Worried about Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration? There are many things we can’t control when it comes to cognitive decline. But certain nutrition and lifestyle choices may help to lower our risk. Here’s how to stack the deck in your brain’s favor.

- Want to listen instead of read? Download the audio recording here…

++++

A few years ago I was playing a game with my family. The question came up:

“Which illness do you never want to have?”

(Apparently my family plays dreary games.)

Each person around the table said:

“Alzheimer’s disease”.

Then the conversation turned to how inevitable this illness seemed, and the mood became quite bleak.

This made me stop and think.

Most of us believe, to some degree, we can take steps to prevent heart disease, diabetes and stroke.

Yet, unlike these, many of us feel like getting Alzheimer’s is pure genetic luck (or doom, depending on your circumstances).

Is this accurate?

Can we do anything in our daily life that might help prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline?

In this article, we’ll explore this question. In particular, we’ll address:

- What Alzheimer’s disease is.

- What factors contribute to Alzheimer’s and neurodegeneration.

- What factors may help us prevent Alzheimer’s, and what you can do to protect your own brain (or help clients / loved ones avoid the disease too.)

We’ve even included an Alzheimer’s Prevention Quiz to find out how well you’re stacking the deck in your brain’s favor!

In the end, it’s great that you’re reading this because, let’s face it…

We all have good reason to be worried about Alzheimer’s disease.

To be fair, my family wasn’t being unusually morbid or paranoid.

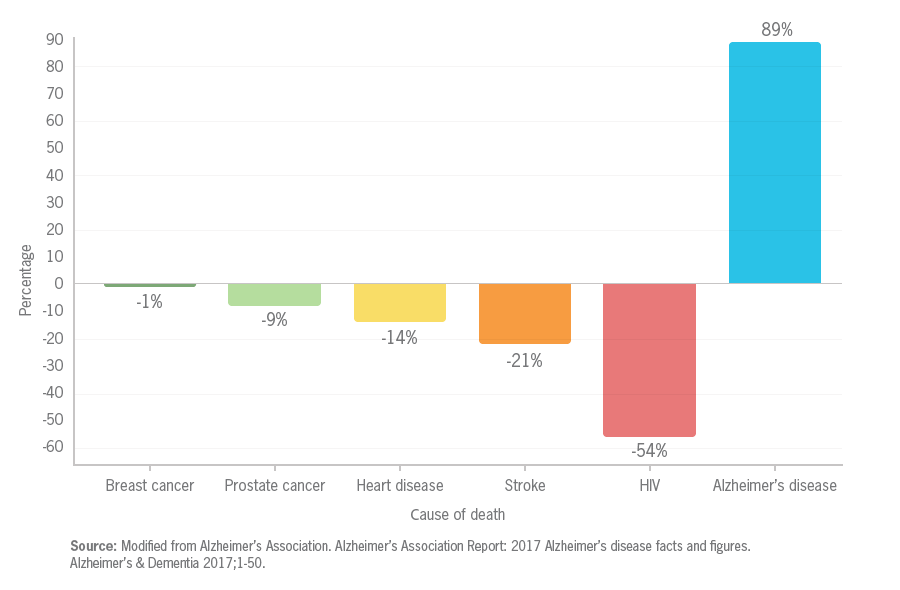

Deaths from Alzheimer’s increased 89 percent between 2000 and 2014. That might not sound too remarkable… until you compare it to the 21 percent and 14 percent decrease in stroke and heart disease deaths during the same time period (see image below).

This now makes Alzheimer’s the sixth leading cause of death in the U.S., with cost of care now equal to or exceeding cardiovascular disease or cancer.

What is Alzheimer’s disease?

If you’ve had someone in your family affected by Alzheimer’s, maybe it appeared subtly.

- At first, maybe your mom was a little less steady on her feet, or sometimes forgot words for things.

- Maybe your grandfather got more irritable, or seemed more rigid about household rules.

- Maybe your aunt joked about being absent-minded, perhaps to cover up some puzzling behaviors.

Later, maybe it got worse.

- Maybe a close relative no longer recognized you. Or knew what day, or what year, it was.

- Maybe someone’s personality changed completely; perhaps they went from a gentle teddy bear to a raging grizzly.

- Maybe someone got lost and scared in their own driveway, or their own neighborhood, or went wandering to a place where something used to be 30 years ago.

- Maybe someone with a second language forgot it, and regressed to speaking only the language they first learned as a child.

Sometimes this process of neurodegeneration is fast. Sometimes it’s slow, perhaps up to 20 years between the first symptoms and significant impairment.

This process can also range from mild to severe.

- Mild: People might have trouble with short-term memory (e.g., names of people they just met, forgetting something they just read, not being able to remember where they put a set of keys, etc.). Otherwise, they can take care of themselves and function pretty well.

- Moderate: People might need help with daily tasks, since now they’re having real trouble with long-term memory, daily self care, and concentrating. They might forget important details about their personal histories, like where they live. They might not always know what day it is, or where they live. They might also have problems with other brain processes like sleep. They might feel more fearful, or angry, or have other major emotional and personality changes.

- Advanced: At this phase, people need full-time care. Though they may have occasional moments of clarity, they generally aren’t very aware of their surroundings, able to communicate clearly, or do most physical tasks.

Given all the possible manifestations of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, it’s understandably scary.

At the most basic level, Alzheimer’s damages neurons in the brain.

Brain cells more or less make us who we are, and enable us to do all the activities of life. You can imagine that damage to these cells can affect a wide range of processes, including:

- remembering, recognizing, recalling (both short-term and long-term)

- speaking and writing

- making decisions and solving problems

- interpreting sensory input

- finding our way around and navigating the world

With enough damage to neurons, we may die.

We aren’t yet completely sure why and how the neurons get damaged.

