“I want to know I’m doing absolutely everything I can to preserve my health for as long as possible.”

We hear this kind of thing a lot.

People tell us they not only want to stay in good shape as they age, they also want to outlive their peers and age expectancies.

Imagine you could maximize your healthspan and lifespan, fend off disease, and generally remain fit, lean, and youthful into your 90’s, 100’s, and then some.

Sounds pretty compelling, doesn’t it?

There’s just one problem: Common longevity advice seems to involve an extraordinary amount of effort. And time. And money. And complexity.

Is all the effort necessary? Is it worth it?

And, will it even work?

In this article, we’ll explore:

- The biggest myths—and realities—about optimizing your health

- The real costs and tradeoffs of “optimizing” your health

- What’s actually required to improve your healthspan and lifespan

- Why enjoying your life isn’t separate from good health; it’s part of it

And, we’ll help you weigh the pros and cons so you can make informed decisions about your health, your body, and your life.

The myths—and realities—of “optimizing” your health

Health and longevity advice is everywhere these days: podcasts, books, social media, that guy at the gym…

Plus, influential “figureheads” have given the movement outsized attention. Think: popular podcasters and health experts Dr. Peter Attia, Dr. Andrew Huberman, and Dr. Rhonda Patrick, and biohacker Bryan Johnson.

We understand the appeal of this kind of content. Who doesn’t want a longer, healthier life? (Not to mention the comforting sense of control that can come from designing and executing a “perfect” health plan.)

But for us at PN, where we’ve collectively coached hundreds of thousands of people with real human lives, we know that “optimal” is rarely realistic.

Not only that, optimal isn’t necessary.

Making modest, relatively consistent efforts towards health and well-being will likely give you better results than following an intense, highly “optimized” protocol.

If that sounds hard to believe, we get it. So let’s explore that bold statement, starting with the biggest myths surrounding longevity and health optimization.

Myth: The “basics” aren’t enough.

There’s an idea that getting and staying healthy must require a set of complex, “cutting edge” strategies—especially if your goal is to outlive the average American.

In reality, the “basics” work really, really well. (These are things like exercising regularly; eating a nutrient-rich diet; getting adequate sleep; managing stress; and staying socially connected. We’ll discuss these more later.)

Only, very few people do the basics consistently.

The real reason more people aren’t living as long, or as well, as they could be isn’t because they’re not taking ice baths or getting vitamin C infusions…

It’s because they’re not doing the (relatively) simple stuff, consistently.

If you’re really, truly doing a well-rounded set of health-promoting behaviors with 80-90 percent consistency, you’re probably already close to peak optimization.

Myth: More is better

If a handful of basic behaviors get results, then doing them perfectly and as much as possible will help you get, and stay, even healthier—right?

Not so fast. There’s a law of diminishing returns when it comes to health and fitness efforts.

Plus, in our experience, doing too many things or adding in too much complexity to your health and fitness regime can:

- Add risk factors that could actually make your health and fitness worse (such as chronic injuries or burnout due to overtraining, and/or nutrient deficiencies or disordered eating due to an over-preoccupation with “clean” or restrictive eating).

- Make it harder for you to sustain good habits. People who take on too much are more likely to burn out. Research shows people who try to accomplish multiple goals are less committed and less likely to succeed than those focused on a single goal.1

- Make your life less enjoyable, which in turn compromises health. Striving to maximize physical health can interfere with mental, emotional, and social well-being, which plays an essential role in healthspan and lifespan. (One study showed people with high levels of happiness and life satisfaction lived up to 10 years longer than people with low levels.2)

And what’s the point of living longer if you’re not living a full, well-rounded, enjoyable life? While some effort is definitely important, past a certain point, more isn’t necessarily better.

Myth: Cutting-edge strategies offer significant benefits.

Let’s say you could put all those advanced, complex strategies into action without sacrificing consistency or life enjoyment, or compromising your overall well-being.

They’d have to pay off, wouldn’t they?

Not necessarily.

Much of the research on longevity optimization (so far) is either in mice, is observational, is theoretical, or has been tested on very small numbers of people for very short periods of time.

In fact, many of the fringe methods and supplements touted by influencers or biohackers are not only unproven but even potentially unsafe.3 4 5 6

Point being: Put your efforts towards foundational health behaviors with proven track records (the kind we’ll cover in this article) before you invest in fringe efforts.

Myth: It’s all or nothing.

You might think, “Well, I’m not getting out of bed at 5 a.m. five times a week to go running for 60 to 90 minutes to optimize my VO₂ max, so I may as well just accept I’m not going to be a healthy person.”

Some folks feel overwhelmed by the idea of optimizing their health, so they figure they might as well do nothing.

However, our internal data shows that you can be far from “perfect” to get results.

In our year long PN Coaching program, even clients who practiced their (basic) habits less than half of the time got measurable results.

(Read more: Nearly 1 million data points show what it REALLY takes to lose fat, get healthy, and change your body)

Don’t let optimization culture convince you great health is beyond your capabilities.

Instead, we encourage you to…

- Consider your options. Review the facts, and get a clear understanding of which behaviors are most likely to give you the best bang for your buck.

