If you ski, jump, run, or skate, you’ve probably injured your knee, or know someone else who has. How can you keep yourself safe? Look behind you.

Have you ever pulled your hamstring, or worse, injured your knee?

Off to the physiotherapist you went. After some poking and prodding you were probably told you have a muscle imbalance because your hamstrings are too weak for your quads.

What does that really mean? Too weak? Muscle imbalance?

What if you stop doing any quad work? Then you could have weak quads that match your weak hamstrings – problem solved.

Why do hamstrings matter?

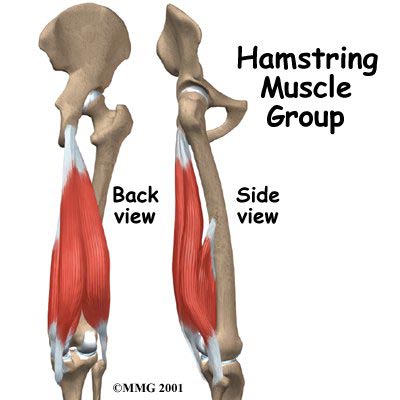

Hamstrings are useful things. They are biarticulate muscles that run along the back of your thigh, attaching at both the hip and the knee. They flex the knee and extend (straighten) the hips.

What we refer to as “a hamstring” is actually a four-part structure — more like a constellation of muscles that act in concert than a single muscle that plays solo. (More on hamstring anatomy)

These muscles are so useful that the phrase “hamstrung” has come into common use. It refers to the historic practice (found in places from Sudan to Mongolia to ancient Greece) of cutting the hamstring tendons so that a person or animal can no longer run away. Today it means simply being prevented from doing what you want to do. But nobody is “biceped” or “subscapularised” — the term implies the usefulness of those particular leg muscles.

When you pull your hamstring, say, running, what happens is as your knee straightens (as your quads contract) your hamstring lengthens. If your hamstrings are too weak then your quads pull your hamstring faster than it can lengthen.

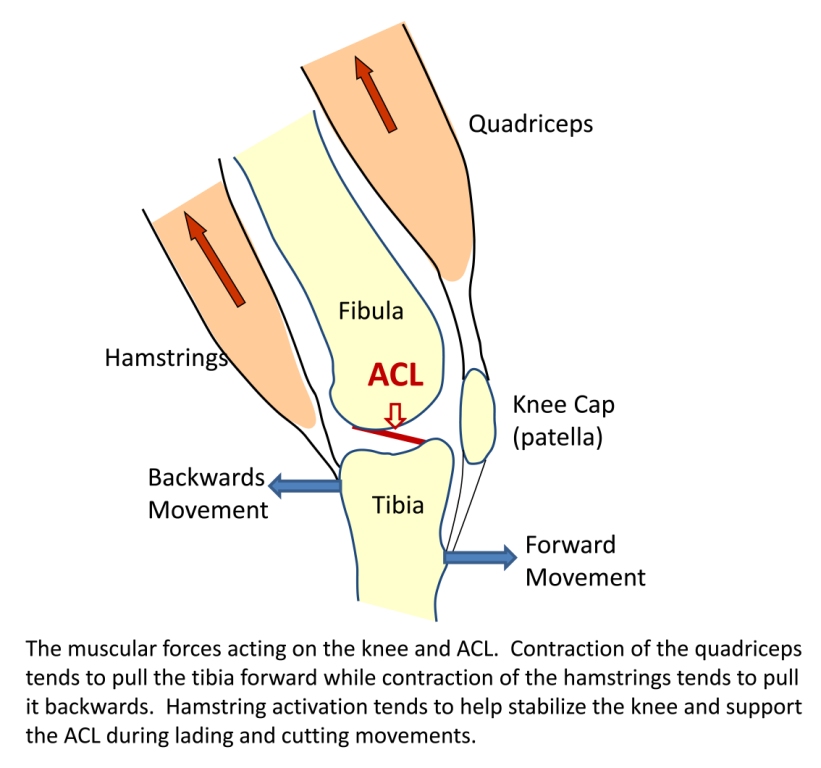

When you injure your knee – specifically the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) — the likely cause is relatively weaker hamstrings.

Imagine carrying a tall stack of books. Let’s say you’re walking briskly, and then suddenly stop. What happens? The top books will probably slide forward, maybe even slide right off the pile, because you can only hang on to the lower books.

Now imagine that the bottom books are your shin (tibia) and the top books are your femur.

Your hamstrings help your ACL stabilize the knee by stopping the books sliding — they halt the forward movement of the tibia on the femur (aka anterior translation of the tibia on the femur). Hamstrings grab the upper-level books and pull them so the stack stays intact.

If your quads are too strong compared to your hamstrings, a sudden change in direction or awkward landing can cause the knee to slide forward and cause an ACL tear.

Okay, I’ve convinced you that your physio was right and that you have a muscle imbalance and you should fix it. But how?

Research question

Well, you’re in luck, because this week review looks at different ways of measuring the hamstring:quad ratio and how a strength program can help.

Holcomb WR, Rubley MD, Lee HJ, Guadagnoli MA. Effect of hamstring-emphasized resistance training on hamstring:quadriceps strength ratios. J Strength Cond Res. 2007 Feb;21(1):41-7

Methods

Participants

Since female athletes are the most susceptible to ACL sprains, the researchers decided to have female soccer players as their test subjects.