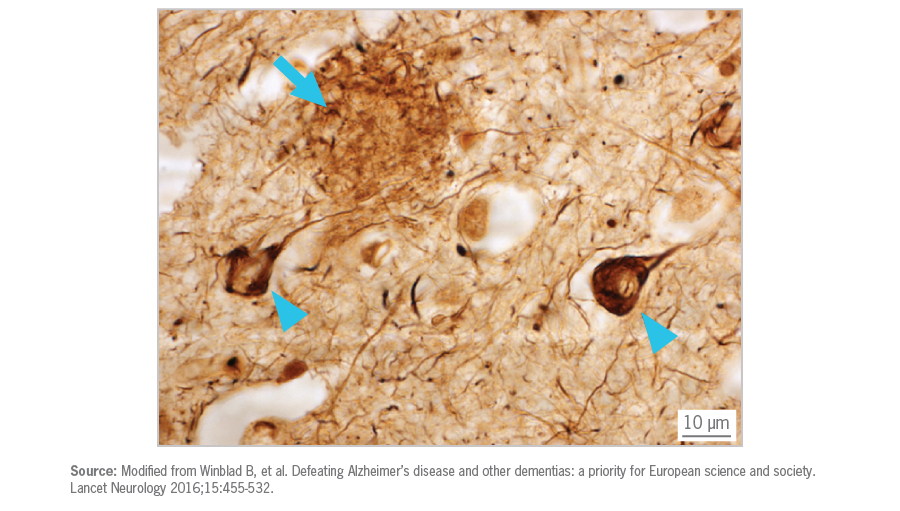

The most common working hypothesis right now is that, essentially, protein-based “gunk” builds up in and around brain cells, sort of like clothing fibers and cat hair clogging up your dryer lint filter.

More specifically:

- Beta-amyloid plaques build up outside of neurons.

- Tangles of other protein fibers can build up inside of neurons.

This accumulation of neurological protein “gunk” can interfere with neuron-to-neuron communication as well as nutrient transport (and the transport of other essential compounds, like neurotransmitters).

The neurons that first become damaged are often in regions of the brain that shape new, short-term memories. Then the damage proceeds to areas that control long term memory.

But are beta-amyloid plaques to blame? Or are they just byproducts of another process?

Clinical trials using medications to suppress beta-amyloid synthesis haven’t been encouraging so far. Thus, some researchers speculate that our bodies may synthesize beta-amyloid plaques as a protective mechanism when lipid supply is low and neuron metabolism is overly dependent upon glucose.

In other words, beta-amyloid plaques may be an effect, rather than a direct cause, of Alzheimer’s. As with most chronic diseases, it’s probably a complex collection of factors.

Other contributing elements may include:

- Misfiring neurons. (When the neurons might be structurally OK, but the chemical information flow from neuron to neuron isn’t working.)

- Uncontrolled inflammation. (This is when inflammation goes wild, and instead of being helpful, it just damages structures in the brain.)

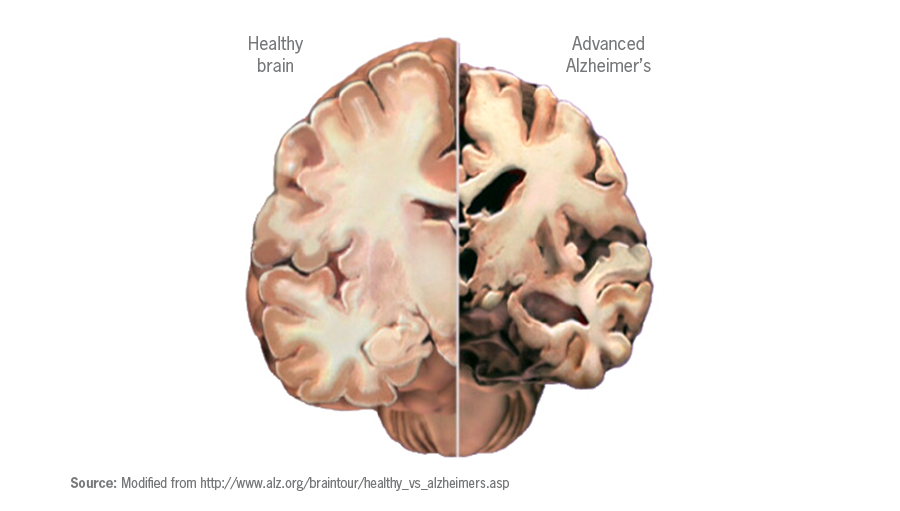

- Thinning of gray matter. (When brain tissue that’s particularly full of nerve cells decreases.)

- Generalized brain atrophy. (Most people know that it’s possible to lose muscle mass, which can lead to decreases in strength and function. This can also happen to our brain mass).

Many risk factors for Alzheimer’s are outside of our control.

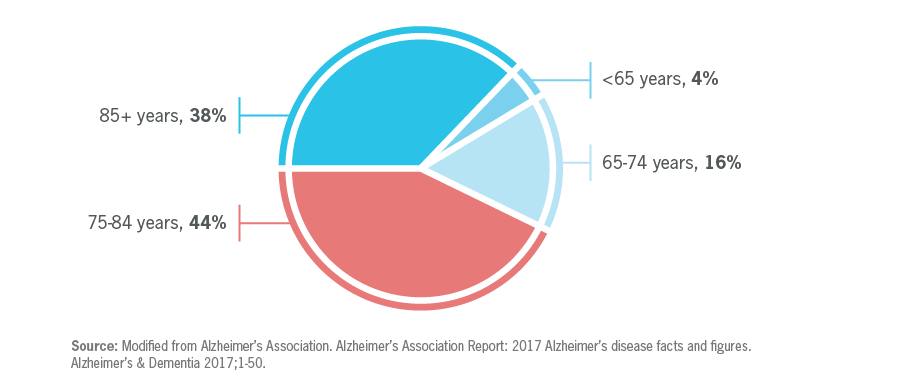

Getting older is our main risk factor.

And with people generally living longer, prevalence of Alzheimer’s is expected to quadruple by 2050, meaning 1 in every 85 people will be affected.

Around 5.5 million people are known to be living with Alzheimer’s in the U.S. Most are over 65. But there may be more, since Alzheimer’s is often under-diagnosed and/or under-reported.

