In Part 3 of this article series, we look at back-of-package labeling: nutritional information and ingredients.

In particular, we look at how calorie counts don’t accurately reflect how our bodies process food. And we challenge the classic “calorie math” of “energy in versus energy out”.

Problems with back-of-package labeling

In part 2 of this series, we looked at “front-of-package” (FOP) labeling. Generally, FOP labeling can be a little more dodgy – manufacturers can use tricky language, suggestive images, or claims from various organizations to make you think certain foods are better than others.

Although back-of-package labeling, or nutritional information/ingredients, is more tightly regulated by law, it has its own challenges.

Problem: People often find standards confusing.

What is an RDA (Recommended Daily Allowance) and how does it relate to a DV (Daily Value)? A DI (Dietary Intake)? A General Dietary Allowance (GDA)?

If we see “20% of DV for calcium” on a package, does the DV mean:

- Get enough calcium? or

- This is a baseline for calcium that prevents you from dying – you should probably get more? or

- For heaven’s sake, don’t eat more calcium than the DV or your eyeballs will explode?

Consumers are often confused by these kinds of puzzling labels.

For example, one study found that many people mix up DV with ingredients – so, they assumed that a product that has 10% of the DV for calcium was actually made of 10% calcium.

Problem: It’s often hard for consumers to understand and contextualize information that is relative.

In other words, what about foods that are “high in X” or “low in Y”? Should I eat “high in X” sometimes? Never? Always? How high is high?

Is this food higher in X than that food? If something has 50% of the RDA/DV/DI/GDA or whatever for X… is that good?

Problem: Just because a nutrient is in a food doesn’t mean it’s “natural” or “good for you”.

For example, many products advertise that they’re “high in fiber”. The back-of-package label will show a higher fiber content.

However, the fiber has been added. The original food processing has stripped the good stuff out, so manufacturers must add it back in.

And the added nutrient might not be the same as the real thing.

For instance, many of the B vitamins that “fortify” things like cereals are actually derived from coal tar and other petrochemicals. The fiber may come from wood pulp or highly processed, solvent-extracted plant roots.

It’s hard to argue that this is better than (or nearly as good as) naturally occurring B vitamins or fiber in whole foods.

As a matter of fact, in the Netherlands, food regulators don’t believe it. They’ve decided that for any foods labeled as “high-fiber”, the source of fiber must come from the actual ingredients of the food itself.

What do the label numbers mean for our bodies?

“The relatively recent focus on nutrients parallels an increasing discrepancy between theory and practice: the greater the focus on nutrients, the less healthful foods have become.”

– Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH & David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD

These days, almost everyone understands the idea of calories as a measure of energy.

But for most of human history, calorie counting (and nutrition science) didn’t exist.

The “calorie” was first defined by physicist Nicolas Clément in 1824 as a unit of heat (from the Latin root calor, or “heat”). One “calorie” is the energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1 °C.

The “calories” we see on food packages are actually kilocalories (which you may see abbreviated as kcal). A kilocalorie is the energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 kilogram of water by 1 °C.

Many other countries use kilojoules instead of kilocalories to describe how much energy is in foods (so when traveling in Europe, don’t flip out when you see that something has 1480 kj – it’s actually 350 kcal).

For our purposes, we’ll use “calories” to refer to kilocalories. (Otherwise we’d be talking about apples having 95,000 calories, which can get kinda weird.)

Now, think about it: The calorie was “invented” by a physicist. What does that tell you about the value of food?

As you’ll see, our modern understanding of food was shaped by these findings in physics and chemistry.

For example, during the Great Depression and Second World War, governments became more and more concerned about malnutrition in both military troops and the general population. Thus, state agencies began to order that certain nutrients (including iron, iodine, vitamins B1, B3, D, A) be added to staple foods such as flour, milk, and cereals.

This is when nutrition science grew.

Interestingly, as we tend to focus more on the calories and nutrition science, we tend to focus less on food and how we eat.

A calorie from a Twinkie seems the same as a calorie from kale. Over-eating vegetables or chugging diet soda is OK because, well, the calorie damage is minimized… right?

And while many of us act like calorie tallying experts, data shows that few of us can accurately gauge how many we’re actually eating each day.