There were twelve female National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) division I soccer players (about 20 years old). Participants had no previous significant knee injuries and no history of ACL surgery or rehabilitation.

The participants were not doing any formal strength training for 8 months before the study. Oh, another thing: For some reason, soccer players do very little weight training. When I played varsity soccer in Alberta we did no formal weight training. Just to compare, my junior high basketball team had a formal weight training program and made sure the athletes had access to a workout facility through the summer.

Why the aversion to strength training? I haven’t figured out a good reason – must be tradition.

Anyway, back to the study. Testing included hamstring and quadriceps strength – no big shocker – but, they did include some interesting measures.

After looking at concentric quadriceps and concentric hamstring strength ratios (conventional H:Q ratios) they looked at concentric quadriceps ratio to eccentric hamstring ratios (functional H:Q ratios).

Dr. Faulkner, proposed that eccentric and concentric be thrown out of muscle physiology and replaced with lengthening and shortening. So when the muscle is getting longer (lengthening) then you would call it a lengthening contraction – NOT eccentric – simple. And when the muscle is getting shorter you would call it a shortening contraction instead of concentric.

Lengthening hamstring strength versus shortening quadriceps strength

By looking at the strength of the hamstrings while they are lengthening and the strength of the quadriceps while they are shortening, you have a better idea of what happens during running and jumping.

As I’ve mentioned, when you run, your quadriceps shorten as your knee straightens. At the same time, your hamstring must be lengthening. If not, then you have trouble.

Peak strength measurements

After a warm up the participants were tested on an isokinetic dynamometer – an instrument that measures the peak torque (N · m) at a specific speed. In this study the speed of contractions tested were 60 degrees/second, 180 degrees/second and 240 degrees/second.

If you’ve ever used a Cybex or other equipment using hydraulic pistons, then you’ve done isokinetic exercises similar to the tests used in this study.

The strength program

After testing, the participants trained for 4 days a week for 6 weeks.

Days 1 & 3 were upper body, speed and agility training days. Days 2 & 4 were endurance conditioning and lower-body days.

The lower body days were designed to emphasize hamstring strength. Two of six possible exercises were included in the hamstring-focused workouts.

The breakdown of sets, reps and rests were unreported – and they didn’t even mention what other leg workouts they were doing. So much for repeatability.

What were the six exercises? Exercises you should be doing, such as:

- Single leg curls

- Straight leg deadlifts

- Good mornings

- Trunk hyper extensions

- Sled walking

- Exercise ball curls

Results

Functional hamstring:quadriceps ratios

Before the exercise program, the average ratio was 0.96 — meaning the hamstrings were slightly weaker lengthening than the quadriceps were at shortening. Even though it wasn’t a big difference, the weakness in the lengthening of hamstring can increase the risk of hamstring pulls/tears and ACL injury.

After the exercise program there was a (statistically) significant difference in the ratio, to 1.08 – a 12% increase.

Other differences that weren’t because of the strength programs were dominant versus non-dominant legs.

The dominant legs had a functional ratio average of 0.94 and the non-dominant leg had a functional ratio average of 1.10. I’m not surprised by this, because as soccer players the quadriceps of their dominant leg are used to kick the ball and over the years they become stronger than the non-dominant quadriceps – but the hamstring strength stays the same.

Depending on the speed of contraction the ratios changed. At relatively slow contraction speeds – 60 degrees/second – the average ratio was 0.74, compared to 1.10 at 180 degree/second and 1.23 at 240 degrees/second. So the slower the contraction, the bigger the difference in ratio and maybe an increased chance of injury.

Conventional hamstring:quadriceps ratios

Comparing conventional H:Q ratios (both muscles’ max shortening strength) before and after the strength program showed no difference. None. Zippo. Zilch. The averages were 0.82 before and 0.88 after the program. While there was an improvement, it wasn’t enough to be considered different. Perhaps a longer strength training program would have caused differences.

Same as with the functional H:Q ratios there were differences in dominant and non-dominant legs (0.78 versus 0.92) and speed of contractions (0.79 at 60 degrees/second, 0.89 at 180 degrees/second and 0.92 at 240 degrees/second).

Conclusion

Many of us have heard your hamstrings need to be at least 60% (0.60 H:Q ratio) as strong as your quadriceps (1) to prevent injury. But that is concentric or shortening strength.

It seems this functional hamstring to quad ratio makes more sense with the lengthening (eccentric) strength of the hamstrings being compared to the shortening (concentric) strength of the quads. In the functional Hecc:Qcon ratio you want less than 1.0 at speeds more than 120 degrees/second.

This may sound obvious, but I’ll spell it out – you improve your H:Q ratio by doing more hamstring strength training.

Female athletes, since they are more likely to have ACL injuries, should do their best to increase hamstring strength and better their H:Q ratios.

Oh you may be wondering why the functional H:Q ratio changes with the speed of the contraction. Well it’s because increased speed means greater force in lengthening contractions (eccentric), but less force in shortening (concentric) contractions (2).

Bottom line

Focusing on hamstring strength improves your hamstring to quadriceps ratio – more for the functional H:Q ratio, but still there is improvement in the conventional H:Q ratio.

For the vast majority of us, more hamstring work is nothing but beneficial. I have yet to hear about someone tearing a quad because their hamstrings were too strong. If anybody has, please e-mail me.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Learn more

Want to get in the best shape of your life, and stay that way for good? Check out the following 5-day body transformation courses.

The best part? They're totally free.

To check out the free courses, just click one of the links below.

Share