Can body type—whether ectomorph, mesomorph, or endomorph—determine what sports suit you best, as well as what you should be eating to fuel your activities? The answer isn’t black and white. Nutrition science is notoriously confusing, which invariably leads to debates about what works—and what doesn’t.

Eating for your somatotype, or body type—“soma” is Greek for “body”—is one of the most heavily debated nutrition topics in our community.

At Precision Nutrition, we’ve found that people tend to fall into one of two categories on this subject.

- They place way too much importance on body typing.

- They dismiss body-type as complete pseudoscience.

On both sides of the debate, we’ve also found that people buy into myths, such as:

“Everyone should eat according to their body type.”

Or…

“No legitimate scientist would ever use body typing.”

Like so many hotly-contested topics, the truth lies between the two extremes.

Here’s the truth: For most people, body type eating isn’t necessary or important.

For them it’s just not the most effective tool for their needs and goals.

So why bother discussing it?

Because this is also true: Based on our work with more than 100,000 clients, we’ve discovered that body type eating can benefit some people in a couple of highly specific situations. This is especially true when foundational nutritional strategies aren’t enough to get these individuals all the way to the finish line.

In this article, we’ll explain:

- the origins of body typing

- what science reveals about body typing

- how to know if a body type diet is right for you (or your clients)

- how to try body type eating for yourself (if desired or appropriate)

++++

You’ve probably heard about three body types. What you may not know: countless types exist.

In the 1940s, psychologist Dr. William Sheldon came up with the idea of somatotypes. (In case you missed it earlier in the article, somatotype is just another word for body type).

Originally, Sheldon thought body size and shape helped to determine personality traits such as assertiveness, aggressiveness, shyness, and sensitivity.

He was wrong.

But his three main body type classifications (endomorph, mesomorph, and ectomorph) live on, though they’ve evolved—for the better.1-5