Do labels actually help us?

For many years it was hard to get any information from food companies and restaurants about nutrients/calories at all. Now, we probably have more information than we need (and we’re not sure whether that information is even useful or accurate).

But there are many other factors that affect how we process food. Nutrition labels capture only some of these factors.

The brain game

In Part 2, we looked at some of the ways in which front-of-package labeling can affect our buying decisions. Nutrition claims and labels can also have a profound influence on how we experience food… even on how full or satisfied we feel after eating.

For instance, research suggests that the stomach signals less satisfaction after eating “health food,” regardless of the actual fat and calories consumed. Conversely, when we eat foods we think are indulgent and “sinful”, we feel fuller and more gratified, even if the foods are much lower in calories.

Meanwhile, according to one survey, only 23% of Americans order the healthier restaurant options. (And that’s probably a generous estimate.)

Why? People say things like:

- Eating out is a treat.

- Healthy items cost more.

- I don’t want to feel like that “health nut” that orders “healthy” items when dining with others.

Calorie math FAIL

One reason that people give for not ordering healthier is a good one: They don’t believe healthy menu options are actually a smarter option.

And they may be correct: Researchers have discovered that restaurant food labels can be off by 100-300 calories. Some ingredients, such as mono- and diglycerides, which are also found in processed foods, aren’t counted towards calorie counts because they’re not technically triglycerides (aka fats).

Thus, what you see on a nutrition label (whether at a restaurant or a home) may not be completely accurate.

Sure, 100-300 calories may not be a huge deal for a one-time meal, but if you’re trying to count calories, and you have a few meals a day that are 200 calories off… well, that adds up. (Of course, this suggests that we should probably eat whole, unprocessed foods as often as possible.)

So, we’ve got a combination: We feel less satisfied after eating items labelled “healthy”, regardless of whether those items actually are healthy. And even when we try to eat “healthy” things… we might not be getting it right, thanks to the inaccuracies of labeling.

There are other problems too.

Calorie math vs. biological reality

We’ve all been taught that there are 3,500 calories in a pound of fat. This means if someone eats a 60 calorie cookie each day beyond what they need, they will gain 6 pounds in a year (and 60 pounds in a decade).

Errr, maybe not.

Equations in nutrition texts might not be as useful as we originally thought.

When researchers actually keep people in a lab to study food intake (not just relying on food diaries written in lipstick on the backs of napkins), they find that the body’s self-regulatory mechanisms temper the effects of small changes in diet and/or behavior.

In other words, your body is smarter than you. It’s a dynamic, adaptive, living organism. Not a machine.

Your body can “gear up” and “gear down” its energy use depending on a variety of factors such as hormones, metabolic functions (such as recovering from a hard training session), and perceived food availability.

Ever had the “meat sweats” after eating a big, protein-heavy meal? You’re experiencing the “thermic effect” of harder-to-digest foods. The body has to “gear up” and get things revving to accommodate this demand.

Or conversely, perhaps you’ve dieted hard for a long time, and find yourself cold, lacking energy and mojo. Your body’s “geared down” your metabolic functions to conserve energy.

Calorie values we read about are based on numbers obtained from incinerated food. (More on this below.) Yet our body doesn’t incinerate food, it digests food.

Digestion is an active process with innumerable moving parts (including trillions of bacteria that do much of the “digesting” part for us). It’s not just moving “calories” along a conveyor belt.

The way we digest food can change the amount of energy we can get from it by up to 25%. The more easily we can break down a given food, the higher the available energy, and vice versa.

That means our digestion can be affected by:

- Macronutrients and fiber: Protein, fiber and resistant starch don’t provide the same amount of energy to our body as when burned in a calorimeter.

- Processing: If a machine has chewed and manipulated the food for us, our mouth and gut don’t have to work much. White flour in a muffin is handled differently than al dente spelt berries. Processed food takes less energy to digest and absorb compared to whole foods.

- Cooking and heat processing: This often breaks down the stuff (such as fiber) that our digestive system might get hung up on, allowing us to get more energy out of a given food. One researcher thinks that cooked food may provide 25-50% more calories than raw food.

- Our GI tract health and flora: Our intestinal bacteria do much of the work of “digestion” for us. When our internal bacterial environment (aka our microbiome) changes, our ability to absorb nutrients changes.