Getting diagnosed with Alzheimer’s before age 65 is rare, and it seems to happen only to a very small percentage of people (2-5 percent of all cases) with particular genetic mutations.

While Alzheimer’s is more common with advanced age, it’s not guaranteed, and it’s not a “normal” part of aging.

Women get Alzheimer’s more often than men.

For instance, in the U.S., two-thirds of people with Alzheimer’s are women.

This might simply be due to women living longer.

Also consider that if a man makes it to age 65, this means he hasn’t died of a cardiovascular condition, which means he probably has above average cardiovascular health, which would decrease his chances of Alzheimer’s (more about the interaction between Alzheimer’s and vascular health later).

Sex hormones, such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, have complex effects on the brain.

Endogenous sex hormones (in other words, the hormones we naturally produce) may protect against cognitive decline. For instance, the estrogens that most women’s ovaries secrete before menopause can help brain cells and structures grow, stay healthy, and transmit signals; they can also help prevent cell death.

Yet some evidence suggests that supplemental hormones, such as postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy in women (usually conjugated estrogens with progestins) may increase dementia risk along with other cardiovascular disease risks.

Data here is still unclear, and outcomes may depend on other factors like age or the exact type of hormones supplemented.

In men, age-related hormonal changes as well as treatments such as androgen blocking therapy (for instance, to treat prostate cancer) can also affect cognitive function.

Genetics plays a role.

Genetics and epigenetics are complex, but researchers have identified some key genetic variations that may contribute to one’s risk of Alzheimer’s, at least in certain populations.

We know that Alzheimer’s tends to run in families, which hints at a genetic link. Genetic variations of this type often cluster within a closely related population, which means that someone’s ethnicity and ancestry may also be a factor (more on this below).

One of the known genetic risk factors in developing Alzheimer’s disease is a variant on the APOE gene, which codes for the protein apolipoprotein E, a cholesterol carrier found in the brain and elsewhere in the body.

Apolipoproteins help shuttle cholesterol and lipids from the liver to the rest of the body. Cholesterol and lipids are abundant in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

People with Alzheimer’s might lack certain lipids and/or cholesterol in their CSF. Having enough of these compounds around in the brain is important for general brain health, neurotransmission, and could offer protection against other problematic substances. Thus, variations in apolipoproteins might affect the “delivery mechanisms”.

The APOE protein comes in three forms: E2, E3, and E4. The APOE-ε4 gene variant (the “ε” is the Greek letter epsilon) is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s in many populations, and this risk seems to include people of European, African, and East Asian descent.

- Having one copy of APOE-ε4 leads to a three times greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

- Having two copies means an 8 to 12 times greater risk.

Keep in mind that carrying APOE-ε4 doesn’t mean someone is guaranteed to get Alzheimer’s.

- Some people with APOE-ε4 don’t get Alzheimer’s.

- Some people without APOE-ε4 do get Alzheimer’s.

Genetics is about probabilities, not absolutes. Many biological phenomena work together in ways we can’t predict.

Researchers speculate that having these and other genetic risk factors may affect about one-third of the formula for how our brains change with age.

For instance:

- Having a female relative (such as a mother) with Alzheimer’s seems to increase risk more than a male relative.

- Having other genetic risk factors (such as having Down syndrome) may also predispose people to neurodegeneration. In fact, 30 percent of those with Down syndrome in their 50s have dementia. This might be due to a genetic difference that leads to a greater buildup of plaques and tangles in the brain at an earlier age.

The other two-thirds of non-genetic factors might, to some degree, be up to us and our environments. (More on this below.)

An important caution: Right now, we can test for the APOE4 gene, as well as other genetic factors. But we can’t say for sure whether having this gene truly predicts whether you will get Alzheimer’s. So, be careful with these and any other genetic data that you get about yourself.

Ethnicity is another risk factor.

Our ethnicity and ancestry reflect potential clusters of genetic tendencies as well as other socioeconomic factors.

For instance:

- In the United States, people of African American and/or Hispanic descent seem to get Alzheimer’s more than people of white European descent.

- In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are diagnosed at rates three to five times higher than the non-Aboriginal population.

- In studies done in Singapore in a multi-ethnic population, people with Chinese ancestry had lower rates of dementia than ethnic Malays or Indians. South Korea has over twice the rate of dementia diagnoses compared to the rest of East Asia.

- 20 percent of people over 65 in Israel will eventually be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, potentially reflecting risk factors within various ethnically Jewish populations.

- Scandinavian countries have the highest death rates from Alzheimer’s (ranging from around 30 percent for Denmark to 54 percent for Finland), perhaps because people there generally live longer (and so are more likely to end up with age-linked diseases)… or perhaps because of some other genetic factors in Northern Europeans (ethnic Finns, for instance, have higher rates of cardiovascular disease as well).

Given these diverse populations, our risk for Alzheimer’s probably isn’t just about genetic ancestry.

Health is, in part, also socially determined.

As with other chronic diseases, there are probably other social and economic factors that contribute to health, such as social inequality, poverty, language barriers, lack of public health resources for specific populations, being able to afford medical care, and so forth.

For instance:

- Across Europe, there are significant differences in how quickly people receive care after first noticing symptoms: In Germany, you might get treatment within a year; in the UK you might wait three years.

- In Latin America, Colombia has a dementia diagnosis rate of about 2-4 percent; its neighbor Venezuela has a rate of 8-13 percent; and another neighbor, Brazil, has around 5 percent; its southern cousin Argentina has 12 percent.

- People of African ancestry living in the United States get Alzheimer’s at much higher rates than populations of Africans living in Africa.

- Speaking of nationality, there’s evidence that people who speak more than one language get Alzheimer’s less, regardless of ethnicity.

So: It’s complex, like all chronic diseases.

Head trauma: Also not good.

It should be intuitively obvious that taking damage to your head isn’t great for your brain.

Some types of head trauma, like sports-related concussions, are (or should be) relatively preventable.