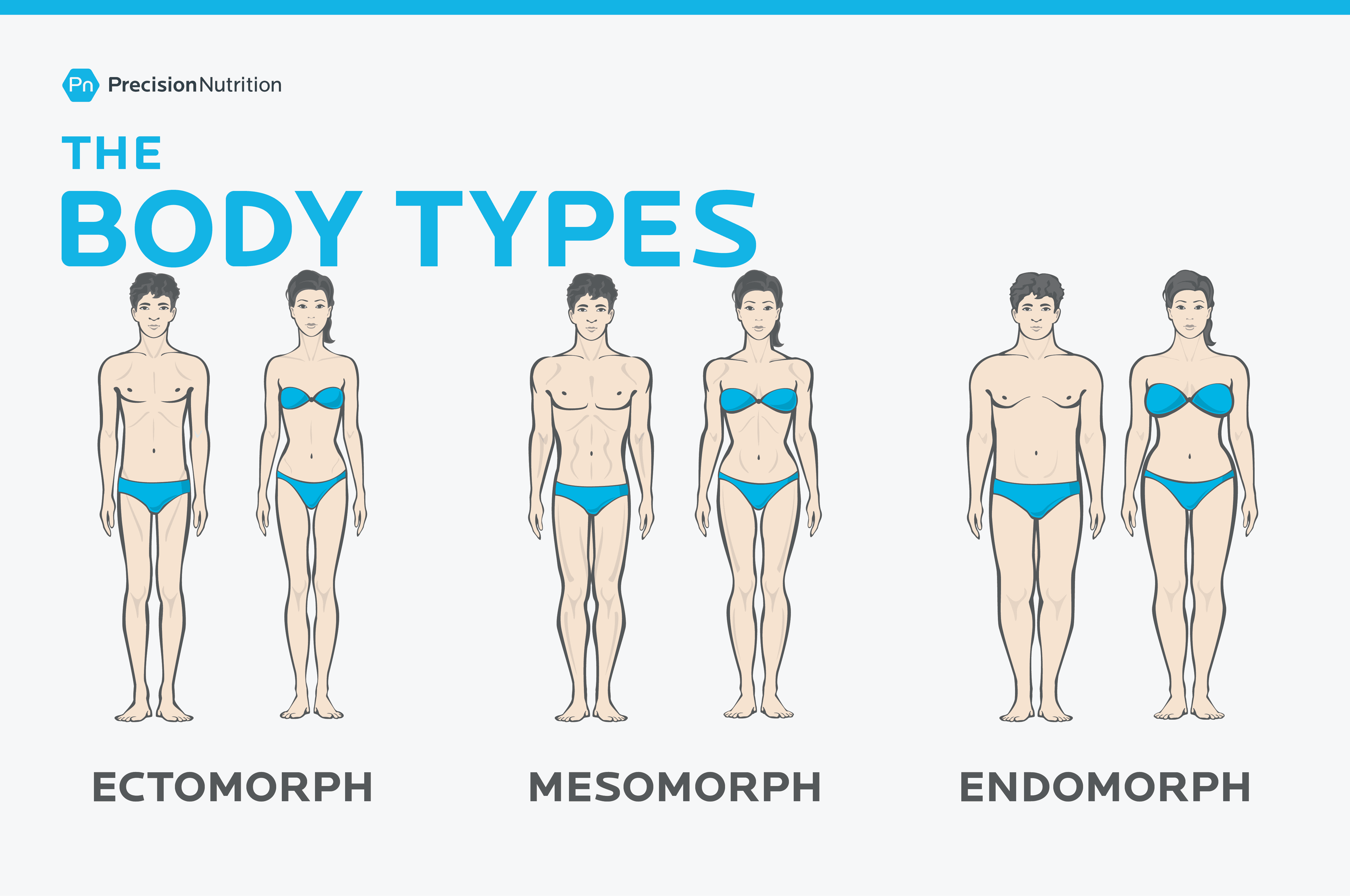

According to Sheldon’s definitions:

Ectomorphs were thin, narrow, delicate, fragile, linear, and poorly muscled.

Endomorphs were soft, round, pudgy, and overweight.

Mesomorphs were broad-shouldered, narrow in the waist and hips, muscular, compact, and athletic.

Sheldon determined those types based only on height and weight, and front, side, and back photos (known as photoscopy). But other scientists soon rightly criticized this method as unreliable and subjective—because it was.6

Eventually, Barbara Honeyman Heath Roll and Lindsay Carter developed the currently used method for evaluating body type. It assesses and scores body type based on 10 distinct measurements.6-8. According to their method:

Endomorphy is relative fatness or leanness as determined by the sum of three skinfolds taken at the triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac. The higher the sum of these folds, the higher the endomorphy score.

Mesomorphy is muscle mass relative to height. It’s determined by the width of the elbow and knee, flexed arm circumference corrected with triceps skinfold, and calf circumference corrected with medial calf skinfold.

Ectomorphy is the lack of body mass (body fat and muscle mass) relative to height and is determined using someone’s height and weight.