- Get clear on the tradeoffs. Decide which things you are, and aren’t willing to commit to.

- Make decisions that align with your goals. Including what kind of lifestyle you want, and how you want to spend your time and dollars.

Keep reading and we’ll guide you through it.

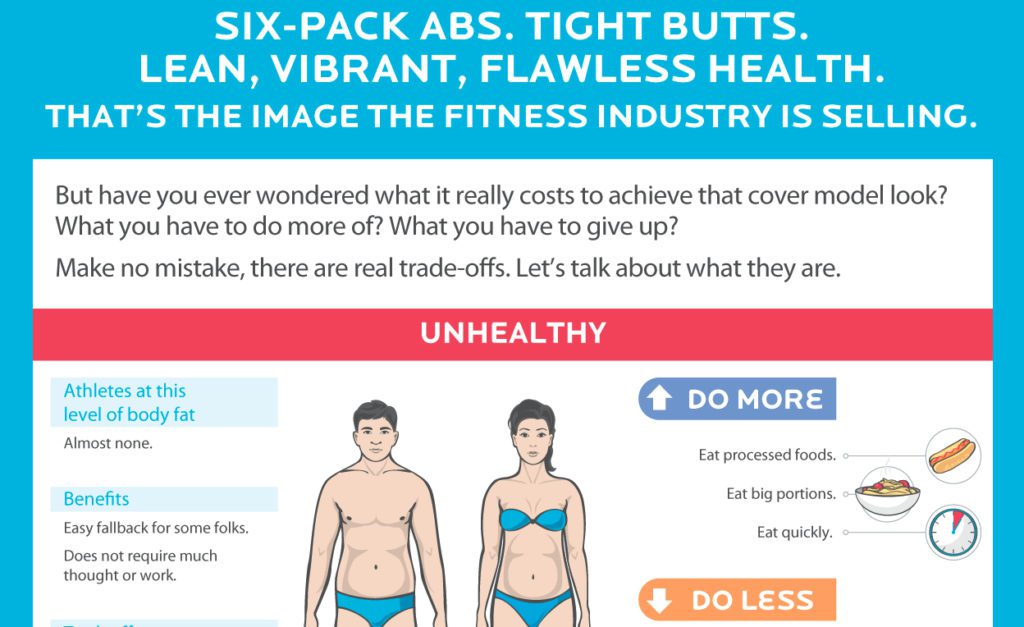

The benefits—and tradeoffs—of a healthy lifestyle

Putting effort towards your health is great. But efforts come with tradeoffs.

Here’s a look at both the efforts, and the tradeoffs, to achieve the health you want for yourself.

Take The Longevity Assessment

How do your health and longevity efforts stack up? What can you do to make the biggest difference? Take The Longevity Assessment and find out! To begin, simply click “Get started” below.

A deeper look: The most effective health behaviors (and their optimal dose)

If you want to reduce your risk of chronic disease, and generally stay healthier for longer, what should you do?

As we said earlier, the issue isn’t that we need some highly detailed, cutting-edge protocol. The basics work. The issue is that most people don’t do them.

For example, as shown in the image below, most people don’t get enough fruits and veggies, sleep, or exercise. And the number of people who do all these things on a regular basis (while also avoiding tobacco and minimizing alcohol) is extremely low: likely a fraction of a percent.

Finally, let’s take a closer look at what these basics are, and the “sweet spot” of effort versus reward.

Foundational Health Behavior #1: Exercise regularly

All health experts agree: Moving your body is important.

Yes, exercise will help you stay lean, and improve mood, energy, and function, but it will also help you stay alive (and healthier) for longer.

In fact, a study of Harvard alumni found that any amount of physical activity reduces the risk of death from any cause. Exercise extended lifespan regardless of body weight, blood pressure, smoking habits, or genetic predisposition.7

Another study of 272,550 older adults found engaging in even low amounts of physical activity significantly decreased risk of death from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and all causes.8

Specifically, steep risk declines happened when accumulating at least 7.5 MET-hours* of activity per week. The greatest increase in benefits came from achieving 7.5 to 15 MET hours. Increasing activity beyond that further decreases risk, but at a continually lower rate, as the graph below shows.

*MET-hours (Metabolic Equivalent Hours) measures the energy cost of activity, based on duration and intensity. Some examples: 2 hours of resting = ~2 MET-hours; 2 hours of moderate-intensity aerobic activity = ~8 MET-hours; 2 hours of moderate resistance training = ~7 MET-hours.

Increasing the intensity of exercise is an efficient way to rack up MET-hours, but plain old walking counts too: In a study of 28,000 adults, every 1,000 daily step increase was associated with a 12 percent lower risk of death. (This association began at 2,500 steps and continued up to 17,000 steps.)9

(Cool factoid: For folks concerned with dementia in particular, one study showed that getting just 3,826 steps per day was associated with a 25 percent reduced risk of dementia—and getting 9,826 steps per day was associated with a 50 percent lower risk!10)

Ideally, cardiovascular activity is paired with resistance or weight-bearing exercise.

