Borrowed from the bodybuilding world, reverse dieting can, at first, sound like the stuff of internet legends: Eat more food without gaining weight.

Too good to be true, right?

Maybe not.

What is reverse dieting?

Reverse dieting is a method that involves slowly and strategically increasing daily food intake, all in an effort to raise your metabolism. And while reverse dieting might seem like a one-way street toward weight regain, the technique actually offers a lot of promise—when done right.

Many people gain muscle and lose fat, all while eating more food than they were before.

But how does reverse dieting work, and is it right for you (or your clients)?

Let’s explore.

(If you want to see PN director of nutrition, Brian St. Pierre, MS, RD discuss this article, check out the video below.)

Generally, we don’t recommend eating like a bodybuilder.

All the macro counting, weighing and measuring, restrictive food options, and precise nutrient timing… it just doesn’t make sense for most people.

In fact, the diets many bodybuilders use to get competition-lean aren’t even sustainable for bodybuilders.

(Want the hottest nutrition, health, and coaching strategies delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for our FREE weekly newsletter, The Smartest Coach in the Room.)

For weeks leading up to a competition, bodybuilders follow super restrictive diets, which gets them abs you could grate cheese on, but has the unfortunate side effect of slowing their metabolisms. (We’ll explain why a little later.)

If they tried to maintain this approach after competitions, the hunger would eventually become overwhelming. Competitive bodybuilders also usually try to pack on as much muscle as they can during the offseason, and that’s nearly impossible when you’re on a low-calorie diet.

But like everyone else, when bodybuilders gorge on all the food they want, they add plenty of fat to go with that muscle.

The alternative: reverse dieting.

Smart bodybuilders slowly reverse their pre-competition diet by strategically and incrementally increasing their portions, an approach first popularized by Layne Norton, PhD.1

Basically, they reverse the steps they took to get competition ready, one nutritional step at a time. And they also usually gradually reduce cardio and focus on strength training.

This allows their metabolism to adjust upward over time. (Again, we’ll go deeper into metabolism in a moment.)

Eventually, they hit a calorie intake where they feel energized, are performing well in the gym, and are gaining some muscle—all while minimizing fat gain.

This doesn’t mean zero fat gain, mind you, and the use of PEDs, or performance-enhancing drugs, is also a factor.

But reverse dieting can leave them in a much better position to compete again in the future—compared to following a “see-food” diet that dramatically balloons their body fat percentage.

And if they never want to compete again? That’s fine too because they’re back to eating a normal and sustainable amount of food.

Reverse dieting may be the exception to our “avoid bodybuilding diets” rule.

You can see how reverse dieting might apply to the general population.

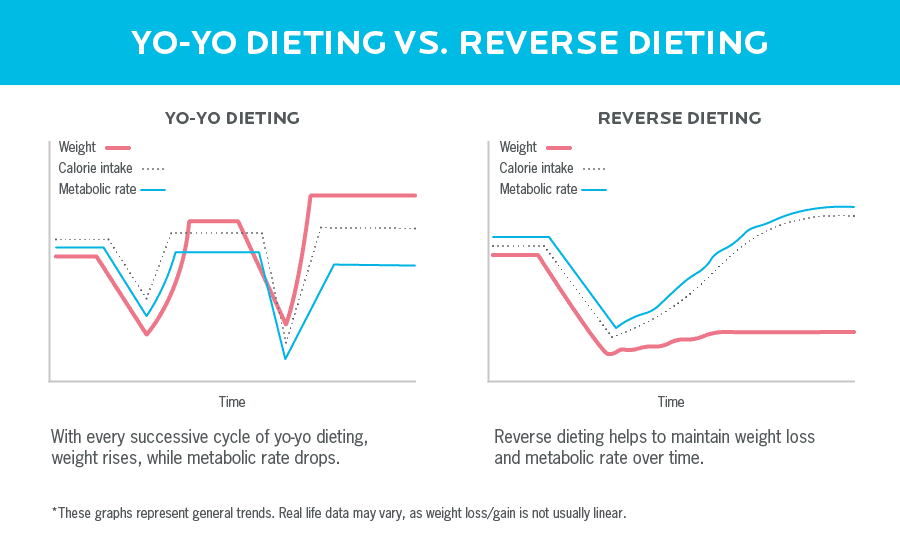

Weight loss is notoriously difficult to maintain. Most people end up regaining what they lost, and sometimes more.2

Why? For many reasons, but here’s just one: When you reduce calories and your body size shrinks, your metabolism eventually slows.