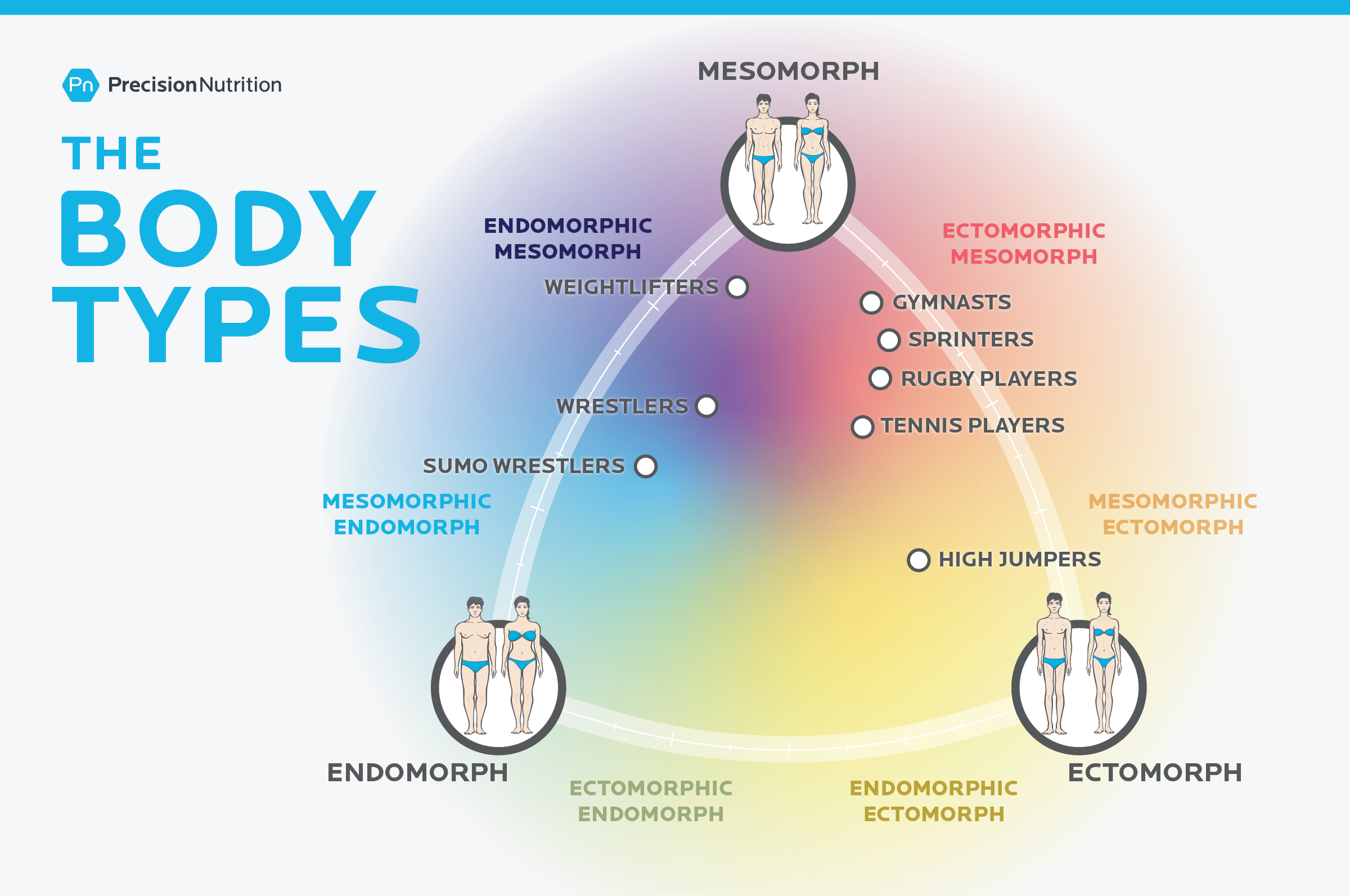

Once calculated, these values are plotted on a tri-axial graph to determine a person’s somatotype.9,6

Compared to Sheldon’s approach, the Heath-Carter method more closely resembles a body composition measurement, providing a more accurate description of a person’s ratio of fat to muscle to bone.10

It also allows for a wider variety of body types, such as mesomorphic ectomorphs or endomorphic ectomorphs (what some people refer to as skinny-fat). As you can see on the graph below, the typical gymnast might be more mesomorphic and the typical sumo wrestler more endomorphic, but neither falls 100 percent into one category or the other.

So despite what many think, the Heath-Carter method is actually highly individualized. Still, even though nearly everyone is a mix of body types, most folks can find their general tendencies in one of the three groups.

And no matter which group someone resembles, they’re not stuck. They can change their body type. For instance, bodybuilders mistaken for “natural” mesomorphs may actually be endomorphs who’ve trained and dieted hard. Or they could also be ectomorphs who’ve spent years guzzling protein shakes and lifting weights.

Your body type is not a life sentence.

Somatotype describes body components like fat mass, lean mass (muscle), and the ratio between the two—not unlike measuring someone’s body composition. That’s why, over the years, somatotype has become an assessment tool for medical professionals and researchers, similar to body mass index (BMI). While neither is a perfect system, both BMI and somatotype are simpler and more affordable than other measurement tools, which makes them accessible to more people.