Resistance training supports health and longevity in various ways: it can help preserve valuable muscle mass, maintain mental sharpness, improve odds of surviving cancer, support metabolic health, and generally help you stay alive.11

Among older adults especially, falls are a leading cause of death.12 Resistance training can both prevent the risk of falls–because of improved balance and muscle stability13—as well as reduce the risk of serious injury–because of better bone density.14

A sedentary lifestyle does the opposite, increasing risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, cancer (breast, colon, colorectal, endometrial, and epithelial ovarian cancer), and all-cause mortality.15

In fact, two decades of sedentary lifestyle is associated with twice the risk of premature death compared to being physically active.16

▶ How much exercise should you do?

Standard exercise recommendations suggest:17

- 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic activity (or some combination of both), plus

- 2 sessions per week of resistance training, targeting most major muscle groups

Getting up to 300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity or 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (or some mix of both) as well as three resistance training sessions per week provides further benefits.

▶ Are people getting enough exercise?

Most people are not.

Only 24 percent meet the recommendations for both aerobic and resistance exercise. And fewer than 47 percent of American adults meet recommendations for aerobic physical activity.17

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

For the most part yes, but past a certain point, more effort delivers less benefit—and potentially more risk.

Overtraining (and/or under-recovering) can disrupt hormone levels, mess with sleep and mood, cause excess fatigue, chronically elevate your heart rate, cause injuries, and more.18 19 Extreme volumes of endurance exercise training may be detrimental for the heart, and increase risk of myocardial fibrosis, coronary artery calcification, and atrial fibrillation.20 21 22 23

So, the benefits of exercise exist on a U-shaped curve. (This is known as the “Extreme Exercise Hypothesis,”24 as seen in the image below.)

A “high” amount of exercise is good for you, but the “highest” amount possible probably isn’t. (Health benefits likely max out around 7-10 hours of cardio, and 3-4 resistance training sessions per week.)

We like what one study concluded: “If the mantra ‘exercise is medicine’ is embraced, underdosing and overdosing are possible.”25

Foundational Health Behavior #2: Eat a nourishing, nutrient-rich diet

Eating well doesn’t have to be complicated. There are a few key elements to nail down, and the rest is up to your own personal preferences and needs.

We suggest focusing on three nutrition fundamentals.

Nutritional key #1: Eat more whole and minimally-processed foods

Whole and minimally-processed foods are naturally nutrient rich—complete with fiber, healthy fats, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals—and far less calorie-dense than highly- or ultra-processed foods (UPFs). They also have less sugar, sodium, and trans fats—the latter which is directly linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, complications during pregnancy, colon cancer, diabetes, obesity, and allergy.26 27 28

These qualities contribute to their many health benefits; Diets rich in whole or minimally-processed foods are associated with lower rates of depression,29 30 31 heart disease,32 type 2 diabetes,33 cancer,34 and improved longevity.35

The largest study on processed foods—which included almost 10 million participants—found UPFs are linked to 32 harmful effects, including type 2 diabetes, mental health disorders, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality.36

Another study found that a higher consumption of ultra-processed foods (four or more servings daily) was associated with a 62 percent increased risk of all-cause mortality. (For each additional serving of ultra-processed food, all-cause mortality increased by 18 percent.)37

Not that you need to be plucking tomatoes straight off the vine.

Eating a minimally processed food diet is more about overall dietary patterns—and moving along the continuum of improvement—rather than rigidly avoiding all forms of processing.

▶ How many minimally-processed foods should you eat?

There currently aren’t any formal guidelines for the amount of minimally-processed foods to eat. In our experience coaching over 100,000 clients, we find people are most satisfied, and get significant health improvements, when 70 to 80 percent of their diet comes from whole or minimally-processed foods.

Any improvement counts though. If you’re currently eating very few whole and minimally processed foods, getting at least 50 percent of your diet from these foods would make a big difference to your health, energy, and longevity.

▶ Are people eating enough minimally-processed foods?

No.

Recent US data shows that Americans get about 28.5 percent of their calories from whole or minimally-processed foods, and 56 percent of their calories from highly- or ultra-processed foods.38

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

Not beyond a certain point.

If you want to, consuming up to 90 percent of calories from minimally-processed foods will truly maximize your benefits, but beyond that there are likely no further benefits.

Besides, some processed foods enhance health rather than detract from it. Think about the protein powder that helps you meet your protein requirements, the commercial salad dressing that helps you eat your vegetables, or the weekly brownie à la mode you share with your grandkid that brings joy to both of your lives.

(Read more: What you should know about minimally-processed foods vs. highly-processed foods)

Nutritional key #2: Eat five fruits and vegetables

You’ve heard it a million times. We’ll be the nag and say it again: Eat your fruits and veggies.

A massive study involving over 1.8 million people showed that eating more fruits and vegetables was significantly associated with a decreased risk of death—with the benefits plateauing at five servings a day. People who ate five servings a day had a 13 percent lower risk of death from any cause compared to people who ate two servings per day.39

Additionally, the consumption of fruits and vegetables very likely reduces the risk of hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke; probably reduces the risk of cancer; and possibly prevents weight gain.40

▶ How many fruits and vegetables should you eat?

A healthy target is five fist-sized servings of fruits and vegetables daily. (Generally, we recommend dividing that into three servings of veggies and two servings of fruit.)