That means you must cut more calories to keep the fat loss going.

And all too often, by the time someone reaches their goal, the amount of calories they can eat to maintain their weight doesn’t translate to a lot of food. It feels paltry and incredibly difficult to stick to.

As a result, additional calories creep back in and the number on the scale starts to rise.

So they diet again.

And on the yo-yo cycle goes.

But if instead they slowly, intentionally, and strategically add the right number of calories over time, they’ll be more likely to maintain their fat loss long-term.

How does reverse dieting work?

We know. We know. This all probably sounds a little hocus pocus abracadabra. Bear with us. There’s some science to back this all up, but before we can dive in, we need to cover the concept of energy balance.

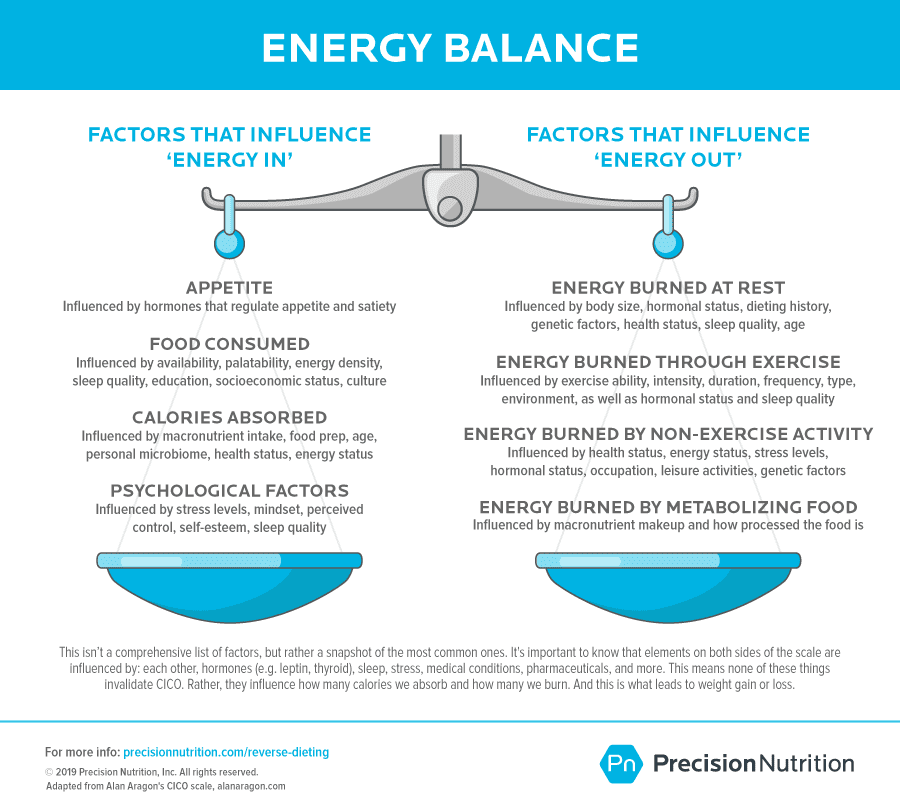

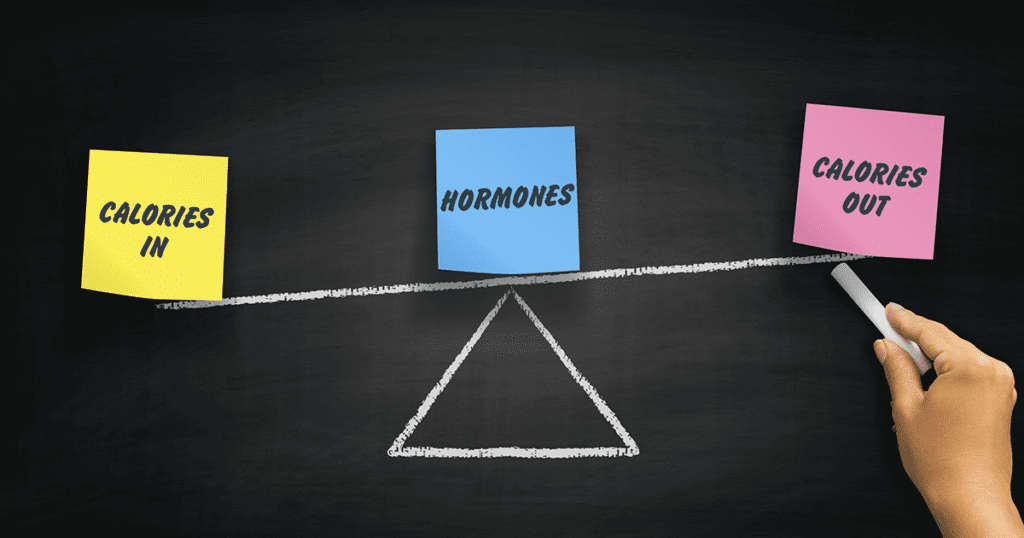

Simply put:

- When you eat more energy (calories) than you burn, you gain weight.

- When you eat less energy than you burn, you lose weight.

Many people know this concept by another name: calories in, calories out (CICO).

Some people debate whether CICO and energy balance are valid, but only because they misunderstand a key point.

The energy balance equation is simple, but, as you can see below, many factors affect energy in and energy out.

These factors go way beyond food and exercise. Factors people often overlook—food absorption, stress, genetics, and metabolic adaptation (described below)—have the potential to tip the energy balance “scale” in either direction.

Reverse dieting seems to work through one of the factors that can impact energy balance: metabolic adaptation.

One type of metabolic adaptation is known as the body’s “starvation response.” (This is different from the fabled “starvation mode,” by the way, which isn’t really a thing.)

Obesity is a global health issue now, but it wasn’t always that way. Starvation, on the other hand, has been a very real threat to humankind for hundreds of thousands of years.

So when you eat less, your body instinctively starts preparing for famine in several ways:

- Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) declines. That’s the amount of energy you need to live when at rest. This reduces energy out.

- Exercise becomes more difficult because you have less available energy. (If you’ve ever tried to do an intense workout on a low-calorie diet, you know what we’re talking about.) So you’re likely to burn fewer calories through activity.

- You also expend less energy through exercise because, as your body gets smaller, it doesn’t require as much fuel—and your metabolism also adapts to make you more efficient. This also reduces the number of calories you burn through movement, resulting in less energy out.

- Daily activity outside of workouts (think: pacing while you’re on a phone call, walking to your car, fidgeting) lessens, resulting in reduced energy out from non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT).3

- Digestion slows, so your body can absorb as many nutrients as possible. This increases energy in.