That’s why, just as BMI can change over time, so can body type.

It’s just a tool used to describe someone’s body. That’s it. Like BMI, body typing gives you an idea of whether someone who is 200 pounds and 5’10” is obese, very muscular, or somewhere in between, which can be valuable in a clinical or coaching setting. It helps you to know, for example, how someone’s body is truly affecting their health.

Over the years, researchers have tested whether somatotypes correlate to other measures or traits. So for example, researchers have looked into questions like:

- Is there an association between somatotypes and personality? Sorry Dr. Sheldon, but no. As it turns out, people with ectomorphic bodies are not the only ones who feel self-conscious. Similarly people with mesomorphic body types don’t necessarily take more risks than people with other body types. In other words, we all have a body and we all have a personality, but our bodies do not necessarily influence our personalities and vice versa.

- Is there an association between somatotypes and genetics? Yes. Based on studies that looked at identical twins, we know that mesomorphy and ectomorphy are both highly linked to genetics (both about 70 percent) while endomorphy is much lower (30 percent). For a comparison, height has a heritability of about 80 percent.11,12

- Is there an association between somatotypes and athletic performance? Yes. Research has linked somatotypes with the fast-twitch muscle variation of ACTN3, the only gene associated with power athletes. Mesomorphs are more likely to have this “fast” gene than other body types, which may explain why sprinters tend to fall into the mesomorphic body type.13-16 Elite marathon runners tend to be ectomorphs while elite sumo wrestlers are usually more endomorphic.17,18

- Is there an association between somatotypes and cardiovascular disease? Yes. Because of this, you may be more or less likely to develop high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, and other heart disease risk factors. Here’s why. Fat and muscle both serve as endocrine organs that produce hormones and proteins. Fat makes substances called adipokines, and skeletal muscle makes myokines.19-22 A recent study suggests that these substances regulate high blood pressure (hypertension) reciprocally. Overall, myokines (from muscle tissue) seem to decrease hypertension while adipokines (from fat tissue) increase it.23

Should you eat for your body type?

Mostly no.

Before we explain why, we first want to get really clear about our own stance on this—and how it has evolved. In the past, we’ve used body typing as a tool to guide advanced clients, and coaches working with advanced clients (i.e., clients who had already mastered nutrition fundamentals and had higher-level performance or aesthetic goals). In the 3rd Edition of our Level 1 Certification textbook (which was written and released in 2016), we wrote:

“Importantly, these are just general conceptual categories—principles that can potentially help us target our nutritional strategies. Body types are not ‘carved in stone.’ They’re not the basis for ‘nutritional rules,’ nor are they any specific system…

Body types are a proxy for thinking about possible differences in metabolism, activity types, and nutritional needs. As a coach, you can create some working hypotheses using body types, which you can then test.”

But, in our brand-new 4th edition textbook, we completely removed references to body typing. Why? It’s not because we don’t think body typing has value. It does—for a few people. But, for the vast majority of people, body typing creates more questions than answers.

For the average person who just wants to look and feel better, body typing serves as a giant distraction. It also makes nutrition unnecessarily complicated. For these people, much simpler and more approachable strategies work beautifully, and frankly, better. That’s why we now recommend body typing only as a third step in a multistep progression.

So who does benefit from body typing? Two types of people generally fall into this camp: High-performance athletes and people who couldn’t achieve their goals through foundational strategies alone.

In those very rare cases, altering macronutrient breakdowns based on body type (or more specifically, fat to muscle ratio) can be an effective strategy, but only after someone has mastered the fundamentals.

Which brings us to… the fundamentals.

(Want more deep insights and helpful takeaways on the hottest health and nutrition topics? Sign up for our FREE weekly newsletter, The Smartest Coach in the Room.)

Step 1: Master foundational nutrition habits.

The following simple and accessible strategies can help most people reach their goals. Try these for yourself or your clients first.