For bonus points, try to eat a variety of colors.

The pigments in fruits and veggies come from various healthful nutrients (called phytochemicals or phytonutrients). Different colors mean different phytochemicals, giving you a diverse array of these beneficial compounds, which are likely responsible for a majority of the health benefits of fruits and vegetables.

(Read more: What the colors of fruits and vegetables mean)

▶ Are people eating enough fruits and vegetables?

No.

Americans only eat an average of 2.5 servings of produce (fruit and vegetables combined) per day.41

Only 12.2 percent of people meet fruit intake recommendations, and less—9.3 percent—meet vegetable intake recommendations.

A mere ten percent of Americans get a full five servings of fruits and vegetables combined per day.42

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

There are likely diminishing returns to eating more than the above suggestions.

In that massive study mentioned earlier that observed 1.8 million people, the life-extending benefits of fruits and veggies plateaued at five servings per day.39

In other words, higher intake (beyond two servings of fruit and three servings of vegetables) was not associated with additional disease risk reduction.

That said, there may be other benefits to eating more fruits and vegetables. For example, due to their fiber and water content, fruits and vegetables are filling yet low in calories, so they can support weight management—and they certainly aren’t going to harm your health.

Nutritional key #3: Eat enough protein

Protein is the most important macronutrient to get right, especially as we age.

Plant protein in particular is linked to a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and death from all causes.43 44 45

In terms of animal proteins, the results are more mixed. (That said, research on protein intake and mortality is generally based on observational studies that don’t give us clear ideas about cause and effect.) Generally, minimally processed forms of fish, poultry, and low-fat dairy are the best animal protein sources.

To minimize health risks such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, limit processed forms of red meat (like bacon, hot dogs, deli slices, and pepperoni sticks). Even unprocessed forms of red meat should likely be limited to about 18 oz (~4 to 5 palm-sized portions) or less per week.46 47 48

Nonetheless, regardless of the source, getting sufficient protein—at least 1.2 g of protein per kg of body weight—significantly reduces the risk for sarcopenia (muscle loss), frailty, and neuromuscular decline.49 50

Protein is also vital for maintaining and building muscle, keeping bones and soft tissues healthy, supporting immunity, and more. It’s also the most satiating macronutrient, and thus helpful for fat loss and/or body recompositioning.

▶ How much protein should you eat?

The current USDA recommendation for protein intake is at least 0.8 grams of protein per kg of body weight (0.35 g/lb). However, newer research suggests this is likely the absolute minimum amount, and only for relatively young sedentary individuals.

A better minimum intake for most is likely 1.2 g/kg (0.55 g/lb, or about 3 to 5 palm-sized portions of protein-rich foods), especially for older adults, as they’re at greater risk of muscle loss.

Protein intake for muscle growth and retention, and/or if performing resistance training or other vigorous exercise would be 1.6 to 2.2 g/kg (0.75-1 g/lb), or about 4 to 8 palm-sized portions of protein-rich foods.

▶ Are people eating enough protein?

That depends on how “enough” is defined.

Most adults eat at least 0.8 g/kg. However, up to 10 percent of young women and up to 46 percent of older adults don’t hit this mark.51 And, as noted, that recommendation is probably conservative compared to the ideal intake.

Protein is also especially critical for those on GLP-1 medications (Ozempic, Wegovy, Zepbound) to help prevent the muscle loss they can lead to. Aiming for at least 1.2 g/kg is vital for this population, especially if they are also older. (Getting closer to 1.6 g/kg is even better, if possible.)

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

Once you get up to 1.2 g/kg, not necessarily. That amount is likely adequate for most, especially sedentary folks.

If you’re trying to build muscle and strength or recover from vigorous exercise, or are taking GLP-1 medication for fat loss, striving towards 1.6 g/kg would help you achieve that goal more easily.

If you’re trying to maximize strength and muscle gains, and/or are doing lots of strenuous exercise, consuming 1.6-2.2 g/kg is optimal (with the highest end of that range maxing out all benefits).

What about supplements?

Supplements make up a large part of the discussion around aging, but in reality only play a small role when it comes to increasing health and longevity.

Using supplements (like a multivitamin, or doctor recommended vitamin D or iron) to prevent or correct deficiencies can be helpful for overall health well-being.

Then, there are other supplements that have reasonably strong track records and can help us meet nutritional needs (protein powder), improve performance (creatine), or potentially even slow aging (fish oil might slow biological aging by a small amount).52

However, the buzziest, trendiest supplements are often less proven.

For example, curcumin, spirulina, and ginger are often listed as supplements that might help with inflammation, a hallmark of aging. However, the research here is still early, and far from definitive.

There are also even less substantiated supplements that might modify other aspects of aging (resveratrol, NAD+, NAC), but the evidence is either very minimal or only in animal models.

Some supplements (especially herbal supplements) can even cause harm, like liver damage.53

If you want to give supplements a try, check for high-quality third-party seals of approval from organizations such as NSF.

Examine.com—an online database that provides independent research summaries and analyses on most popular supplements—is also an excellent resource to help you determine which supplements might actually be effective.