Other types, such as accidents or combat injuries, are less so. Many veterans, for instance, are grappling with the long-term effects of traumatic brain injury, or TBI.

Many risk factors we can do something about.

OK, so, we can’t ditch our genetics, our parents, or time. We may not be able to move to some imaginary affluent egalitarian society with a perfect health care system.

As expected, brain health (and deterioration) is influenced by many factors outside of our control, including trauma we’ve experienced, air we’ve breathed, crayons we may have eaten, and so forth.

Nevertheless, there are some factors we can control. (Some, you can control a lot, some only a little. But all can be changed, even if only slightly.)

Instead of just giving you a long list of these factors, we’ve created an Alzheimer’s Prevention Quiz (below).

Use this quiz to take stock of the things you can influence in your own life, to help reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s and neurodegeneration.

Note: This quiz isn’t about ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, it’s about understanding the things you’re already doing — and the things you could do, or do more of — to support your brain health and stack the deck in favor of avoiding Alzheimer’s.

Your Alzheimer’s Prevention Test: How do you score?

As you read through the following sections, give yourself a score for each. Once you’re done, look at your answers, and ask yourself:

Could I change or improve these factors, even just a little bit?

We’ll look at what you can do below.

Part 1: Metabolic factors

At rest, the brain uses 20 percent of the body’s oxygen and energy. If your heart and vessels aren’t working properly to deliver blood and nutrients, or if our metabolism is disrupted, our brains suffer too.

Is your blood sugar under control?

Some researchers have suggested that Alzheimer’s could be called “Type 3 diabetes”.

This is because chronically elevated blood sugars (and blood insulin) seem to increase inflammation, as well as influence the size/development of the hippocampus (a brain structure essential to learning and memory).

If someone is diagnosed with diabetes, their risk of Alzheimer’s doubles; estimates also suggest that 81 percent of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s have impaired glucose metabolism.

Has your doctor ever told you that you have poor glucose control, or have you ever been tested for this? Have you ever been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes?

- I’m healthy, everything’s good – 3 points

- Some mild blood sugar issues – 2 points

- I know I have significant issues and/or Type 2 diabetes – 1 point

- I’m not sure, but now I wonder – No problem, go get it checked out

Are your blood lipids and cholesterol in a healthy range?

Our brains and their cells are fat-based, so changes to lipid (fat) metabolism will affect brain health as well as oxidation and inflammation. Having a poor lipid profile isn’t just about heart disease (as we tend to assume) — it’s about brain health too.

Have you had your blood lipids (HDL, LDL, triglycerides etc.) and cholesterol checked? Are they in a healthy range?

- I’m healthy, everything’s good – 3 points

- Some mild blood lipid issues – 2 points

- I know I have significant issues (e.g. high triglycerides) – 1 point

- I’m not sure, but now I wonder – No problem, go get it checked out

Is your blood pressure in a healthy range?

Vascular health is brain health. Higher blood pressure can damage the small blood vessels of the brain, and people with high blood pressure in their younger years tend to develop neurodegeneration later.

Have you had your blood pressure tested recently? Is it in a healthy range?

- Yep, rockin’ that 120/80 or less – 3 points

- Some mild concerns; I’m between 120/80 and 140/90 – 2 points

- I know I have high blood pressure, over 140/90 – 1 point

- I’m not sure, but now I wonder – No problem, go get it checked out

Is your body fat in a healthy range for you?

Adipose tissue, aka body fat, is metabolically active tissue that secretes hormones and other cell signalling molecules.

Because of this, when we have too much body fat, particularly visceral fat around our internal organs, we risk having higher inflammation and metabolic disruption.

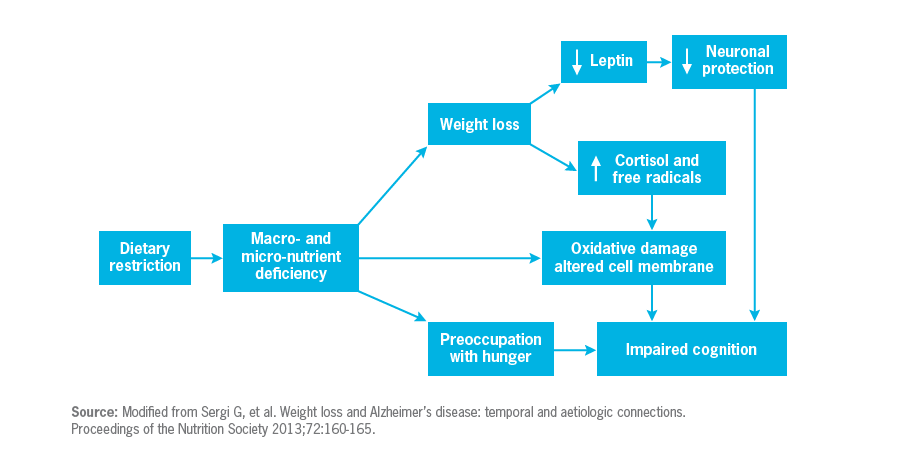

But past a certain point, lower isn’t better. If our body fat / weight is too low for us, it might mean we aren’t eating enough, aren’t keeping that valuable lean mass, and/or risk nutrient deficiencies. (Or we have some other health problem that is causing us to lose weight.)

There may also be some link with leptin (a nutrient-sensing, “anti-starvation” hormone) and brain health. When weight / fat mass drops, so does leptin. As with body fat, we want leptin levels to be healthy and normal — neither too much nor too little.

Is your body fat level in a healthy range for your age, body type, and sex?

- Yes – 3 points

- I’m carrying a little more body fat than I think I should – 2 points

- I’m carrying significantly more body fat than I probably should – 1 point

- I’m carrying significantly less body fat than I probably should – 1 point

- I’m not sure, but now I wonder – No problem, go get it checked out

Part 2: Dietary factors

What’s your overall diet pattern?

Do you eat something along the lines of the diets that we know are associated with lower risks of chronic disease? For instance, a traditional Mediterranean, Japanese, and/or Scandinavian type diet?

