Food labels may help us make better decisions at the grocery store. This article looks at why we label food, what’s on those labels, and where label information comes from.

Why label food?

In theory, food labels help us make informed – and, ideally, healthier – decisions. Having food and nutrition information available to us in a quick-reference format may help us choose the best foods for our needs.

Food labels also ensure that manufacturers are accountable and transparent; in other words, that what you see on the label is what you truly get.

In theory, that is. But does that hold true in practice?

Short answer: Yes and no.

Label types

There are two general types of labels:

- Legally required labels: These are governed by laws and regulations around packaging and the provision of nutritional information. Usually these are on the back of the package and give information like ingredients and nutritional value.

- Industry-provided labels: These are placed at the manufacturers’ discretion. Usually these are on the front of the package.

We’ll look more at back-of-package versus front-of-package labeling more closely in Part 2.

Regional variation

Several countries, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, Korea, and New Zealand, have mandatory food labeling. Elsewhere, food labeling is up to the manufacturer, although the EU has been discussing food labeling for several years.

Table: Food labeling laws in selected regions

| Region | Food labeling | Governed by | Overseen by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Mandatory | Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code | Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) |

| Canada | Mandatory | Canada’s Food and Drugs Act and Regulations | Health Canada |

| EU | Mandatory | Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 | European Commission |

| Japan | Mandatory | Quality Labeling Standard for Processed Foods | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries |

| New Zealand | Mandatory | Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code | Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) |

| United States | Mandatory | Nutrition Labeling and Education Act | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) |

Food manufacturers have often asked to be in charge of their own labeling, arguing that labeling rules and regulations involve a lot of bureaucracy.

However, voluntary industry-provided labeling has other challenges, such as:

- Transparency: Who gets to decide what’s on the label? How do they decide? Can we as consumers and citizens see and be part of this decision process?

- Meaningful criteria: What is on the label, and why?

- Accountability and objective evaluation: Who do food companies report to? Who decides what’s on the label?

- Oversight: Who ensures that companies are being truthful and accurate? And if they aren’t, who enforces the rules?

History suggests that relying only on industry-provided labeling may not always be in the public’s best interests.

For instance, in 1954, top tobacco executives put out an ad claiming, “We accept an interest in people’s health as a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in our business.”

The last 50 years haven’t exactly borne out that promise.

As one researcher points out:

“Allowing an industry to self-regulate without input from government, consumers, or public health advocates can have serious consequences. Self-regulation can become a public health failure when:

(1) leading companies fail to take part,

(2) weak standards permit harmful practices,

(3) standards do not apply globally,

(4) credibility is undermined by an absence of transparency and objective scientific input, and

(5) a lack of benchmarks and objective evaluation leads to ambiguity in interpreting both compliance and impact.” (Sharma et al 2010: 245).

In other words, don’t leave the foxes in charge of the henhouse.

Thus, governmentally legislated and regulated package labels have been an important part of consumer information and preserving public health and safety in several countries worldwide.

Having clear rules and laws ensures that product labels are standardized, accurate, honest and based on scientific evidence.

What counts as “label-worthy”?

Food labels typically give information such as:

- Ingredients (including specific additives, such as coloring, emulsifiers, and preservatives)

- Nutrition information (e.g. calories, grams of fat)

- Suggested serving size

- “Best before” date

- Where the food comes from

- How to use and store the product

Ingredients

Generally, ingredients appear in order of proportion. In other words, if bread is mostly wheat flour, then wheat flour will be the first ingredient.

In Australia, manufacturers must also specify what percentage of a food is made up by a given ingredient – for instance, if a yogurt contains 6% fruit, the package will say “strawberries (6%)”.

