 kg of fat, not quite as much as the combination group, where participants lost 2.44kg of fat. Group 1 (resistance training alone) lost the least amount of fat 0.26 kg (Figure 3).

In other words, combination training led to the greatest improvements in body composition.

The rest of the story: drop outs and exercise time

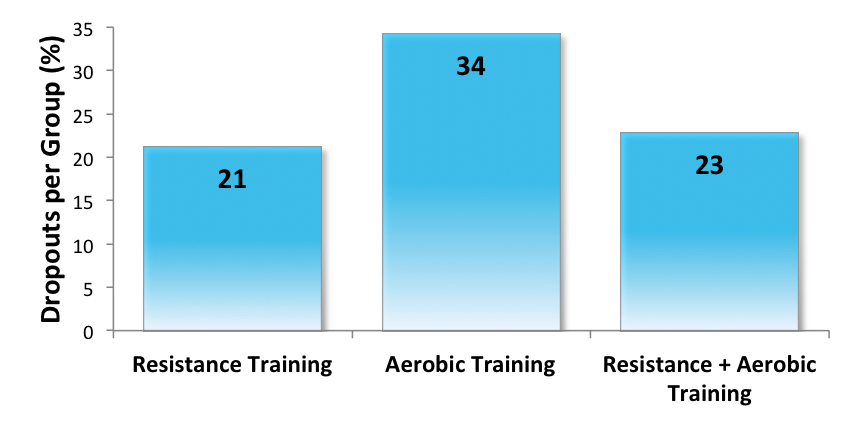

Buried in the study is one of the most important and interesting findings. Resistance training decreased dropout rates (see Figure 4).

Nearly, 35% of volunteers in the aerobic training group dropped out.

Of those, 44% said it was because they had no time.

Okay… maybe so. But look at the combination group, with a dropout rate of only 23%. They were in the gym twice as long as the aerobic exercisers — 314 minutes/week vs. 134 minutes/week.

Both groups who did resistance training showed lower dropout rates. Which is pretty important if the goal is long-term lifestyle change.

Actual time spent exercising

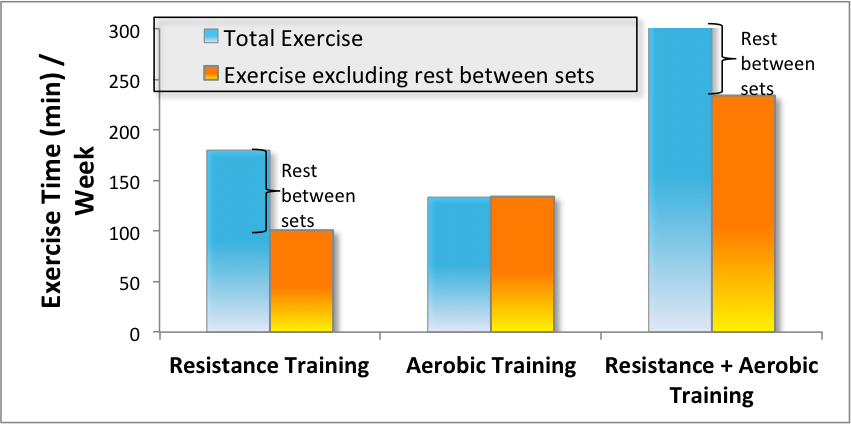

Another relevant but unexplored question is how much exercise each group actually performed.

Through a process of self-experimentation, I estimated that each set of resistance exercises would take no more than 84 seconds, with 24 total sets per workout. Since the researchers included the total exercise times per week, I was also able to estimate the rest between exercises.