These types of diets are typically rich in antioxidants, B vitamins, and anti-inflammatory fats. Plus, they tend to include foods containing phytonutrients that may help with brain health; for instance, by:

- improving synaptic plasticity (i.e. “wiring and rewiring” our brain pathways to help us learn),

- improving cell signaling pathways,

- improving blood flow to the brain, and/or

- reducing harm from beta-amyloid plaque buildup.

Phytonutrients (i.e. plant nutrients) may partly explain why people eating a diet with lots of plants have a significantly lower risk of developing dementia than folks who don’t.

Many world cuisines and traditional diets also include herbs and spices that have protective properties. For instance:

- Curcumin appears to be many things ‘anti-’ -amyloidogenic, -oxidative, and -inflammatory.

- Saffron, cinnamon, and ginger have shown to be powerful anti-inflammatories.

- Garlic appears to be neuroprotective through several mechanisms.

If some of these anti-inflammatory outcomes could be translated to brain health, they might play a role in the prevention of Alzheimer’s.

Give yourself one point for any of the foods below that you regularly eat.

(Don’t get too bothered if you don’t eat some of these because of preference or food intolerances, or if your favorite “healthy food” isn’t on the list. The idea is just to bring awareness to some of the nutrient-rich choices you are including.)

- Colorful fruits (e.g. dark coloured berries, citrus, etc.) – 1 point

- Dark green leafy vegetables (e.g. spinach, Swiss chard, etc.) – 1 point

- Other green vegetables (e.g. broccoli, green beans) – 1 point

- Other colorful vegetables (e.g. red peppers, purple eggplant, orange carrots, etc.) – 1 point

- Garlic and/or onions – 1 point

- Beans and/or legumes (e.g. lentils, chickpeas, etc.) – 1 point

- Nuts and/or seeds (e.g. walnuts, pumpkin seeds, etc.) – 1 point

- Fish, especially oily fish (e.g. salmon, herring, etc.) – 1 point\

- Seafood (e.g. shrimp, squid, etc.) – 1 point

- Wild game (e.g. venison, elk, etc.) – 1 point

- Whole grains (e.g. brown or wild rice, buckwheat, etc.) – 1 point

- Fermented foods (e.g. kimchi, yogurt, sauerkraut, natto, etc.) – 1 point

- Olives and/or olive oil – 1 point

- Herbs and/or spices (e.g. turmeric, cinnamon, etc.) – 1 point

How’s your omega-3 fatty acid intake?

Omega-3 fats are part of neuronal membranes, direct inflammation and immunity, and might influence the formation/clearance of beta-amyloid plaques.

In theory, having enough omega-3 fatty acids available may play a role in brain health. We don’t yet know enough about whether supplementation helps prevent Alzheimer’s, but consistently consuming omega-3 fats (such as through oily fish or other food sources) does seem to be a good idea.

For those over age 60, taking omega-3 supplements in an effort to reverse/prevent Alzheimer’s doesn’t appear to be very useful, likely because it’s too late in the progression.

You might be wondering about the different types of omega-3 fats, specifically ALA (usually from plant sources) compared to EPA/DHA (usually from marine animal sources like fish or krill, though you can also get it from algae).

While our bodies can convert ALA to DHA, we don’t convert it very well, and some people have a genetic variation that converts it even less. This genetic variation has been reported in some people with Alzheimer’s, which begs the question: Might they benefit from direct DHA/EPA consumption? It’s unclear at this point.

How often do you eat foods with DHA / EPA omega-3s in them, such as oily fish / seafood, or supplement with DHA / EPA (whether from fish, seafood, or algae sources)?

- Daily – 4 points

- A few times a week – 3 points

- Weekly – 2 points

- Less than weekly – 1 point

How’s your other fat intake?

Monounsaturated fat (from foods like olives, almonds, and peanuts) appears to be beneficial for brain health too.

Saturated fats are a mixed bag, with data somewhat unclear. It seems that diets lower in saturated fats may reduce Alzheimer’s risk, perhaps because high-saturated-fat diets may make it harder for us to clear beta-amyloid from the brain, along with diminishing overall blood circulation.

While the fatty acid composition of our diets definitely affects the health of our cells, bear in mind that it may not be individual fat types that are to blame.

The negative effects of high-saturated-fat diets often come with other things, like lower omega-3 fatty acids, or higher sugar intake. After all, few people are eating fresh fish and butter as their only fat sources.

The average person typically consumes saturated fats in processed foods that are high in other stuff like salt, sugar, trans fats, preservatives, and so forth.

The fact that saturated fats are typically delivered to us in processed foods may actually be what increases brain inflammation and oxidation more than fat type alone.

Also, when oils (which are rich in fats) are heated to very high temperatures (like for deep frying), they can form compounds called aldehydes that might damage cells in the body. Some speculate that this might lead to neurodegenerative diseases.

How much healthy fat from relatively unprocessed “real foods” do you eat regularly?

Give yourself one point for each.

(Don’t get too bothered if you don’t eat some of these because of preference or food intolerances, or if your favorite “healthy food” isn’t on the list. The idea is just to review some of the nutrient-rich choices you are including.)

- Avocado – 1 point

- Coconut / coconut oil – 1 point

- Olives / olive oil – 1 point

- Nuts / seeds – 1 point

- Peanuts* – 1 point

- Oily fish (e.g. salmon, mackerel, herring) – 1 point

*Wait, why aren’t peanuts a nut? Peanuts are actually a legume, closer to beans and lentils than to “real” nuts like almonds or walnuts.

How varied is your fat intake?

- Very much so – I try to mix it up and eat all kinds of healthy-fat-containing foods – 3 points

- Sort of; I have a few fat sources I like – 2 points

- Not at all; it’s pretty much only one kind – 1 point

- Aerosol spray cheese diet, baby! – 0 points

How often do you eat less-healthy processed fats, like trans fats or processed cooking oils (such as corn oil, hydrogenated margarine, or cooking sprays)?