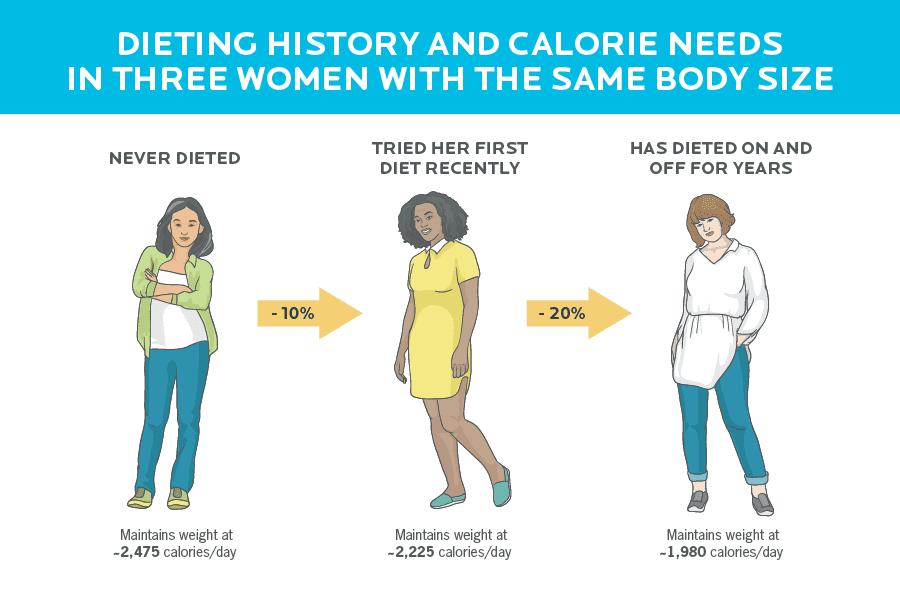

Because of this adaptive response, someone who has dieted down may need 5 to 15 percent fewer calories per day to maintain the same weight and physical activity level as someone who has always been that weight.4

And if someone’s lost an extreme amount of weight? The percent drop in calorie needs becomes more extreme, too.5

(Hey, no one ever said diets were fair).

The silver lining?

Metabolic adaptation works both ways.

If you increase your calories gradually, your body will adapt in the other direction. This phenomenon is known as adaptive thermogenesis, which basically means your body wastes calories as heat.

When done properly, reverse dieting provides several metabolic benefits:

- BMR rises, resulting in more energy out.

- Workout capacity increases thanks to more available energy, increasing energy out.

- NEAT increases for the same reason, resulting in more energy out.

- Digestion returns to normal, so your GI tract is no longer squeezing every bit of sustenance from every morsel, decreasing energy in.

Pretty cool, right?

But in order to get this effect, it’s important to add calories slowly. That’s primarily because the body seems to respond differently to varying rates of “overfeeding.” (That’s the word researchers use to describe eating beyond your calorie needs.)

In one study, eating 20 percent above maintenance calories did not significantly increase fat gain, whereas eating 40 to 60 percent above maintenance did.6

In other words, if you maintain your weight on a 2000-calorie diet, you might be able to eat up to 400 extra calories a day without seeing a big impact on the scale.

But an extra 800 daily calories? It’s probably going to weigh you down.

Additionally, some data suggest that the time people need to “recover” from dieting is roughly proportional to the amount of time they spent dieting.7

So if you restrict calories for six months, you may need to give your metabolism six months to adjust.

This is just one of the many reasons…

Reverse dieting isn’t magical.

Reverse dieting has gained miracle status in some corners of the internet as a way to eat more to lose weight.

That makes it seem like reverse dieting flies in the face of the energy balance equation and the laws of thermodynamics. This is not the case.

Can you lose weight while reverse dieting? Yes.

But it’s still always because increased “energy in” results in increased “energy out.”

In our experience, reverse dieting can absolutely work—but not for everyone, in the same way, in all conditions, 100 percent of the time.

There are three important caveats to acknowledge here.

Caveat #1: There are no guarantees.