Consume mostly whole foods. Whole foods include fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, beans and legumes, whole fresh cuts of meat and poultry, seafood, and nuts and seeds. Choose whole foods over processed ones whenever possible, aiming to make small improvements to each meal rather than doing a giant overhaul all at once. For example, can you add more veggies to your fast food sandwich? How about eating a side salad with dinner? Before you reach for a crunchy, processed snack food, consider whether crunchy fruit (apple slices, for example), veggies (cucumber slices), or nuts (roasted almonds) could hit the spot.

Eat slowly. This practice will help you become more aware of what you eat, how much you eat, and why. You’ll also learn to eat less—automatically—because you’ll tune into your natural fullness cues. To do so: slow down as much as you can. Before you dig in, notice what you have chosen. Take a bite. Chew slowly. Take in the scent, texture, taste, and temperature. Put your utensils down or take a sip of water. Then have another bite as you attempt to slow down and savor the meal. And don’t worry if you find it challenging to slow down. Just like all new habits, this takes practice. (For more details about eating slowly, check out this 30-day challenge.)

Eat until you’re satisfied—but not stuffed. If you’re trying to lose weight, this strategy can help you to eat less without feeling deprived. Your goal: to stop eating after hunger dissipates, but before you’re completely full. On a 1 to 10 fullness scale, you’re aiming for an 8—or about 80 percent full. And don’t worry. You don’t have to get it right away. For your first meal, you might simply pay attention to how your level of hunger changes as you eat and progress from there. Whenever you eat until you’re uncomfortably full, forgive yourself and just keep trying. Over time, you’ll get the hang of it. And eventually, with enough practice, this will become more automatic.

(Note: if you want to maintain your weight, aim for about 90-100 percent full. If you are trying to put on mass, eat beyond fullness, until you are slightly uncomfortable—roughly 110-120 percent full.)

Emphasize protein and vegetables. Emphasizing these two categories at meals will help you lose fat, build muscle and strength, feel full, dial down hunger, and improve your health. For most people, this means aiming for 1-2 palm-sized portions of lean protein, and 1-2 fist-sized portions of vegetables at most meals. (Hate veggies? This article can teach you how to love them.)

Those four practices take most people from point A to point B. If you or your client have been following all four practices 80 to 90 percent of the time (which is the sweet spot for progress) and are still not making desired progress, it’s time for step 2.

Step 2: Track your food intake.

If the four practices listed in step 1 are not enough, you or your client may need to track your food intake. For example, you may need to consume fewer portions (for weight loss) or consume more portions (to gain weight). In either case, you’ll need an eating system to help you stay on track.

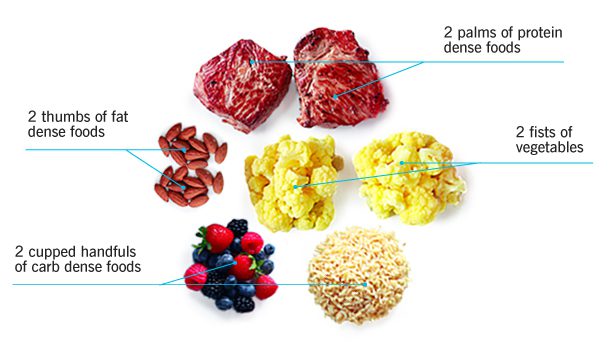

Many eating systems exist, from calorie counting to macro counting and more. (Read about the pros and cons of each). At Precision Nutrition, we recommend hand portions for most because they quickly and easily help people to determine the right portions for them. Sure, hand portions are not as precise as weighing and measuring food, but this system is close enough to help most people see results without a lot of fuss (in our experience it’s about 95-100% as accurate).

To get started, plug your or your client’s age, weight, and other data into our free Precision Nutrition Calculator. It will generate customized hand portions for each meal as well as provide a personalized comprehensive report and eating plan.

Step 3: Modify your macros based on your goals and/or body type.

This is where your body type may come into play—sort of.

But we first want to reiterate an important point: Most people don’t need to eat specific macros for their body type, and that’s okay.

It really is.

So only move onto step 3 once you or your client have been consistently following fundamental nutritional practices for months—if not years—and still need to make further progress.