- Never – 3 points

- Occasionally – 2 points

- Regularly – 1 points

How’s your fruit and vegetable intake?

Fruits and vegetables, especially colorful ones, are good for us and our brains.

They have vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients and antioxidants — and supplementing those compounds doesn’t seem to bring us the health benefits that actually eating our fruit and veg does.

How many servings of colorful fruits and/or vegetables do you eat every day?

- 5 or more – 3 points

- 3 to 5 – 2 points

- 1 to 2 – 1 points

- I hate plants – 0 points

What cooking methods do you use?

Cooking methods can affect the nutrient quality of our foods, and/or potentially increase the amount of harmful chemical compounds in them.

For instance, some cooking and processing methods can increase the amount of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in foods; some researchers suggest that there may be a link between AGEs and Alzheimer’s.

AGEs are most often found in highly processed foods, meats, full fat cheeses, and foods cooked by grilling, frying, and roasting. They have a long half life in the body, and seem to promote oxidative stress and inflammation, along with beta-amyloid plaque development. They can even bind to a receptor in the body that triggers inflammatory disorders and influence apolipoproteins (including APOE4).

(Translation: these AGE guys hang around in the body a long time, and they can do a fair bit of damage while they’re there.)

This doesn’t mean you should quit grilling forever, just that you may consider moderating your intake of grilled foods.

How often do you eat deep fried and/or grilled foods?

- Never – 3 point

- Occasionally – 2 points

- Regularly – 1 points

- I like fried carbon lumps for breakfast, lunch, and dinner – 0 points

Are you getting enough B vitamins?

Getting enough B vitamins (particularly B6, folic acid, and B12) seems to help preserve cognitive function. Conversely, many B vitamin deficiencies can manifest as mental / cognitive health problems.

We get these vitamins from a wide variety of foods: whole grains, beans and legumes, fruits and vegetables, meats / fish / poultry, fortified dairy, and so forth.

If you’re eating a varied diet that includes a broad range of animal and plant foods, and not actively depleting your B vitamins (for instance, with chronic alcohol intake), you’re probably fine.

If you’re an exclusively plant-based eater, consider supplementation, particularly of B12.

How varied is your diet?

- I always eat a wide variety of animal and plant foods (and/or supplement B12); novelty is my bag, baby! – 3 points

- I try out different foods sometimes – 2 points

- I try to eat whole, unprocessed foods but tend to stick to my “routine” – 1 points

- I eat the same thing every day, usually out of a box – 0 points

How’s your gut health?

Emerging evidence is supporting the idea of a link between our brains and our gut health — a connection known as the “gut-brain axis”.

For instance, researchers estimate that about one-quarter of people with celiac disease also have neurological or mental health issues (such as anxiety or depression).

When there is damage to the intestinal epithelium (lining), foreign substances and pathogens can enter systemic circulation, causing the body’s immune system to go on the attack. Even if the foreign substance is relatively benign (such as a partially digested food particle), the body may treat it as potentially toxic and mount a response that may inflame and/or destroy healthy tissues, including brain tissue.

Our microbiome (i.e. the complex inner ecosystem of our friendly bacteria as well as potentially helpful viruses and fungi) can also affect our brain health. For instance, pathogenic bacteria can secrete compounds (such as amyloids and endotoxins) which seem to play a role in the formation of plaques and tangles in the brain, and contribute to excessive inflammation.

This means if our GI microbiome goes out of whack (for instance, with overuse of antibiotics, or something else that harms the delicate balance of the system), we might see neurological problems as the result.

How are you taking care of your gut health?

Give yourself one point for every gut-health-promoting behavior you do:

- I eat fermented foods (e.g. kimchi, yogurt, sauerkraut, or natto) regularly – 1 point

- I am careful not to overuse antibiotics, or antibacterial products – 1 point

- I supplement with probiotics – 1 point

- I am often outdoors, exposed to various types of potentially beneficial microbes (for instance, gardening or working on a farm) – 1 point

- I know about any food intolerances or sensitivities I have, and I am careful to avoid foods that seem to inflame my gut – 1 point

- I eat at least 20 grams of fiber a day from foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans / legumes – 1 point

- I minimize my intake of sugary foods that might promote an unhealthy GI environment – 1 point

- I drink plenty of water to help fiber do its job – 1 point

- I make sure my poo looks good – 1 point

Part 3: Other daily behaviors

How active are you?

If you remember that our brain is in our body, it makes sense that anything that increases blood flow to the body increases blood flow to the brain. More blood to the brain is good.

Regular exercise can also:

- reverse the cell deterioration of aging,

- decrease loss of synapses in the brain,

- increase protective neurotrophic (neuron growth) factors,

- improve insulin signaling pathways,

- decrease inflammatory markers, and

- increase levels of something called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is important in learning and memory.

All good things if you’re interested in preventing Alzheimer’s.

More frequent activity (even if it’s relatively brief, say 15 minutes) seems to be better than less-frequent activity. So consider how you can get more daily-life movement rather than trying to crush yourself at the gym 3 days a week.

I do some kind of purposeful physical movement that gets my heart rate up at least a little bit…

- Every day, throughout the day – 5 points

- Once a day – 4 points

- Every other day – 3 points

- A few times a week – 2 points

- Once a week – 1 point

- Less than once a week – 0 points

How well and how much do you sleep?

Sleep is a master metabolic regulator, and crucial for brain health and cognition (including learning, decision-making, and memory, three key areas affected by Alzheimer’s).

APOE4 has been linked to sleep. And sleep has been linked to how well we can clear beta-amyloid.

How much do you sleep, most nights?

- Fewer than 5 hours – 0 points

- 5-7 hours – 1 point

- 7-9 hours – 2 points

- More than 9 hours, and I’m healthy – 3 points

- More than 9 hours, but I have another health issue (such as depression or chronic fatigue) that is part of this – 2 points

How well do you sleep, most nights?