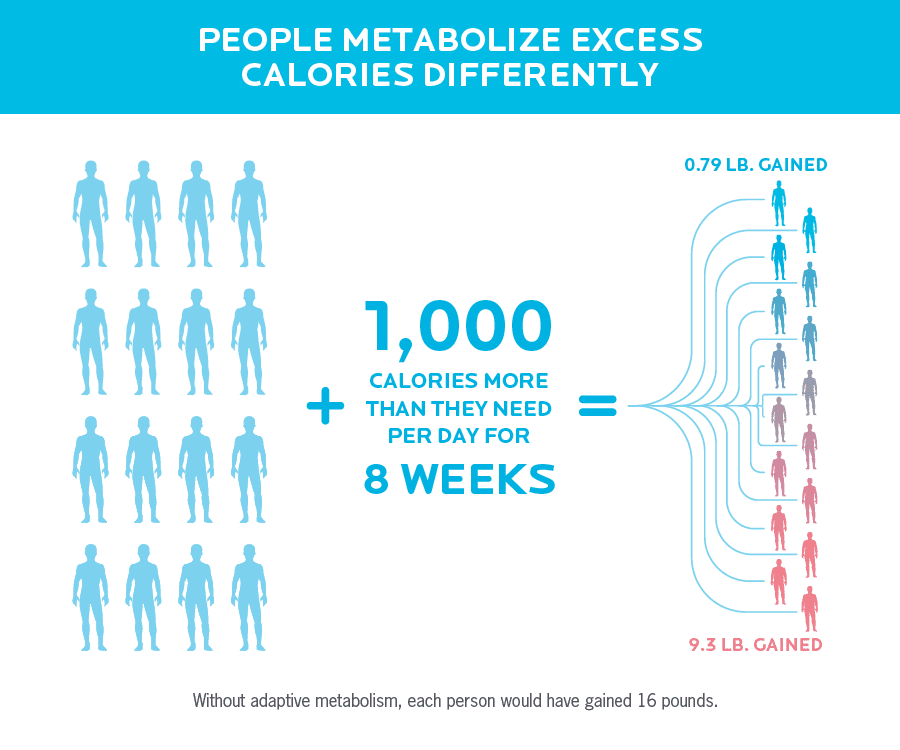

As much as we’d like to think people are spreadsheets and that all of this comes down to simple math, there’s much variability from person to person.

Here’s an example: In one study conducted at the Mayo Clinic, researchers brought 16 normal-weight people into a lab for eight weeks. They served them huge meals that provided 1,000 extra calories each day.

That’s the equivalent of eating about two double cheeseburgers a day on top of your usual noshing. Plus, the participants were instructed not to exercise.8

If you do calorie math, everyone should have gained 16 pounds in eight weeks.

In reality, they gained anywhere from under one pound to about nine pounds.

The biggest predictor of adaptation, or gaining less weight? Increased NEAT.

Some people’s bumped up majorly, and their weight barely changed. Others had much more modest increases, and they ended up gaining more.

In reverse dieting, the hope is that your body and metabolism will adjust via NEAT and other mechanisms. But the degree of adjustment—and whether any adjustment happens at all—varies from person to person.

Plus…

Caveat #2: Age affects our ability to adapt.

“Wow, I can keep eating more and more and never gain weight?!” said no post-menopausal woman ever.

All jokes aside, metabolism naturally declines with age.

Unless you strength train consistently, you lose five to 10 pounds of metabolically active muscle per decade starting when you’re 25 to 30.9

That continues in a pretty linear fashion.

So the same reverse dieting protocol that worked for a 20 year old isn’t going to work in the same way when they’re 40 or 65.

Caveat #3: Reverse dieting assumes you’re reasonably sure of your calorie intake.

We say reasonably sure because calorie counting is imprecise.

There’s no way to be 100 percent sure of your calorie intake outside of a lab. So the goal is to have a good enough gauge on how much you can currently eat without gaining.

That’s because reverse dieting requires very small changes in calorie intake over time. Often as few as 50 to 100 calories a day. That’s the difference of approximately 0.5 to 1 tablespoon of peanut butter, for reference.

It’s basically impossible to hit those numbers exactly. But anyone who counts calories, macros, and/or hand portions is going to do a much better job than someone who eyeballs it.

Consistency also matters. It’s possible that someone who eats more calories some days than others would be able to reverse diet. But it’d be pretty difficult to get that slow, steady increase in energy needed to do it properly.

To be clear, reverse dieting is a somewhat advanced method.

In order to do it effectively, you need to be willing to:

- eat roughly the same amount of food each day.

- measure your food intake.

- adjust your physical activity up or down, depending on your goals.

- acknowledge that it may not work for you.

3 situations ideal for reverse dieting

Caveats notwithstanding, reverse dieting might be a good approach in three specific situations.