Regardless, talk to your healthcare provider before taking supplements, particularly if you take other medication.

Foundational Health Behavior #3: Get adequate sleep

Research shows that men who get enough quality sleep live almost five years longer than men who don’t, and women who get enough live two and a half years longer.54

Studies also show sleep is just as important for your heart health as exercise, whole foods, weight management, cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar control.55

Compared to 7 hours of sleep per day, a 1 hour decrease in sleep duration has been associated with an 11 percent increased risk of cardiovascular disease and a 9 percent increased risk of type 2 diabetes.56

Older adults who sleep less than 6 hours per night are at higher risk for dementia and cognitive decline than those who sleep 7 to 8 hours.57 (Deep sleep helps clear beta-amyloid plaques and wash out toxins from our brain, thought to be partially responsible for dementia.)

▶ How much sleep should you get?

Sleep experts agree that 7 to 9 hours a night on average—with at least 7 hours of sleep most nights of the week—is ideal for most.

However, the exact ideal hours may vary person to person.

Generally, the right amount of sleep for you is the amount that allows you to feel relatively refreshed shortly after waking up, and allows you to fall asleep relatively easily at bedtime, with relatively sustained energy throughout the day.

▶ Are people getting enough sleep?

About a third of US adults don’t meet the recommended amount of 7 to 9 hours of sleep per night.58

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

Not necessarily.

It seems that 7 to 9 hours of sleep a night is ideal in terms of health outcomes.56

Interestingly, longer sleep duration (over 9 hours per night on average) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and overall mortality.59 60 61

However, it’s not clear that these risks are caused by sleeping more. Just as likely, it may be other health problems (such as depression, sleep apnea, or heavy alcohol consumption) that lead to both longer sleep times and higher health risks.

(Read more: Transform your sleep—The scientific way to energize your body, sharpen your mind, and stop hitting snooze)

Foundational Health Behavior #4: Manage stress

When left unchecked for long periods of time (say, months or years without periods of recovery), stress can have negative effects on nearly every aspect of our health, as the below image shows.

Chronic stress—which tends to increase heart rate, blood pressure, and inflammation—increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.62 63 64 Additionally, long-term stress tends to worsen mental and emotional health, increasing the risk of anxiety and depression.65 It can also make people more likely to turn to substances like alcohol as an attempt to cope.66

That said… Not all stress is bad.

In fact, stress is a normal, natural, and even beneficial part of life; the right amount helps us feel motivated, purposeful, and engaged with life.

So, rather than avoiding or demonizing stress, it’s helpful to work with it, using it as an opportunity to develop healthy coping mechanisms, appropriate recovery strategies, and overall resilience.

And this doesn’t necessarily mean sitting on a cushion and meditating.

Stress management can include simple mindset shifts: Practicing self-compassion,67 having a growth mindset,68 and framing stress as a normal and even beneficial part of life69 have all been associated with better coping under stress.

Basic self-regulation skills also help. This involves noticing and naming what you’re feeling, having good control over your actions, and using a broad range of coping skills to help yourself process emotions and recover from stress. With these skills, you build self-awareness and the ability to handle challenges better, because you know how to calm yourself down after an activating event—regardless of how it went.

The below image offers a spectrum of more—small and big—ways to regulate stress.

▶ How much stress management should you engage in?

Think of stress management and recovery as a thing you do in proportion to the stress and demands of your life.

We often use the analogy of a jug: When stress drains your tank, stress management and recovery practices help fill it back up again.

And, as with all of the foundational health habits we’ve discussed, every little bit counts.

Whether you’re experiencing a little or a lot of stress in your life, even three to five minutes of purposeful recovery—doing deep breathing exercises, some journaling or gentle stretching, or just stepping outside to get some fresh air and listen to the birds—can help fill your tank.

▶ Are people doing enough to manage stress?

Probably not.

In the US, over a quarter of people report that most days, they’re so stressed they can’t function.70 In Canada, it’s similar: Just under a quarter of people say that most days in their life are either “quite a bit” or “extremely” stressful.71

Additionally, over a third of people say they don’t know where to start when it comes to managing their stress.72

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

Not necessarily.

The goal is to find your stress “sweet spot.” Because we all enjoy and tolerate different types and amounts of stress, how you feel is actually a pretty good indicator of whether stress is too low, too high, or “just right.”

As the image below shows, if you generally feel bored and purposeless, stress is likely too low; if you feel energized and engaged, stress is probably close to your “sweet spot”; and if you feel panicky or so overwhelmed you’ve started to feel hopeless, stress is likely too high.

While having a routine for stress management is a smart idea, there’s likely a point of diminishing returns here too. If you’re in that stress “sweet spot” (energized/engaged, not bored and not overwhelmed), then adding more stress reduction techniques might not help further—and may actually add stress by giving you yet another task to do.

Foundational Health Behavior #5: Stay socially connected

You might not think of social connection as a health imperative, but it is.