- Awful. I wake up constantly, can’t get to sleep, have chronic insomnia or issues with sleep apnea, etc. – 1 point

- So-so. Some nights OK, some nights not so great. – 2 points

- Pretty well. I can usually get to sleep and stay asleep – 3 points

- My family calls me “Log” or “Dead Guy”; I could sleep through nuclear war – 4 points

Do you get enough vitamin D?

Vitamin D might help with neural plasticity, calcium balance, and glutathione metabolism, among other things, all helping to preserve brain function.

Sunlight is the best source, with dietary sources being eggs, seafood, liver, and certain mushrooms.

Are you getting enough vitamin D?

- Yes, I try to get outside for a little sunshine every day – 3 points

- Yes, I try to get outside a few days a week – 2 points

- It’s dark and cold where I am right now, but I supplement with vitamin D – 2 points

- It’s dark and cold where I am right now; I have lost my will to do anything but watch Netflix and weep quietly – 1 point

- I have no idea – No problem, consider getting your vitamin D levels tested

Do you smoke?

- No, and I never have – 3 points

- No, but I used to – 2 points

- Yes, occasionally; or I’m exposed to secondhand smoke at work – 1 point

- Yes, a fair bit – 0 points

How often do you drink alcohol, and how much?

Light to moderate alcohol consumption (especially red wine) may have some brain health benefits for some people, but those benefits disappear past a certain point.

How often do you habitually drink alcohol?

- Less than once a month, or never – 4 points

- Somewhere between once a month and once a week – 3 points

- A few times a week or so – 2 points

- Daily – 1 point

- More than once daily – 0 points

If / when you drink, you would normally…

- Have one drink or less – 3 points

- Have 1-3 drinks – 2 points

- Have 3-5 drinks – 1 point

- Have 5 or more drinks – 0 points

How often do you have caffeine, and how much?

If you rely on your morning cup of coffee or tea, you probably know that caffeine makes your brain feel good. And, in fact, some caffeine may indeed protect our brains from decline, at least for some types of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

People can vary in their ability to process caffeine, so any benefits of caffeine may not apply to everyone. Still coffee and tea may have other health-promoting substances.

On the other hand, a heavy caffeine habit may also signal underlying stress or overwork issues, which can negate any potential benefit. Past a certain point, more is not better.

How often do you habitually drink coffee, tea, energy drinks, and/or ingest any other forms of caffeine (such as caffeine pills)?

- A few times a week or less – 1 point

- Once daily or less – 2 points

- 2-3 times daily – 3 points

- 4 or more times daily – 1 point

Have you ever been genetically tested for your caffeine metabolism?

Research suggests that those people who are genetically “slow metabolizers” of caffeine may have health problems if they consume too much caffeine.

- Yes, and I’m a “fast metabolizer” – 2 points

- Yes, and I’m a “slow metabolizer” so I keep my caffeine intake moderate – 2 points

- Yes, and I’m a “slow metabolizer”, but I still have a fair bit of caffeine – 1 point

- No, never – Cool, it’s a thing you can do if you want

How do you deal with stress?

While our brains like and need a little bit of “good stress”, chronic and/or severe “bad stress” is hard on our brains. Over time, prolonged distress and anxiety can interfere with learning, memory, decision-making and other cognitive functions.

How do you manage stress?

Give yourself one point for each of these.

(Of course, other forms of stress management and self-regulation are also good; feel free to add your own items to this list.)

- I have a regular mindfulness / meditation / self-relaxation practice – 1 point

- I get outside with fresh air and nature – 1 point

- I laugh – 1 point

- I get together with friends and/or family – 1 point

- I spend time with animals – 1 point

- I exercise vigorously – 1 point

- I do yoga, tai chi, or some other purposefully relaxing exercise – 1 point

- I hit the pool, hot tub, spa, or sauna – 1 point

- I drink a bottle of wine – 0 points, just seeing if you’re paying attention

Part 4: What’s around you?

What are you exposed to?

Metals (e.g., mercury, lead, cadmium, aluminum), and other compounds (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls, pesticides, arsenic) can accumulate in the body and contribute to neurological problems. It’s unknown exactly what role they may play long term with Alzheimer’s development, but given their other known neurotoxic effects, it’s probably best to avoid them as much as you can.

Do you work in a workplace where you are exposed to harmful chemicals, such as cleaning products, pesticides / lawn chemicals, paint fumes, heavy metals such as mercury, etc.?

- No – 3 points

- Yes, occasionally – 2 points

- Yes, often – 1 point

In your daily household environment, are you exposed to harmful chemicals, such as cleaning products, pesticides / lawn chemicals, paint fumes, heavy metals such as mercury, etc.?

- No – 3 points

- Yes, occasionally – 2 points

- Yes, often – 1 point

How engaged are you in learning and life?

Our brains, like muscles, work better the more we use them. This includes learning, social engagement, and finding a sense of purpose in what we do.

Do you have hobbies, take classes, or otherwise do some purposeful, meaningful skill practice and/or learning — especially learning that actually feels challenging?

- Yes – 3 points

- No – 1 point

Do you volunteer, purposefully work to help others (such as animals, people, the environment, etc.), and/or contribute socially in some way?

- Yes – 3 points

- No – 1 point

Do you feel “connected” to life? Are you engaged and interested in what’s around you, other people, the world, and your own experiences?

- Yes – 3 points

- No – 1 point

How’s your social support?

Do you have close, supportive, meaningful relationships in your life (with people and/or animals)?

- Yes, I feel connected to others and supported by them – 3 points

- Sort of, I have some that are OK – 2 points

- I have some, but they aren’t close – 1 point

- I feel alone and disconnected from others – 0 points

What’s your total score?

| 0-29 | You might be struggling with implementing healthy behaviors, which might be increasing your risk for neurodegenerative diseases. Consider getting support to make some positive changes. |

| 30-56 | You have some healthy behaviors, but may want to improve a few of your lifestyle factors to increase your chances. |

| 57-84 | You have a solid set of consistent, health-promoting behaviors. Good for you! |

| 85 or higher | You are a brain health super star! |

What about some “extra credit” items?