Situation #1: “I want to eat more without gaining weight.”

We’ve already covered this one. Gradually increasing calorie intake can help to turn up the metabolic heat for people who’ve slashed calories to get the scale to go down.

But can the technique work for non-dieters?

Say someone just wants to be able to enjoy social situations, needs more nutrients for health and performance, and/or wouldn’t mind welcoming more calorie-dense foods (think: avocado, nut butters, coconut cream, the occasional donut) into their lives?

For those people, reverse dieting probably won’t work as effectively as it would for someone whose metabolism has slowed due to long-term dieting.

There are limits to how much metabolism can heat up and cool down. If someone is already pretty metabolically healthy, there’s (theoretically) less room to shift up.

The takeaway: If someone’s been dieting for a long time and is ready to maintain their current level of body fat, reverse dieting can help increase maintenance calories, resulting in a more sustainable way of eating long-term.

Situation #2: “I’m eating 1,200 calories a day and not losing weight.”

Let’s get one thing out of the way: A lot of times, when someone says they’re eating 1,200 calories and not losing weight, they’re not actually eating 1,200 calories. Usually they’re not estimating their calorie intake effectively.

A highly restrictive diet that keeps calories genuinely low for a few days can increase the chance of accidentally overeating on other days. That’s because our brains evolved to nudge our behavior toward survival, not Instagram glory. (To read more about this, check out this article.)

The occasional highs average out the steadier lows.

By the end of the week, once you factor in the snacks, weekend drinks, and extra hidden calories, intake may actually average out to maintenance level.

You just don’t notice it because you’re paying attention to the few days when you really did hit those low calorie numbers.

So, to be clear, in this situation, for reverse dieting to work, you or your client must truly be subsisting on very few calories and have reached that “bottoming out” point. This is the point where you don’t feel like you can reduce your calories any more.

Provided you’re already eating mostly high-quality, whole foods, reverse dieting could be really helpful.

(If you’re not already eating high-quality foods, try that first. Read this article to learn more.)

The reasoning here is pretty simple.

Slowly increasing calorie intake can help restore metabolic output.

That means, to some degree, side-stepping the adaptations that come along with a history of dieting.

But to give your metabolism the time it needs to adapt, you’ll want to stay at a higher calorie intake for roughly as long as you spent dieting. Then, after several months of maintaining, that person can start restricting calories again and see the scale start to move.

The takeaway: If you’re truly eating a super low-calorie intake and the scale is stuck, reverse dieting might restore metabolism enough to jumpstart fat loss.

The more likely outcome, however, is this: It allows you to take a break from dieting, without gaining weight, as well as bring much-needed pleasure back into your eating life.

Then, once you’ve psychologically and metabolically adjusted, you can return to dieting and success.

Situation #3: “I want to get ripped.”

Another common use for reverse dieting: to improve body composition. So in other words, losing fat, gaining muscle, and remaining about the same weight.

Interestingly, Precision Nutrition’s co-founder, John Berardi, Ph.D., came up with a similar idea years ago, called G-Flux, also known as “energy flux.”

He observed that highly active people who consume more calories typically have less fat and more muscle. For example, professional athletes tend to eat a lot, exercise a lot, and remain very lean.

G-Flux is similar to reverse dieting, with one key difference.

When bodybuilders reverse diet, they usually dial down their cardio (although not always), while G-Flux assumes you’ll be doing more than before. The G-Flux version tends to work more effectively for muscle gain than the bodybuilding-style approach. Here’s why.

Reason #1: More cardio will help increase your energy out, giving you more flexibility with energy in.

Reason #2: Increased exercise also changes nutrient partitioning, sending more calories toward muscle growth and fewer to your fat cells.

Plus, since you’re eating more food, you have more opportunities to get the quantities of vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients you need in order to feel your best.

The takeaway: Provided you have the ability to exercise more than you are now, increasing calories while keeping activity high is a solid strategy for muscle growth.

How to reverse diet in 5 steps

Step 1: Choose your tracking method.

You’ll need a method to track your food intake.