We’ve found that two types of people tend to need step three to get themselves over the finish line. These clients include:

- People whose body type interferes with their goals. It really is harder for an endomorph to lose weight, for example, than an ectomorph. Conversely, it’s also more difficult for an ectomorph to put on muscle than it is for an endomorph. Usually consistently implementing step 2 (described above) is sufficient. But in the rare case it’s not, step 3 can help.

- High-level performance athletes such as powerlifters, bodybuilders, and marathon runners. For these people, a customized macro plan—with personalized percentages of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins—can make the difference between performing “meh” and reaching a personal best.

If you already know your body type, great. If you don’t, no biggie. You read that right. Just don’t worry about it. There’s no need to find a pair of calipers and a tape measure. All you need to know is this: your goal. That’s because the most common goals align with eating strategies created for specific body types. Find your goal below, along with the corresponding body type and eating strategy.

Goal: Lose Fat

Typical body type: Endomorphic

Though this eating plan is based on the endomorphic body type, it works for anyone with a fat loss goal, including mesomorphic athletes who just want to shed some fat in order to get completely shredded.

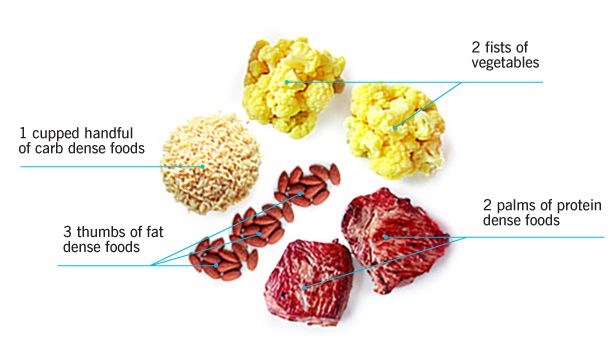

To reach this goal, use these approximate macros:

- 35 percent protein

- 25 percent carbohydrates

- 40 percent fat

Don’t get hung up on the math. Just think: more fats and protein, fewer carbs. If you need to eat during exercise (because you’re really pushing yourself beyond 60 minutes of sustained high effort), gravitate toward protein powder or essential amino acids (EAAs), reserving carbohydrate sports foods (such as gels and sports drinks) only for the most strenuous sessions lasting (Think: an all day soccer tournament, a marathon, a powerlifting competition, or a long, grueling ride in intense heat). For carbohydrate intake at meals, focus on whole, minimally-processed, carbohydrate-dense foods—and limit your consumption of starches and fruits, aiming for about a 4:1 veggie-to-fruit ratio (four vegetables for every 1 fruit.)

Using our hand-portion system, a general framework for this looks something like:

- 1-2 palms of protein dense foods at each meal

- 1-2 fists of vegetables at each meal

- 1-2 cupped handfuls of carb dense foods at each meal

- 3-4 thumbs of fat dense foods at each meal

Goal: Push Endurance or Gain Muscle

Typical body type: Ectomorphic

If you’re doing high-volume exercise such as long-distance running or cycling, this is the plan for you. You’ll consume macros designed for the slender ectomorphic body type (lack of muscle, lack of fat), whether you are a natural ectomorph or not. Even if your body type is more mesomorphic, you’re more likely to reach this goal if you follow an ectomorphic-style diet that includes proportionally more carbohydrates, less fat, and moderate protein.

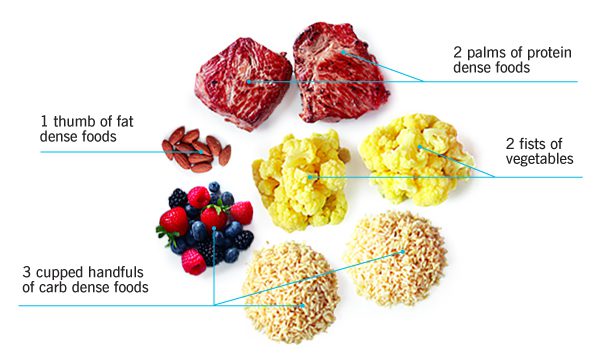

This plan is also ideal if you are or think of yourself as a “hard gainer,” as you need ectomorphic-style eating to consume enough calories to overcome your body’s resistance to putting on weight / muscle. Remember: true ectomorphs tend to lack both fat and muscle. To pack on muscle, it helps to consume more carbohydrates, less fat, and moderate protein. In other words, you’re looking at the same macro strategy as an endurance athlete. Specifically, that looks something like:

- 25 percent protein

- 55 percent carbohydrates

- 20 percent fat

Don’t drive yourself crazy with macro math. Just think “more carbs and fewer fats”. Whenever possible, try to consume carbohydrates (such as sports drinks and high sugar foods) during or after your workouts. For carbohydrate intake at your meals, eat whole, minimally-processed, carbohydrate-dense foods liberally, aiming for about a 2:1 veggie-to-fruit ratio. (In other words, for every 2 servings of veggies you consume, have a serving of fruit.)

Using our hand-portion system, a general framework for this looks something like:

- 1-2 palms of protein dense foods at each meal

- 1-2 fists of vegetables at each meal

- 3-4 cupped handfuls of carb dense foods at each meal

- 1-2 thumbs of fat dense foods at each meal

Goal: Boost power

Typical body type: Mesomorphic

Need more explosive power to knock off your next WOD or boost your hockey, soccer, sprinting, or basketball game? Then you’ll want to eat like a mesomorph (low fat, high muscle) so you can add muscle while staying lean.

Follow a mixed diet, consisting of balanced carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Specifically, we’re talking about:

- 30 percent protein

- 40 percent carbohydrates

- 30 percent fat

Consume fast-digesting carbohydrate-dense foods and/or drinks during intense exercise sessions, as needed. During meals, your carbohydrate intake should focus on whole, minimally-processed, carbohydrate-dense foods, in moderation, aiming for about a 3:1 veggie-to-fruit ratio. (In other words, three veggies for every one fruit serving).

Using our hand-portion system, a general framework for this looks something like:

- 1-2 palms of protein dense foods at each meal

- 1-2 fists of vegetables at each meal

- 2-3 cupped handfuls of carb dense foods at each meal

- 2-3 thumbs of fat dense foods at each meal

Step 4: Adjust as needed

The first few steps will help most people reach their goals. But there are always outliers.

If you or your client still have a way to go—despite consistently sticking with steps 1 to 3—that doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong.

It just means you need a personalized nutrition approach.

And the only way to find the best nutrition approach for you or your client’s unique needs is to do this: experiment.

Try a new eating strategy. Observe how it works (or doesn’t work). And either maintain or adjust from there, depending on the outcome.

And consider signing up for coaching—so you can work closely with a professional who can help you to see your blind spots, suggest new alternatives, and stay motivated.

Here’s a quick recap.

If you or your client are brand new to the world of healthy eating: Don’t worry too much about body types and macros. Start with the fundamental nutrition practices: choose whole foods, emphasize vegetables and lean proteins, eat slowly, and end meals when you’re 80 percent full or just satisfied.

If you’ve mastered the fundamentals, but want to lose more weight or gain more muscle: Reduce/increase your calorie and macronutrient consumption. Our Nutrition Calculator and hand-portion system can help.

If you’re a performance athlete: It may be time to try body type eating—with body type and goal-specific macros. Figure out your goal (lose fat, gain muscle, boost endurance, add power) and/or your body type (endomorphic, mesomorphic, ectomorphic) to find the best macro plan for you. (See step 3 for details.)

If you’ve tried everything and none of it is working: Experiment. If you’ve used a strategy in the past and it didn’t work, then don’t do it again. Try new strategies, track your progress, and adjust from there.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a health and fitness pro…

When your clients are stressed and exhausted, everything else becomes a struggle: going to the gym, choosing healthy foods, and managing cravings.

But with the right tools, you can help your clients overcome obstacles like chronic stress and poor sleep—leading them toward the lasting health transformations they’ve always wanted.

PN’s Level 1 Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery (SSR) Coaching Certification will give you these tools. And it’ll give you confidence and credibility as a specialized coach who can solve the biggest problems blocking any clients’ progress. (You can join the SSR Early Access List for our biggest discount + exclusive perks.)

Share