Label display

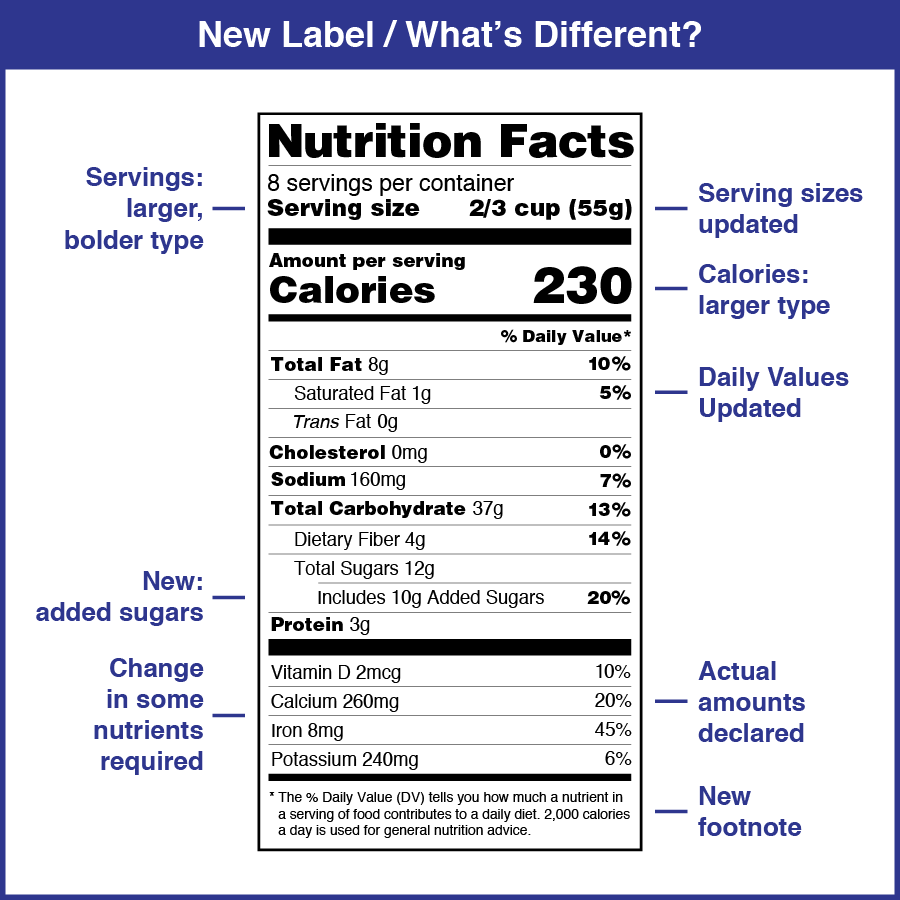

Other rules control how the information is actually presented. Below is an example of the label specifications for a U.S. food label.

Above: example of the rules governing food label display.

Genetically modified (GM)

Rules vary from place to place about whether food can/should be labeled as organic and/or genetically modified (GM).

Some regions, such as Australia, China, the Czech Republic, and South Korea, will label and/or strictly regulate GM ingredients. The EU goes one step further and also requires labeling of meat produced with GM feed. (In fact, European countries have rejected foods from U.S. suppliers that don’t meet EU GMO standards. Which makes you wonder what we’re getting here in North America.)

Generally, in countries that do label GM foods, anything with more than about 0.5-3% GM ingredients has to be labelled as such.

How do food companies get data for their products?

Unless you have a food analysis lab in your garage, and/or make everything from scratch on your farm where you grow all the components, you have to rely on the companies making the food to tell us what’s in their food.

Ever wondered where food manufacturers get their label information from? We have too.

For nutrition information labels, companies might test a food “in-house” at a food lab or send it away for analysis.

Sometimes the new food itself isn’t even tested. Rather, the nutrients/calories are estimated based on existing information in nutrition software programs.

Existing food products might be re-analyzed on occasion, but this depends on company protocol.

Small food companies aren’t required to have nutritional info on labels until they gross over $100,000/year. This can be an expensive transition process for new businesses.