If you’ve been eating in a calorie deficit, you’re likely already using one. If it’s working for you, stick with it. If not, consider switching it up with these options.

Option #1: Calorie and macro tracking

Calorie and macro tracking are the most precise methods available outside of a lab, which makes them a logical choice for the small increases reverse dieting requires. (You can calculate your reverse diet macros using our handy macros calculator here.)

But many people find calorie and macro tracking to be labor-intensive and frankly, unenjoyable. If that describes you, consider option two.

Option #2: Hand portions

In this system—developed by Precision Nutrition—you use your hand as a personalized, portable portioning tool. And because each hand portion roughly correlates to a certain number of calories as well as protein, carbs, or fat grams, this method counts calories and macros for you.

Hand portions aren’t as accurate as counting calories and macros, but they’re accurate enough. (Specifically, 95 to 98 percent as accurate, based on our internal research.) And that’s all that matters for reverse dieting.

(For an in-depth breakdown of the methods you can use to track your intake, read this article.)

Step 2: Determine your maintenance calories.

Before you can increase calories, you need to figure out your maintenance intake, which is what you currently can eat to maintain your weight.

If you already know this, great.

If not, use our free Nutrition Calculator. It’s the most comprehensive calorie, portion and macro calculator available and is based on NIH mathematical models for bodyweight planning.

Select “improve health” as your goal and enter the rest of your personal details. The calculator will suggest calorie, macro, and hand portions close to your maintenance intake.

Before adding calories, experiment with your maintenance intake for 2 to 4 weeks, monitoring whether you gain, lose, or maintain. This will help you personalize what the calculator recommends.

Our nutrition calculator is pretty freaking awesome, but no calculator can take your dieting history, genetics, and other qualitative factors into account. Only experimentation can do that.

Step 3: Decide on your macronutrient balance.

It can be easy to get caught up in the ideal macro ratio for your reverse diet.

But the truth is, the most important macro for reverse dieting is protein.

A higher protein diet seems to maximize muscle protein synthesis and minimize protein breakdown, which should lead to more muscle gain. This is probably one of the reasons higher protein diets are better for improving body composition than moderate or low protein diets.10,11

More protein also helps increase energy out because your body uses more energy to process protein than it does for carbohydrates and fat.

Our recommendations for optimal protein intake for building and maintaining muscle range from:

- 1.3 to 3 g/kg (0.6 to 1.35 g/lb) for women

- 1.4 to 3.3 g/kg (0.65 to 1.5 g/lb) for men

Those aiming to maintain lean mass while losing body fat should shoot for the higher ends of those ranges.

As for carbohydrates and fats, the balance between the two isn’t so important. People can lose weight and/or gain muscle with any reasonable mix, as long as it’s sustainable.

So decide your carbohydrate and fat ratio based on how you like to eat and what you can imagine yourself doing long-term.

We could walk you through a pretty complicated set of instructions that would show you how to do the calorie math by hand—or you could just use our Nutrition Calculator.

Once the calculator estimates your calorie and macronutrient needs, it automatically converts those numbers into food portions you can gauge with your hands.

The result: You can skip weighing and measuring your food, as well as logging the details of every meal into calorie and macro tracking apps.

Reverse dieting requires accurate measures of food intake over time, and the small changes necessary to make it work can easily get lost in the noise. Using the calculator makes this process much easier and more reliable, so you’re more likely to be successful.

Step 4: Choose your rate of progression.

Your goal—what you hope to achieve by reverse dieting—determines how many calories you add each time you increase your intake. And how often you do add calories will depend on the metrics you track. (More on that in Step 5.)

It’s also helpful to consider how motivated you are to eat more food as well as how much fat you’re willing to gain.

Depending on your situation and preferences, you’ll choose one of the three approaches described below.

In the chart, you’ll probably notice that each calorie bump comes from either carbs or fats. That’s because you’ll keep your protein intake constant throughout your reverse diet, based on what you determined in step 3.

Step 5: Monitor your progress and adjust as needed.