Not only is the social and emotional support associated with improved well-being, it’s also associated with reduced risk of premature death.73 74 When relationships are strong, people have a 50 percent increased likelihood of survival during any given time.75

In fact, one of the longest running studies—the Study of Adult Development out of Harvard Medical School, which has been tracking participants for over 87 years (and counting)—found that strong relationships were the biggest predictor of not only life satisfaction but longevity. (Relationships were more predictive of these outcomes than social class, wealth, IQ, or genetics.)76

No surprise, not having a social circle comes with its own distinct risks.

Social isolation and loneliness can increase a person’s risk for heart disease and stroke, type 2 diabetes, depression and anxiety, suicidality and self-harm, dementia, and earlier death.77 78

A frequently cited statistic highlights its profound impact:

The effect of social isolation on mortality is comparable to smoking up to 15 cigarettes per day79—surpassing even the risks associated with obesity and physical inactivity.80

▶ Are people getting enough social connection?

It seems many of us could use more friends.

About 1 in 3 adults report feeling lonely, and 1 in 4 report not having social and emotional support.77

Eight percent of adults say they have no close friends, 53 percent say they have between one and four close friends, and 38 percent report having five or more friends.81

▶ How much social connection should you aim for?

Generally speaking, research finds that people who have three to five close friends they regularly interact with (one to three times per week, in-person or via phone call) get the most social benefit.82 83 84 85

On average, interaction with a smaller group of people tends to provide more benefit than a large network of acquaintances.86

That said, individual needs vary. If you feel authentically connected to others, have a strong sense of belonging, and generally feel socially fulfilled, that’s what matters most.

▶ Is getting more than the recommended amount better?

Likely not. Some evidence suggests that excessive social engagement (daily or multiple times daily) actually might increase mortality risk.87 That’s probably because over-socializing can increase mental, emotional, and physical fatigue,88 and often this level of socialization includes alcohol or other potentially risky behaviors.

Additionally, it can take away time and energy that could be put towards other life-building and health-promoting behaviors (like work, exercise, or sleep).

The takeaway? Strive for socializing that brings value to your life. No need to add so much that you wind up exhausted, or unable to keep up with other priorities.

Foundational Health Behavior #6: Minimize known harms

Minimizing activities we know to be harmful is a key part of looking after your long-term health, yet it can be easy to overlook these things. (Maybe because we’d rather keep doing them.)

Two of the biggest culprits are smoking and drinking alcohol.

Harm Avoidance Key #1: Don’t Smoke

We all know smoking is bad for us. But smoking is still relatively common:

- In the US, 10.9 percent of adults smoke cigarettes, and 6.6 percent smoke e-cigarettes.89

- Globally, the trend is even higher: 22.3 percent of the world’s population use tobacco (36.7 percent of men and 7.8 percent of women).90

The WHO estimates more than 8 million people die prematurely yearly from tobacco use (with an additional 56,000 people dying annually from chewing tobacco).91 This makes tobacco a leading (i.e. top 3) risk factor for premature death and all-cause mortality.92

Smoking is also a risk factor for several chronic conditions, including coronary heart disease, stroke, emphysema, and cancer.93 (Globally, about a quarter of cancer deaths are attributed to smoking.90)

Harm avoidance key #2: Limit alcohol

At this point, the research is pretty clear: Alcohol has negative implications for your health, especially past a certain point of regular use.

Alcohol plays a causal role in 200+ diseases, particularly liver diseases, heart diseases, at least seven types of cancers, depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorders, and dementia.94 95

In 2019, 2.6 million deaths worldwide were attributable to alcohol consumption.96 For people in the 15-49 age range, alcohol is the leading risk factor for death, with 3.8 percent of female deaths and 12.2 percent of male deaths attributable to alcohol use.97

▶ How much alcohol is “safe” to drink?

US guidance on alcohol suggests keeping intake at moderate levels, or less.98

A moderate intake means:

- Two drinks or less per day for men (14 or less per week), with no more than 4 at a single sitting

- One drink or less per day for women (7 or less per week), with no more than 3 at a single sitting

Importantly, a drink is defined as containing 14 grams (about 0.6 fluid ounces) of pure ethanol, which equates to:

- 12 ounces of regular beer (5% alcohol by volume)

- 5 ounces of table wine (12% alcohol by volume)

- 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (40% alcohol by volume)

▶ Are people limiting their alcohol enough?

In the US, people tend to drink more than the recommended guidelines.

In 2021, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism reported that the average American aged 21 or older consumed 2.51 gallons of pure alcohol over the course of a year—equivalent to about 10 standard drinks/week.99 However, research suggests surveys typically underestimate consumption by 40 to 50 percent.100 Further, other research shows that the heavier a person drinks, the more significantly they’re likely to underestimate and/or underreport their drinking.101

All that to say, the average American is likely having more (or even far more) than 10 drinks per week.

Add to that:

- In 2016, 36.4 percent of Americans (age 15+) said they had at least one episode of binge drinking (6+ drinks in one session) in the last month102

- About 7 percent of the world’s population aged 15+ years have an alcohol use disorder96

- Alcohol-related deaths have been rising: in the last five years, alcohol-induced deaths have increased by 26 percent103

▶ Is more abstinence from alcohol better?

In 2023, the WHO released a statement saying no amount of alcohol is “safe.”104 This interpretation is still debated, and data continues to emerge.