For more see:

All About Raw Food

All About Resistant Starch

Food Processing: A Calorie Isn’t A Calorie

All About Preserved Produce

Calorie realities and paradoxes

While calorie counts on labels can give an idea of a food’s nutrient density (in other words, its energy relative to the other good stuff it contains, like vitamins or fibre), calorie counts can’t always tell us the full story.

There’s energy in and there’s energy out, but there’s a person in between.

We’re living organisms, not a lab

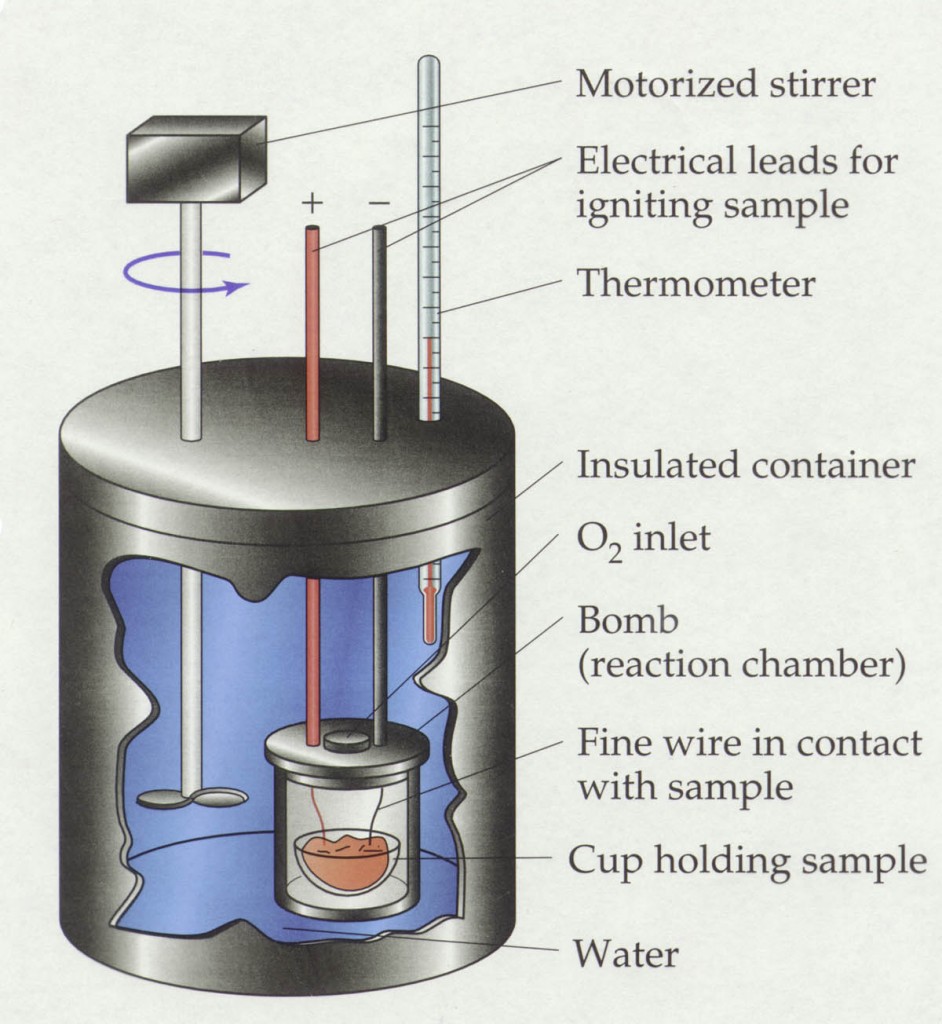

To figure out how much energy a given food contains, scientists burn food samples in a bomb calorimeter. This single result then becomes the standard value in calorie/nutrient databases.

The food analysis process includes:

- Weighing the food or meal

- Blending the food or meal until smooth with an even consistency

- Freeze drying the pureed mush

- Grinding the dried pureed mush into a fine powder

- Cooking the powder until it bursts into flames and all that’s left is a pile of ash

Now, after a spicy burrito or vindaloo, it might feel like stuff is bursting into flames in your stomach, but in general, our body handles food differently than this.