Once you’ve picked your plan, it’s time to get started.

To determine whether a reverse diet is doing what you want it to do, track key metrics along the way. You might:

- Weigh yourself daily or weekly. (The day-to-day numbers aren’t so important, but keeping record of your average weekly weight gain or loss is useful)

- Measure your waist, hips, and other body areas, which may reflect changes in body composition better than the scale

- Snap progress photos, which also may reflect changes in body composition better your scale

- Gauge workout performance through heart rate monitoring, personal bests, or other metrics that are meaningful in your sport

- Track energy levels, hunger, and digestive symptoms, and any other subjective measures that are important to you

Based on the data you continually collect, adjust as needed.

Some people may find they’re able to up their intake every week without gaining much fat. Others may need to space out increases over longer intervals.

Increasing every two to four weeks is a solid guideline for most people.

How do you know when to stop reverse dieting? It depends on your goals. A successful reverse diet can take anywhere from a few weeks to many months.

Some signs you may want to continue with your reverse diet include:

- You haven’t gained much fat, or you don’t mind the amount you’ve gained.

- You still feel interested in eating more than you are currently.

- You’ve been reverse dieting for less time than you were in a calorie deficit.

Signs it may be time to stop your reverse diet include:

- You’ve gained as much fat as you feel comfortable gaining.

- You don’t feel interested in eating even more.

- You’ve been reverse dieting for longer than you were in a calorie deficit.

Because reverse dieting requires a bit of experimentation to get right, many people find that their final calorie increase leads to more fat gain than they’re comfortable with.

By tracking metrics, you can catch that early, adjust your calories down one notch, and find your sweet spot (where you can maintain your weight while eating a comfortable amount of food).

Life after reverse dieting

So what happens next?

Reverse dieting is a tool for a specific job—one that requires quite a bit of effort and attention.

Once the job’s done, it’s time to move on.

After closely monitoring how much you eat using external methods—such as calorie, macro-, or hand-portion tracking—consider taking some time to focus on internal methods of regulation, like eating slowly and mindfully.

That doesn’t mean you can’t ever come back to reverse dieting, though.

In fact, you can use reverse dieting as a tool anytime you cut calories for a while. It’s helpful to gradually ramp them back up for all the benefits we covered in this article.

But remember: Despite what you may have seen on social media, it’s key to approach reverse dieting from a realistic perspective and understand when and how it can be used most effectively.

After all, reverse dieting is based on biology—not magic.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a health and fitness pro…

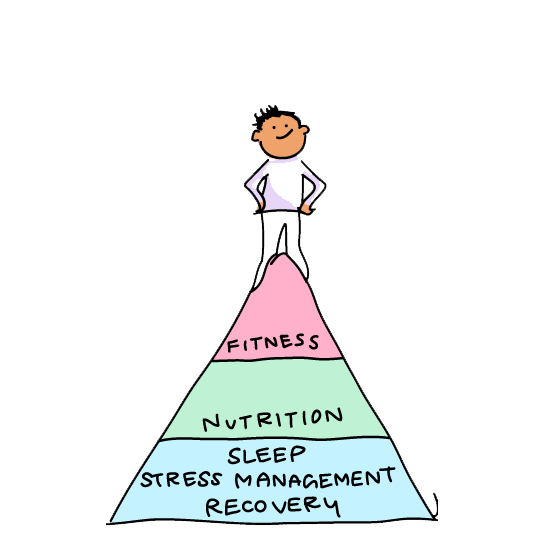

When your clients are stressed and exhausted, everything else becomes a struggle: going to the gym, choosing healthy foods, and managing cravings.

But with the right tools, you can help your clients overcome obstacles like chronic stress and poor sleep—leading them toward the lasting health transformations they’ve always wanted.

PN’s Level 1 Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery (SSR) Coaching Certification will give you these tools. And it’ll give you confidence and credibility as a specialized coach who can solve the biggest problems blocking any clients’ progress. (You can join the SSR Early Access List for our biggest discount + exclusive perks.)

Share