Ryan contacted several companies to ask how they got their label data. Here’s what he found.

| Company | What they make | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| ConAgra | Wide variety of processed foods and brands, e.g. Chef Boyardee canned pasta, spreads such as Parkay and Blue Bonnet, snack foods, packaged breakfast foods, cooking oils such as Pam | I called ConAgra and spoke with a rep. They have an in-house food testing lab and test all new products. They re-test older products when ingredients change. |

| Kraft | Wide variety of processed foods and brands, e.g. dips & spreads, cookies, crackers, drink mixes, pastas and pizzas, snack foods, etc. | I called Kraft and spoke with a rep. They don’t have any information on how the calories and nutrients are established for their food products. Hmmm. |

| Kellogg’s | Wide variety of foods and brands, particularly packaged cereals and grain products such as granola bars, frozen waffles, and Pop-Tarts | I called Kellogg’s and spoke with a rep. They have an in-house food testing lab. If any changes occur to existing food products, they’ll retest. |

| Hain Celestial | Many “health food” brands such as Rice Dream, Almond Dream, Maranatha nut butters, Yves Veggie Cuisine, and Earth’s Best | I called and emailed with no response. |

| General Mills | Wide variety of processed foods and brands, e.g. Pillsbury, Green Giant frozen vegetables, breakfast cereals, Old El Paso Mexican foods, Nature Valley, Betty Crocker, Haagen-Dasz, yogurt, various snack foods | The only info I received from General Mills included the following: General Mills labels the nutrient values of food products in accordance with the Code of Federal Regulations published by the FDA. |

| ESHA | ESHA sells computer software to companies. They have a huge database of calorie/nutrient information. | I spoke with a rep, who explained that ESHA gets this information directly from the food companies. |

The role of the USDA

Most everyone in the world of nutrition nerdery is familiar with the USDA nutrient database. It’s the Holy Grail for calories and nutrients. Various organizations (such as NutritionData.com) get their data from it.

Ryan called Joanne Holden, MS, a research leader at the USDA and asked her a few questions about it. Here are some key facts.

The USDA nutrient database contains about 7600 foods — a lot, but not everything. They release a partial update each year updating foods that are changed (e.g., new reduced sodium soups, etc.).

Since the USDA doesn’t have a budget for food item analysis, they are limited to testing 60-70 foods per year. If a food company makes big changes (e.g., Kraft lowers sodium in their products), the USDA is aware and tries to stay current.

The USDA collaborates with others. They actually get beef and pork nutrition data from the beef and pork industry. It’s a joint project. So not every food in the USDA database is analyzed by the USDA.

The USDA commissions people around the U.S. to collect samples of the food they are testing from 12 major grocers (no mom and pop markets). So, if frozen cheese pizza is being analyzed this year, the top 3-4 frozen pizza brands would be identified (based on market share). Then, 12 samples (from 12 major supermarkets around the country) of these 3-4 frozen pizza brands would be analyzed.

The USDA often generates a “generic” listing for popular foods like “frozen cheese pizza” since it’s expensive to maintain brand name information in the database. Translation: if you get a unique/small brand of frozen cheese pizza, the nutrition data might not align with what’s found in the USDA database.

The calorie and nutrient data is generated by commercial labs with whom the USDA collaborates. Each lab has strengths/weaknesses. Some have more comprehensive testing for vitamins, some for minerals, some for calories, and so forth.

To measure calories, the USDA measures the macronutrients of food. This adds up to the total energy/calories. They use specific Atwater factors, a system for calculating the available energy of foods. These factors were determined more than 100 years ago. Fiber tends to be the most tricky to determine because the methods for analyzing fibers aren’t consistent. Different methods get different results.

We’ll return to the issue of how accurate and relevant this data is in Part 4.

In the meantime, you can check out this article for more:

Energy Value of Foods: Basis and Derivation

Summary and action tips

- Food labels can be important sources of information.

- Food labels can help us make smart, healthy decisions.

- However, food labels may not accurately reflect what’s in the package.

- Be a critical consumer and don’t always assume what’s on the label is useful or accurate.

- Processed/pre-packaged foods will have the most variation. Company data may not be accurate.

- If you’re concerned about what’s in your food, stick to whole foods and use the USDA nutrient database (or a comparable, relatively unbiased scientific database that does its own analysis) to figure out what’s in those foods.

- Recognize that even “unbiased” numbers may not be 100% precise or useful. Don’t get too hung up on the numbers.

To continue learning about food labels, check out part 2 of this article series where we examine food label claims.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share