Here’s our take: An abstinence-only policy is likely a failed policy for many. Rather, we want people to be informed so they can make intentional decisions.

To be clear, alcohol is not beneficial for physical health; it’s a known human carcinogen. However, while alcohol does increase health risks, risk does not rise in a linear fashion with intake. Meaning, small doses are unlikely to have a significant impact on your health. But when you drink more heavily, the risks rise exponentially.105

Drinking heavily can mean either:

- Having more than 7 drinks in a week for a woman, or more than 14 drinks in a week for a man, or

- Having 4 or more drinks in one sitting for a woman, or 5 or more drinks in one sitting for a man (binge drinking).

(Reminder: A single drink refers to those definitions mentioned previously. Pints of beer, and heavily poured wine glasses and cocktails are more than single servings… Just because it fits in a single glass doesn’t mean it counts as “one” drink.)

Ultimately, it’s about finding the level of risk you’re willing to tolerate relative to whatever benefits you feel alcohol provides you.

Our general recommendations:

- If you’re otherwise healthy and have no other alcohol-related risk factors, limit drinking to moderate levels or less

- If you’re otherwise healthy but have one or two alcohol-related risk factors (such as breast cancer history), limit drinking to light levels (1 to 3 or 4 drinks per week) with occasional moderate intakes on special occasions, or less

- If you have several alcohol-related risk factors (such as breast cancer history, family history of alcoholism, or contraindicated medications) abstain from alcohol entirely

Foundational Health Behavior #7: Do Basic Preventive Health Measures

In all the chatter about longevity optimization, it can be easy to forget about all the boring—but no less important—things that help you stay safe and healthy throughout your life.

These include things like:

- Getting regular check-ups, or seeing your doctor or healthcare provider if questions or concerns arise

- Getting recommended bloodwork, screenings, and vaccines

- Getting and keeping blood cholesterol, sugar, and pressure in recommended ranges as early as possible

- Regularly seeing your dentist, and regularly brushing and flossing

- Practicing safer sex

- Seeing medical specialists as recommended or appropriate (OBGYN, optometrist, ENT, dermatologist, etc.)

- Wearing seatbelts (Buckling up in the front seat reduces risk of fatal injury by 45 percent!106)

- Wearing a helmet when cycling, skateboarding, or motorbiking

- Regularly wearing sunscreen (Used appropriately, sunscreen decreases risk of skin cancers by 40 to 50 percent107 108)

- Protecting your hearing (Untreated hearing loss increases risks for depression, social isolation,109 110 cognitive decline,111 dementia,112 113 and falls114 115)

… And generally using common sense. (As in, avoid the “hold my beer” type stuff.)

Basic health maintenance and risk avoidance practices matter—a lot.

Notably, we can’t control every element of our environment. Some factors influencing our health are more structural and systemic, woven into the fabric of our societies.

These are called social determinants of health, and include poverty, racism, homophobia, lack of accommodation for disabilities, and displacement (as in the case of refugees). For some folks, doing the above protective behaviors—like visiting the family doctor, getting glasses, going to the dentist, or even walking safely down the street—will be harder, sometimes near impossible.

This isn’t meant to be a throwaway line that diminishes the difficult reality for so many people, but rather a gritty, realistic mantra: Do the best you can with what you’ve got.

▶ How much preventative health care do you need to do?

Generally speaking, aim to be consistent with the habits you know you “should” do.

You know the drill: Brush and floss daily; wear your helmet every time you ride a bike; wear your seatbelt every time you drive; put on sunscreen when you go out into the midday sun; don’t regularly blast your music at full volume; and so on.

And if you have lingering things on your “I should really do that” list (like getting that weird mole checked out, or that bloodwork done), go do it.

▶ Are people practicing enough basic preventative health measures?

We’ve offered a long-ish list of basic health practices that can protect health, so we won’t go into each in-depth.

That said, when looking at the above list, it’s probably fair to say most people will notice a few behaviors they might practice more consistently.

For example, while most of us are really consistent with our seat belts (usage is close to 92 percent!116), many of us could break out the floss more often (only 32 percent of Americans floss daily117).

And, research shows that only about half of cyclists and motorcyclists wear helmets when riding118 119 120 (and use is even lower among skateboarders and rollerbladers121).

Hearing loss is the number one modifiable risk factor for dementia,122 so make sure you also follow the “60/60 rule” if you like to pump up the tunes on your headphones: Listen at 60 percent of your device’s maximum volume for 60 minutes, then take a break. (And wear earplugs when you mow the lawn!)

▶ Are more preventative measures better?

Once again, there’s likely a law of diminishing returns when it comes to preventative health measures, just like everything else.

The point isn’t to become obsessed with eliminating all possible risks at every turn.

Rather, it’s that reasonable efforts towards protecting your health do count, and they‘re immeasurably more important for overall health than the latest optimization fads.

Bonus Foundational Health Behavior: Foster a sense of purpose and meaning

Research consistently shows that having a strong sense of purpose and meaning for our life improves our health, overall well-being, and longevity too.123

A sense of purpose seems to help people live longer, even when controlling for other markers of psychological well-being.