We’ve covered the basics above. What if you want to be a brain health keener? What else could you do?

Ketogenic diets

Ketogenic diets have shown promise for treating some types of brain and mental health conditions, such as epilepsy. While this potential is exciting, we don’t yet know how it affects Alzheimer’s specifically.

Still, based on some short term animal and human data, it looks like ketogenic diets may benefit the hippocampus and may also help to minimize AGE production in the body. Ketones might offer protection in the brain against beta-amyloid accumulation.

Stay tuned for more research in this area.

Fasting / calorie restriction

Like ketogenic diets, the potential here is exciting. (Well, if fasting is exciting to you.) Our earlier research on fasting does suggest that it can lower inflammation and oxidation (two key factors in neurodegeneration and aging).

But, also like ketogenic diets, we can’t yet say for sure whether this matters.

Individual nutrients / supplements

Although many compounds and supplements look promising in vitro (i.e. in a petri dish), they don’t always work out in vivo (i.e. in real life).

This is, in part, because bodies are complex and have many regulatory feedback mechanisms that may prevent supplements from intervening too much in carefully controlled biological processes.

Or, too much of one thing from a supplement might knock out other processes elsewhere (which can be bad). It may also reflect the fact that we don’t necessarily digest, absorb, and/or use all that we eat.

But here are some nutrients and various compounds that may play a role.

It may be potentially beneficial to consume more of the following:

- Alpha-lipoic acid might slow cognitive decline in those with existing impairment from Alzheimer’s.

- Carnitine might play a role in the protection against cognitive decline. But carnitine has mixed results, and potentially harmful outcomes in regard to other chronic diseases (like heart disease). So stay tuned on this one.

- Choline and uridine are necessary for synapse formation. Some folks have a genetic variation that decreases their ability to form choline in the body, and thus increases their dietary choline requirements. Choline (and DHA) might explain why moderate egg intake seems beneficial to brain health. Choline, as citicoline in supplement form, might help improve symptoms of Alzheimer’s in those who are already in the early stages.

- Selenium is a useful antioxidant, and having a healthy selenium status is likely a good idea for brain health. Since selenium can build up quickly and lead to potential toxicity, best sources are foods like Brazil nuts rather than supplements.

- Zinc levels seem to be lower in the CSF and brain in those with Alzheimer’s. Probably best to get this from our diets, though, as too-high zinc consumption can interfere with copper metabolism.

It may be a good idea to consume less of the following:

- Copper, which can be found in beta-amyloid plaques, and interacts with APOE4 and homocysteine. Exposure to too much copper (generally from inorganic sources like pipes and certain supplements, since the liver processes copper from food appropriately) may contribute to neurodegeneration. In mice, too much copper seems to hinder the clearance of beta-amyloid.

- Iron is critical for brain development early in life, but it’s probably best to avoid excess iron with age, especially if you’re not a woman who menstruates (and thus has a mechanism to disperse excess iron). If you don’t need iron, don’t supplement it, and go easy on iron-rich meats, which are easily absorbed into the body. Iron appears to influence amyloid precursor protein (and when this protein isn’t processing efficiently, you have more beta-amyloid buildup in the brain).

- Ginkgo biloba has long been touted as a supplement to improve cognitive function. While it does appear to be safe, and might offer day-to-day benefits such as improved attention or mood, in terms of staving off Alzheimer’s disease, a Cochrane review in 2009 indicated that it doesn’t appear to be useful. Other studies since then confirm this. Verdict: Not a preventative measure for Alzheimer’s.

What should you do next?

Some tips from Precision Nutrition.

Start today.

Once Alzheimer’s has progressed, and neurons have been damaged or destroyed, it can’t really be reversed. However, most of us can take steps now to protect our brains and help lower our risk of neurodegenerative disease.

Recognize that this is a complex phenomenon.

There are many factors that go into developing Alzheimer’s. It’s not as simple as having the “wrong” genes or eating the “right” foods.

Recognize that your brain is part of your body.

Physical health includes brain health. Anything you do to improve your physical health will probably benefit your brain.

That includes:

- not smoking

- drinking in moderation

- getting your colorful fruits and veggies

- getting enough lean protein

- getting enough healthy fats

- eating as wide a variety of foods as possible

- getting regular exercise

- managing your stress

- being careful about chemical exposure

Recognize that brain health is also about emotional and psychological health.

Having social support and rewarding relationships; pursuing learning and growth; having a purpose in life — all of these are part of an overall wellness plan, and crucial for brain health as well.

If you learn, challenge yourself.

We often tend to repeat what we know. For instance, we might have done crossword puzzles for a few decades. It might feel “hard”, but you’re not actually learning. The same is true of many types of “brain games”, whose usefulness isn’t fully supported by evidence.

For neuroplasticity to occur and us to groove new brain pathways, we have to be truly challenged, perhaps even uncomfortable, during the learning process.

In particular, consider a new form of movement, a new language, and/or a new hands-on skill. All of these require you to integrate thinking, learning, verbal and nonverbal skills, visual and other sensory inputs, and kinesthetic (movement-based) information.

Use your quiz answers as data.

What’s going well? What health habits do you already have locked down?

Which health habits might you like to improve?

Don’t beat yourself up for a score that isn’t as high as you’d like, and don’t try to be “perfect”.

Instead, consider using the data to set some realistic, manageable long-term goals for changing your behaviors and habits.

Before you look for supplements or special solutions, get the basics in place first.

Yes, some supplements are promising. Yes, some “superfoods” may seem exciting. And if you truly like goji berries or turmeric lattes, enjoy them.

But in reality, your brain will probably be much happier about getting 8 solid hours of sleep every night than some magical bean from the Amazon rainforest.

Get help if you need it.

If your quiz answers revealed that you might need some extra support making healthy changes (such as getting to a healthy body weight; improving your regular exercise habits; and/or choosing foods that add value to your body), consider finding a good coach.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification.

Share