Our body responds to food differently based on the timing of our last meal, how much physical activity we get, our gut health and how much we chew the food.

Food varies

The food itself can also throw nutrient calculations off. This can include the following factors:

- Resistant starches/fibers: The human body doesn’t get as much energy from resistant starches/fibers.

- Data are old.

- Analytical methods are imprecise: Any analysis is only as good as the testing method. The way we test nutrients and calories doesn’t always provide reliable results.

- Product variety: Batches vary.

- Soil and growing conditions: Produce grown in nutrient-rich soil is different from produce grown in nutrient-depleted soil.

- Ripeness at time of harvest: Peaches or tomatoes picked at the peak of the season are different from those picked out of season.

- Animals’ diets: The nutrients/calories found in milk, meat, and eggs vary based on what the animal ate and how it lived.

- Length of storage: Do you think there is a difference between spinach harvested this morning and spinach harvest three weeks ago in a different time zone? There is.

- Preparation method: Eating raw kale leaves is different than boiling kale and then pureeing it into a soup. The amount of cooking and processing affects the amount of calories/nutrients we can get from the food.

- Cooking time: A one-minute steam is different than a 30 minute boil.

- Shrinkage or volume change during cooking: This varies from batch to batch.

The calorie number we see on the food label can have an error margin of +/- 25%. Frozen foods have been shown to contain 8% more calories than the package lists and (as we mentioned) restaurant meals can have up to 18% more calories than what they indicate.

Think about it. Even a small error margin of 10% can add up over time if you think you’re eating 2000 calories a day.

You don’t always know what you need

Consumers also lack context. For instance, although two-thirds of consumers say they look at calorie information specifically, they don’t know how it relates to them.

The vast majority – 88% – of consumers couldn’t accurately guess their daily caloric needs based on their age, weight, and height.

Even if we can understand the calorie information, and even if that calorie intake is more or less correct, we might judge our own intake wrongly.

Calorie paradoxes

Finally, there are so-called “calorie paradoxes” – situations where, officially, food energy seems higher… but the results aren’t what we might expect (if we follow the standard calorie math, that is).

For example, people who eat nuts and seeds regularly seem to weigh less than folks who don’t eat them. This is a calorie paradox: Nuts are extremely calorie dense.

Ah, but foods are more than just calories.

Nuts also seem to keep people feeling full longer, promote energy expenditure and/or inefficient energy utilization (in other words, fidgeting and moving around more), and have limited bio-accessibility in the gut (meaning that it’s harder for our GI tract to extract a lot of energy from them).

So, assuming you aren’t mindlessly snacking on the Club Pack of mixed nuts while watching a 2-hour movie, nuts can actually help you get and stay lean. Huh.

Another calorie paradox includes “free foods” like diet soda. Officially, these foods have few calories. But people who drink diet drinks seem to have the same risks of becoming fat and developing disease as folks consuming sugar-filled drinks.

Thus, the kind of foods we eat, rather than the precise calories we count, is a crucial piece of the puzzle. This goes against conventional wisdom in America of “eating things in moderation” and simply “eating fewer calories” without worrying about nutrition.

“The notion that it’s O.K. to eat everything in moderation is just an excuse to eat whatever you want.”

–Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian

Summary and action tips

- More information isn’t always better or more useful.

- Although it helps to know the nutrient and energy content of foods, nutrition labeling isn’t a perfect system. Calorie counts may be inaccurate or misleading, for example.

- Calories are a measure of heat. They don’t reflect what actually happens in our body. We don’t incinerate food; we digest it.

- Applying updated science and restructuring nutrition labels probably won’t solve the problem of fatness and disease, especially since people often compensate for things they think are “healthy” or “low-calorie” by eating more.

- If you want to get fitter, healthier, and leaner, move beyond calorie counting.

- Focus on the nutrient quality of the foods you eat.

- Shrink your portion sizes, eat until “just satisfied” rather than “stuffed”, and try to get a little hungrier between meals. You might even find that you need fewer meals than you think.

- Don’t worry about the numbers so much. They won’t help you as much as you expect.

To continue learning about food labels, check out part 4 of this article series where we talk about how you can be a more aware, critical consumer.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share