There’s something uniquely beneficial about having a strong purpose that’s different from, say, being happy.

Having a strong sense of purpose can mean many things, but it generally indicates that you have goals, and an aim in life.

This purpose can be many things:

- Helping others

- Being connected to family and/or close friends

- Being a key part of a community

- Enjoying a hobby

- Learning new skills

Having purpose may help with longevity for a few reasons:

It makes you more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors, such as getting enough sleep and eating more fruits and vegetables.123

It also tends to improve mental health. For example, one study showed that people with the strongest sense of purpose had a 43 percent reduced risk of depression.123

Finally, it may simply help people live longer because it makes you want to live longer. When people have a sense of purpose, they often want to live longer, healthier lives, so they can fulfill that purpose to its fullest. And while wanting to live won’t make it so, it certainly doesn’t hurt.

Still thinking about optimizing? Consider these additional tradeoffs

We hope it’s clear by now: You can take yourself really far with some solid basics (that will themselves take some decent time and effort!).

But, if you want to go even further, your effort might have to increase exponentially, just as those gains become less certain, and more marginal.

Here’s what to keep in mind.

First, it takes a lot of time (and money) to optimize.

Let’s compare the time and financial investment of two imaginary people.

The first person is what you might call a “healthy” or “medium effort” person. They’re someone who is pretty consistently meeting all of the above recommendations.

The second person is what you might call an “optimizer.” They do all the above recommendations, but to the max, and many of the fringe recommendations often discussed on health-related podcasts and books.

How much time and money might each of these people invest in their health efforts on a weekly basis? Here’s what that might look like.

On top of that, there are “optimizing” behaviors and assessments that might be performed less often—say, monthly, seasonally, annually, or even every few years. Of course, these practices will still require time and money, so even though they’re less frequent, they still have to be accounted for.

Here are some examples of those kinds of products, therapies, and tests:

- Dietary supplements (vitamin, mineral, and/or herbal supplements; “superfoods”; fish oil; probiotics, resveratrol, NAD+, NAC, curcumin, & more)

- Bloodwork testing (for advanced lipid testing, inflammatory markers, hormone levels, and nutrient status)

- IV therapy (for hydration, vitamins, glutathione, or NAD+)

- Infrared sauna sessions

- Plasma transfusions

- Gene therapy

- Stem cell therapy

- Medical tourism and therapeutics retreats

- Full-body MRIs

- Genetic testing

- Concierge medical services

- And more…

Though it’s hard to estimate the cost of these items, opting to do just a handful could easily cost an extra $10,000+ per year.

Overall, we’d estimate it takes at least three to four times the time, effort, and money to follow an “optimizer” type lifestyle, compared to a plain old “healthy” lifestyle.

As we’ve seen above, this 3-4x effort will likely translate to some extra benefits, but the medium-effort “healthy” lifestyle will likely get most people at least 80 percent of the results they’re after (such as improved lifespan, healthspan, and quality of life).

Besides, optimizing too much can negatively impact your well-being and quality of life.

The harder and more extreme someone’s fitness or health regime, the harder they typically fall off the wagon. So, taking on too much can actually put you more at risk of quitting the foundational health behaviors we mentioned earlier.

Even if you stick with it, over-focusing on health and longevity will almost certainly interfere with your ability to enjoy a full, well-rounded, meaningful life.

For example, if you get too focused on physical health, you may find other aspects of your deep health and overall wellbeing suffer, such as your relational, existential, mental, and emotional health.

Take this a step further, and “optimizing” can tip over into obsession. Sometimes, under the surface of “I just really care about my health” is disordered eating, orthorexia, or another mental health condition.

This, to us, is the heart of things: It’s important to not only stay relatively healthy, but also to enjoy your life while you’re living it.

In fact, enjoying your life isn’t separate from good health. It’s part of it.

What to do next

1. Clarify your goals.

Take a step back and consider what you really want most for yourself.

What kind of life do you want to have?

How important is it to maximize your healthspan and lifespan, and how does that line up with your other priorities?

2. Consider the tradeoffs.

Given what you want most for yourself, and the resources you have available, what’s realistic for you?

How much time, money, and effort are you willing to put in to achieve health and lifespan goals?

What are you prepared to give up? What aren’t you prepared to give up?

3. When looking to make improvements, start with the basics first.

Review the foundational health behaviors in this article. How many of them are you already doing? Consistently?

If you’re covering most of the basics, you might not need to do more. (Give yourself a pat on the back. You’re already elite!)

Or, maybe there’s some room for improvement and you’d like to step it up a bit. Great! For the vast majority of people, improving any of these behaviors will deliver real, tangible results. Start with these, before chasing faddish, fringe, “super-optimal” stuff.

4. Tune out the noise.

Those people you hear on podcasts or social media aren’t the experts on you and your life.

You get to decide what you want, and how to go about getting it.

Be honest with yourself, and make choices aligned with what matters most to you.

There’s plenty of advice out there, but remember: It’s your life. You get to make decisions that work for you.

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

You can help people build sustainable nutrition and lifestyle habits that will significantly improve their physical and mental health—while you make a great living doing what you love. We'll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification. (You can enroll now at a big discount.)

Share