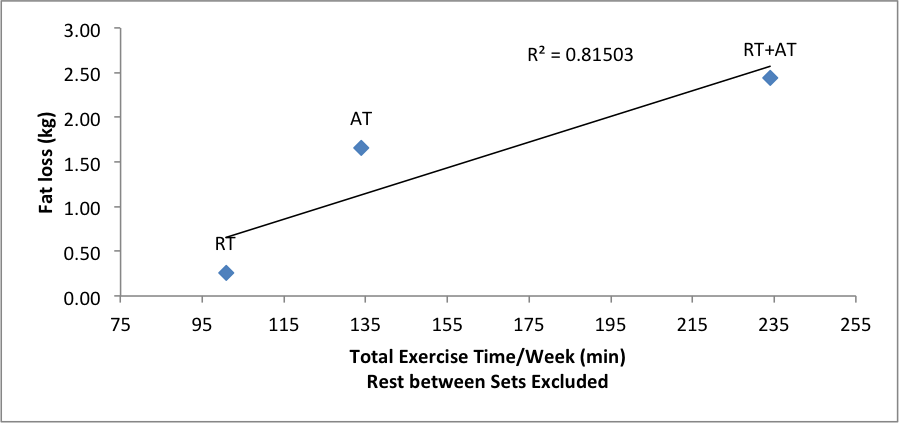

If you take a look at Figures 5 and 6, they show total exercise time (including rests between sets during weight training) and total exercise time minus rest. And lo and behold: Fat loss in this study is more closely related to actual exercise time than it is to exercise type.

VO2peak – Cardiovascular fitness

Resistance exercise alone increased cardiovascular fitness (VO2peak). It doesn’t improve cardio fitness as much as aerobic training or combination training, but does improve it.

Keep in mind that the resistance training in this study was not designed in any way to stress the cardiovascular system. Even so, there was a nearly 5% improvement in cardiovascular fitness (increase of 1.26 mL/kg/min in VO2peak). Not bad, considering that VO2peak is thought to improve somewhere between 5-15% with targeted training. (This varies a bit depending on how fit you are to start.)

Too bad the researchers didn’t measure the strength of the aerobic group to see if they experienced similar crossover training effects.

Conclusion

A quick glance at this study might lead you to Science Daily’s conclusion: “Aerobic Exercise Trumps Resistance Training for Weight and Fat Loss.”

Usually Science Daily is pretty good at summing up the essence of studies, but they really missed the boat this time.

Aerobic exercise did lead to more weight loss – a grand total of 1.76 kg (3.88lb) after 8 months, of which 0.1 kg (0.22 lb) came from muscle.

But:

- The combination aerobic/ resistance training group lost the most fat while gaining muscle.

- They had lower dropout rates compared to the aerobic group, and improved cardiovascular performance.

- This group also spent the most time working out, just over 5 hours a week.

From this study, I’d conclude that a combination of aerobic and resistance training and working out 5 hours a week was the best for fat loss and cardiovascular fitness.

Note also, that while this study compares aerobic training and resistance training as if they are completely distinct entities, that isn’t, in fact, the case. The real fat-loss magic results from resistance training that is also aerobically demanding (metabolic resistance training).

Below is a partial list of references that Dr. Berardi posted on his Facebook page.

Bottom line

Your bathroom scale lies to you. (Or at the very least you are talking two completely different languages).

When you weigh yourself on the bathroom scale it gives you a number that is your weight. Weight is not fat mass. Your scale says weight and you think fat.

When you lose weight you’re very happy, because you think you’ve lost fat! When you gain weight you’re very unhappy, because you think you’ve gained fat!

If you lose or gain weight it could be a lot of things, like water, carbohydrate, last night’s dinner and/or fat. So, when it comes to recognizing fat loss, you need to look at how your clothes fit, at how you feel, and at the scale over weeks – not just one day.

And, of course, if you want to lose weight and fat, a combination of resistance exercise and cardio is likely best.

However, you might not need a full 5 hours a week to get started in the right direction. See this article for a more minimalistic approach to getting in shape.

Eat, move, and live…better.©

The health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it doesn’t have to be.

Let us help you make sense of it all with this free special report.

In it you’ll learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies – unique and personal – for you.

Click here to download the special report, for free.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Share